These days, it’s hard to go even a day without reading about the climate crisis.

And it’s no surprise why. With the knowledge that there might only be 11 years left to stop the irreversible effects of climate change, the daily alarm bells are a testament to the urgency of the situation. Countries all over the world have swung into action, with Singapore recently pledging $100 billion to tackle the problem.

But this is not fast enough for young people all over the world, who will bear the brunt of the effects of climate change in the future. Fuelled by the belief that authorities and corporations have failed to tackle the climate crisis adequately, they have taken things into their own hands, staging strikes and protests to advocate for stronger policies towards climate change.

Even Teen Vogue, the US publication better known for delivering fashion advice and the latest tea on celebrities, recently published an article on how youths can take direct action at their schools, perhaps best capturing the zeitgeist of the moment.

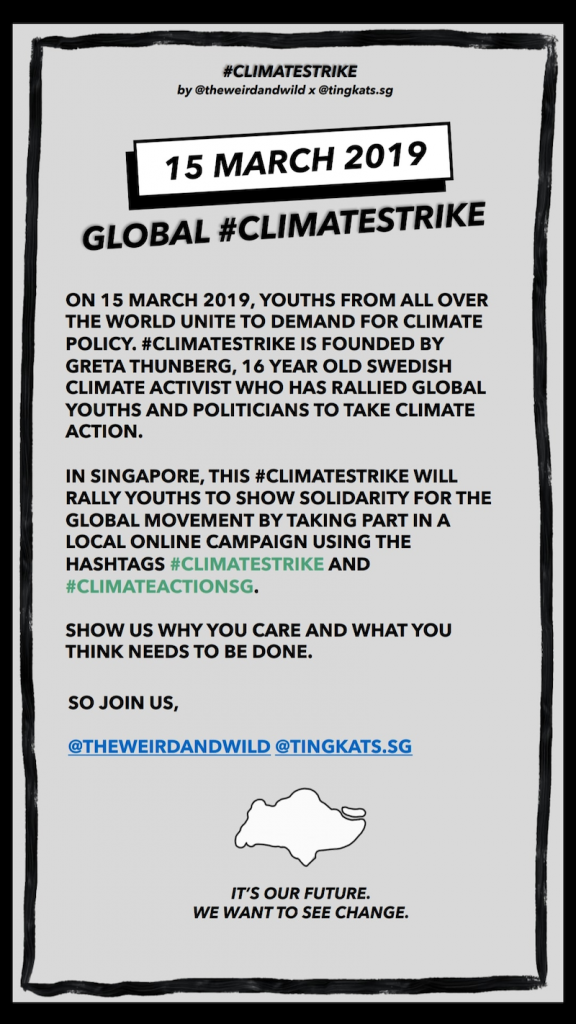

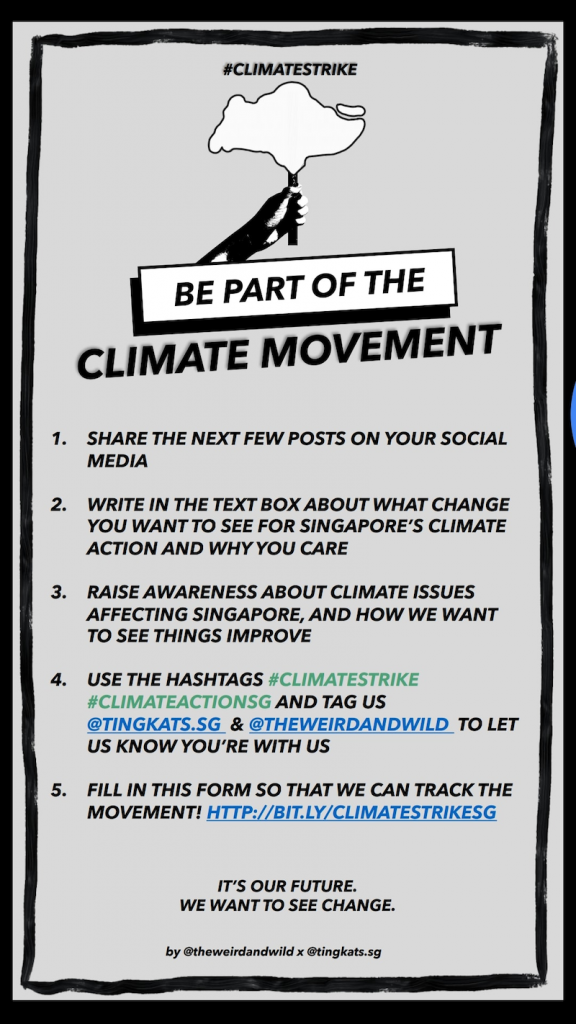

This fervour has spread amongst many youths in Singapore, albeit in a less contentious way and one more suited to our context. Conscious that strikes and protests are generally frowned upon in Singapore, two sustainability advocates, Pamela Low and Woo Qiyun, who run environmental Instagram accounts @tingkats.sg and @theweirdandwild, organised an “online climate strike” earlier this year, joining more than a million students worldwide who went on strike in solidarity with 16-year-old Greta Thunberg, one of the linchpins of the youth climate activist movement.

Surrounded by a constant deluge of messages about sustainability and whatnot, I’ve become a faithful supporter of such initiatives. I now carry around my metal straw, collapsible cup, reusable cutlery set, and tote bag on a daily basis, while signing all petitions calling for climate action and the end of capitalism. I’ve also started reading more about the climate crisis from authors like Naomi Klein, as a result of which I now feel ‘eco-anxious’.

But I didn’t write this article to virtue-signal about how ‘woke’ I am about the climate.

Rather, I’m asking: what more can be done?

Earlier this year, a journalist, Robin Hicks, noted that environmentalists in Singapore tend to be “upper-middle class, westernised Chinese-Singaporean women”. Sustainable products and food also tend to be more expensive than the norm, potentially disincentivising those who want to support sustainability-related efforts but cannot afford to do so. Why buy a bamboo straw when I can get a plastic one for free every time I buy a drink? Why eat a $20 Impossible Burger when I can get a $3.50 chicken rice?

A general observation is that environmental activists tend to be university-educated or educated overseas, and are English-speaking. In that sense, might the movement be somewhat unconsciously giving off an ‘elite’ vibe? Is it an echo chamber, in the sense that sustainability is the preserve of the middle-class and above, who are somewhat privileged and able to care about environmental issues?

To test this hypothesis, I went down to Youth X Sustainability, an event bringing together youths passionate about sustainability and featuring a panel discussion of several prominent youth climate activists. If there was an event that could represent the heart of the movement, this would be it.

Upon stepping into the room, I was pleasantly surprised to find more guys than I had expected. Still, the majority of the panel were university-educated (with 4 coming from NUS/Yale-NUS) or from an elite school, and the audience, from what I observed from a breakout session of introductions, appeared likewise.

Yet, I wondered: were they just preaching to the choir? Surely everyone in the room were already aware of all these?

As the floor opened for questions, I readied myself to burst the kumbaya bubble and ask about what plans they had to reach out to people outside the movement. But the questions from the audience thoroughly surprised me:

“Our current solutions to sustainable energy, sustainable food, sustainable consumer wear is … not available to consumers at a low price … how can we improve this, especially in Singapore?”

“How can we make environmental activism more accessible? So like making sustainability more accessible not just in terms of a consumer, but as an activist that cares about the issue. I think it’s safe to say that all of us here are at a certain amount of privilege to be able to come here on a Saturday, but what about those who have to work or don’t have the time or mental capacity to think about these issues?”

“In your work on what you know is being done in the sustainability field, what has gone wrong and what can be done better?”

It’s safe to say that these were not the kind of questions I had expected to be asked, and they were better than any that I had prepared. To the speakers’ credit, they responded frankly and thoughtfully.

“I think there really is an elitist sort of tendency in environmentalism. I think it tends to be educated and privileged people who can access this space,” said Aidan Mock, a senior year student at Yale-NUS majoring in Environmental Studies.

“There is a tendency among sustainability circles to focus on solutions that are only available to people who have the means to afford certain things … I think the solution to that, in my opinion, is that it has to be an institutional priority; that means when we’re thinking about reforming our systems of consumption and production, we also have to think about access … we have to ensure climate justice is a part of that transition.”

Aidan also talked about a list of five things for environmentalists to take note, which I found tremendously helpful and reproduce below non-verbatim:

1. Language: What language are you communicating in when doing outreach, and who does it exclude from your discussions? Environmental communication tends to be in English, excluding communities where that may not be their primary language.

2. Time: Who can afford to take time out on a Saturday afternoon to come down? What about weekday evenings? How can events be held at different times to draw in different varieties of people?

3. Location: Environmental events are often held in spaces where regular people may not have access to, or require a lot of time to travel to. Can events be held in locations that are more accessible?

4. Task: Can there be a variety of tasks that are scalable for people with different abilities to commit to?

5. Topic: Talking about ‘carbon emissions’ or ‘climate mitigation’ are rather abstract topics that might not resonate with society at large. Can other topics like dengue fever, which is also a related concern due to climate change affecting the breeding patterns of mosquitos, be looked at to draw in people who do not traditionally engage with the environmental movement?

She also added: “Something that I think is very scary is that when you come to tell people who don’t know anything about this topic about stuff like ‘carbon emissions’, who will know how much [carbon tax] to charge … when you tell someone that we charge $5/ton, to them it’s like, ‘what does that mean?’”

“I think that we’ve created a barrier to get people to start on this journey, so in order to be more accessible, we need to start on the basics of what we really care about, like smelling nice, looking good, stuff like that.”

After the event, I caught up with Tammy Gan, a 21-year-old youth environmental advocate and organiser of the event, asking her about her thoughts about the discussion on the inclusivity of the movement.

While pleased that the event achieved her goal of creating a space for the movement to discuss issues candidly, she noted that the audience itself was not as diverse as she had liked it to be, and also agreed that the typical environmentalist tended to be middle-to-upper class, Chinese or Caucasian, and that it was not uncommon for panels about environmentalism to be made out of purely Chinese girls.

On her Instagram account, @lilearthgirl, Tammy spreads awareness on environmental issues. Speaking about a conversation she had with one of her Instagram followers being uncomfortable speaking about her views on the climate because she didn’t have a role model that looked like her, she added: “We need to recognise that there are many genders, races, and classes in this environmental fight, and we need to diversify in terms of representation and appearances … we have to visibly see people who are not of the same ‘type’ on the panel or heading events.”

She also talked about her plans for the future of empowering other people to host similar events: “It’s about giving a voice to people who are not of the majority…so really being like ‘here’s how I did it, now you do it’, instead of me doing it, and having you on the panel.”

“It’s really about using your position of privilege to put people in less privileged positions in power.”

Taking into consideration Aidan’s point on ‘location’, I probed him further: much of climate activism has been done on social media and online spaces, which is understandable as those are the most effective ways to reach the youth; what more can be done to reach people outside of your online social circles or not in these spaces?

“I’m thinking [there can be] community spaces and community events that a diversity of people can access. For example, could we put up booths at pasar malams to engage with people who don’t normally engage in these sorts of spaces? Or hawker centres, stuff like that,” he replied.

“You’d also have to change your messaging, it wouldn’t be primarily in English, especially for hawker centres.”

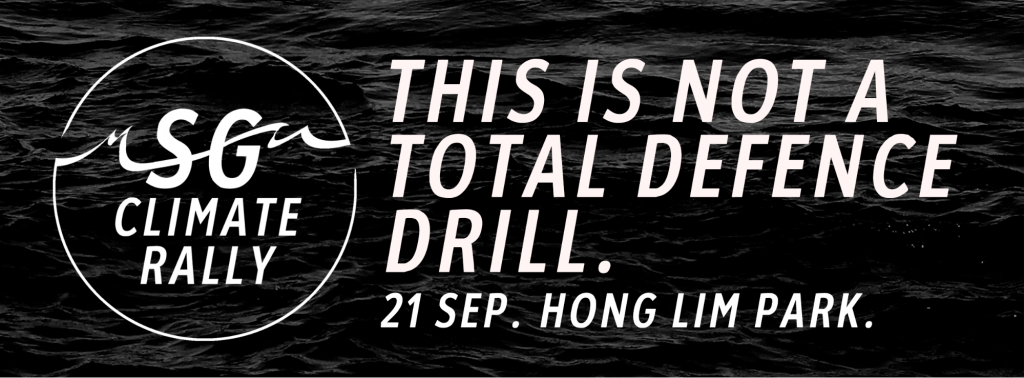

Putting his own advice into action, Aidan is also part of the group of youths organising the SG Climate Rally, taking climate activism offline as well. Inspired by Greta and held in conjunction with the Week for Future and Climate Justice, this will be Singapore’s first ever physical climate rally. The team will be spreading the news of the rally on social media as well as reaching out to environmental organisations and teachers in charge of environmental clubs in schools to encourage their students to show up.

They added, “More importantly, it provides a physical space for those who support political climate action to interact and feel empowered. Many people, young and old, have strong feelings about the environment and climate crisis but can’t discuss this in their daily lives—it’s a very sombre and distressing topic.”

“To these people, and to anyone who has ever wondered whether anyone cares about the climate catastrophe, this physical rally has a simple message: You are not alone.”

Although the topics being talked about at first were still rather ‘elite’ and privileged, I was heartened to see a self-awareness on the part of the youth in the audience and on the panel to make climate activism more accessible and inclusive.

It is perhaps no surprise that the youth climate movement in Singapore is rather insular for now. The movement first started overseas, and it is more likely that the ‘globalised’ youth in universities – who are more likely to be middle-to-upper class – would be the first to adopt it.

And it is still barely a year old. Given time and space, it is sure to become more accessible and inclusive to all and gain a mainstream audience. After all, issues like rising temperatures are something that everybody can care about.

It’s also imperative that the climate movement gains mainstream awareness so the focus of environmentalism can move beyond individual action and towards collective change. The oft-cited statistic is that 100 companies in the world are responsible for 71% of global emissions, and in Singapore, the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions come from very specific industries. While individuals and households can do their part, their actions can only go so far, and the burden of climate action must not fall exclusively on them.

Climate activists in Singapore have called for greater climate action like a higher carbon tax, greater focus on mitigating rather than adapting to climate change, and decarbonisation of the economy. While these are rather esoteric topics for now, approaching a larger audience with more accessible topics like dengue fever or rising temperatures would be a good start to attract more people to their cause.

Climate activists can then slowly educate their audience about their proposed policies, and urge them to raise it up at government dialogues and consultations, or even to their MPs. Political leaders are responsible to their constituents after all, so if there is a collective will for political leadership to enact such changes, they will respond accordingly.

However, building such collective will takes time. And sadly, with the climate crisis looming large, this is one movement that does not have time. Thankfully, youth climate activists appear to be on the right track. Although they may not have all the answers yet, they are asking the right questions and thinking long-term, seeking to build the movement instead of preaching to the converted.

Our house is on fire. Let’s make sure everyone has a stake in the fight to put it out.