All food delivery drivers in Singapore’s gig economy, namely the ones who deliver for Deliveroo, FoodPanda, and GrabFood, are considered self-employed independent contractors.

But few Singaporeans appreciate what the implications of this are, and what the future consequences might be, especially as Singapore heads into an economic downturn.

At Rice, we’ve covered various aspects of the Gig Economy, from an article about how Singapore’s food delivery isn’t sustainable, examining its steady encroachment on every aspect of Singapore life, as well as a review exploring the gig economy’s impact on families.

In this piece, we’re going to walk in the shoes of the food delivery heroes who are risking their lives during the CCB. Somehow, it always takes a crisis for us to truly appreciate what’s important, as well as the human stakes involved.

Let’s hope we don’t forget once things return to normal—whatever our post-Covid ‘normal’ ends up being.

In the Gig Economy, Freedom Isn’t Free

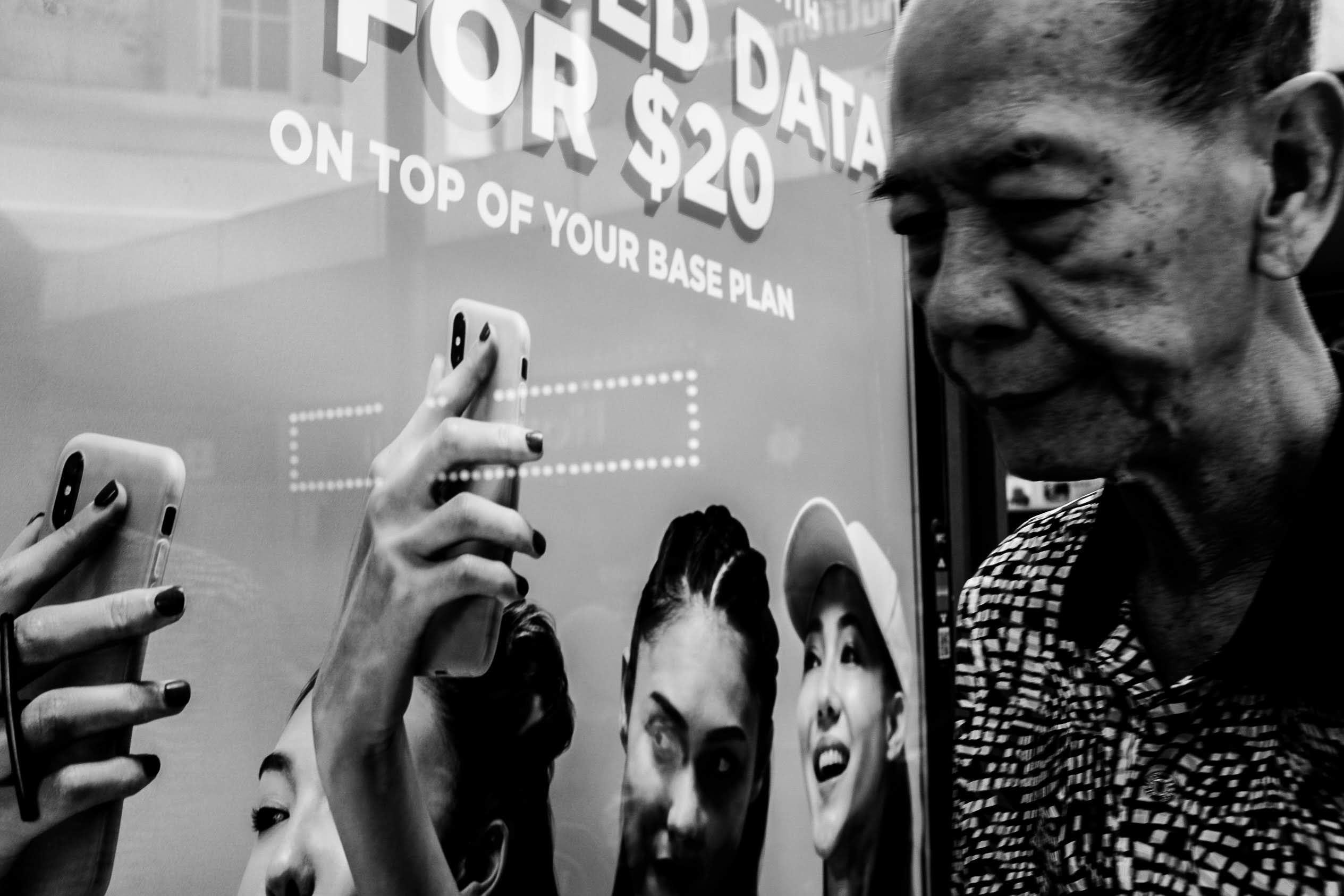

While the primary selling point of the gig economy is freedom to work when and where you want, this marketing campaign represents a fundamentally privileged and out-of-touch point of view.

Yes, for a certain group of Singaporeans with full time jobs and perhaps a pre-owned vehicle, occasionally picking up passengers and delivering food to hungry customers on the weekend can be a way to supplement their income—either to boost their discretionary budget or to help cover some bills.

But there are those who rely on the gig economy as one of the primary sources of their income. To them, working 5 to 7 days a week for 6-8 hours a day isn’t just an added bonus, but an urgent necessity. These are often people who have been left behind by the job market, who have had to piece together a living through a series of part-time jobs.

They could also be retirees whose CPF payouts are insufficient to cover their daily living expenses. These aging workers rely on the gig economy as a part-time income supplement, even as their energy flags and health deteriorates.

These are the vulnerable segments of the delivery economy I’ll be focusing on. Because frankly, if you’re competing for orders right now to earn some spending money for a Bali trip or a new smartphone, the CCB is really not the best time to be doing that.

During my research, I’ve stumbled across the hot takes from personal finance bloggers and FB commenters. The general sentiment is that gig economy drivers “should’ve known what they were getting into.” Rather than ‘complain’ about the raw deal they were getting, why didn’t they just walk away? Or better yet, be smarter about their careers and finances?

In other words, ‘get schooled’ and let them eat cake.

But over the years, I’ve learned that showing the reality behind people’s experiences and trying to walk in their shoes is more productive than playing Captain Hindsight.

A CCB Day in the Life for a GrabFood Cyclist / Youtuber in his 20s

Jonathan (not his real name), 25, is a GrabFood cyclist who delivers primarily to customers in the Tampines zone. He vlogs about his delivery experience using a mounted GoPro, and posts videos regularly to his Youtube channel, Guide to GrabFood.

Between his main trade as a hairstylist, which has been forced to shutter with the tighter circuit breaker measures, Jonathan drives part-time for GrabFood to help cover bills, as well as to keep his viewers informed about the situation on the ground.

To start off a Sunday at work during the CCB, Jonathan typically rides two 3-4 hour shifts centred around mealtimes. Since the CB began, the atmosphere on the streets has been eerie: malls have become ghost towns. Buses drive past carrying little to no passengers.

On balance, the number of orders Jonathan receives has been trending downward due to the increased competition for orders, as cabs and private-for-hire cars enter the delivery game. Drivers in some zones are reportedly getting only 5-7 orders on an eight hour workday. On average, delivery drivers earn about S$5-7 per order, which works out to S$25-50 per day.

One of Jonathan’s biggest challenges during the CCB is managing merchant delays. Wait times for merchants have increased due to the spike in food delivery demand and the entry of merchants who are new to the delivery platforms. One example was the AMK Hub Burger King episode following the shutdown of McDonalds.

By far, the most hated merchants among delivery drivers are the ones who wait to prepare orders only when the driver shows up. The customers at the other end aren’t aware of the situation, so when their orders arrive late, often by over an hour, they tend to shoot the messenger.

With customers, a common problem drivers face are those who forget (or refuse) to put their unit number in their address, then don’t pick up their phones when the delivery driver reaches their apartment. Jonathan is liable for any lost earnings due to either customer or merchant delay, most of which are out of his control.

Jonathan’s earnings are also heavily dependent on the everchanging platform incentives. “Improvements” that technology companies make to their apps, like stack orders, are often cost-saving measures that don’t benefit their delivery partners. Stack orders force drivers to make more trips for a lower flat rate. As an example, a normal order might be S$5 per single delivery, a stack order would be S$9 for three deliveries.

All of this casts doubt on the gig economy’s win-win proposition. The official marketing of these platforms casts their delivery drivers as ‘partners’, and yet these non-employee partners represent one of the biggest expense items on these tech companies’ profit/loss statements.

While GrabFood offers third party liability protection for its delivery partners (since June 2019) and basic insurance for accidents on the job, it is currently not mandatory by law for platform companies to do so.

The Unseen Burden on Older Delivery Drivers

In some ways, Jonathan is one of the lucky ones. He’s still young, fit, and likely has decades of earnings potential ahead of him.

The same can’t be said for older drivers who are close to or have already retired.

Last year, The Independent reported on a 72 year old retiree who drives for Grab to supplement his S$575 per month CPF payout, an amount that was insufficient to cover his monthly needs. Due to his status as a self-employed driver, this retiree was obligated to pay monthly Medisave top-ups, or else he risked his vehicle license being revoked.

Here’s the rub: the Medisave top-up amounted to S$595—more than one month of his CPF payout of S$575.

During the CCB, we’ve seen the frustration of older delivery drivers filter out onto social media.

Since delivery driver commissions are largely capped at flat rates based on supply and demand, drivers don’t participate in the upside of larger orders. And yet, when something (inevitably) goes wrong on the job, it’s the drivers who are left to bear most of the costs.

This not only highlights the lack of communication and support of these delivery platforms, but also shows how the game is rigged against the self-employed.

Appreciation for Delivery Drivers Won’t Put Food On Their Tables

In summary, the Singapore food delivery ecosystem consists of a ready supply of non-employees, whose non-employers are not legally accountable for worker compensation or protection. Whatever measures these companies choose to adopt, like providing third party liability insurance, is currently at their own discretion.

Similar to how deferring to dorm operators on migrant worker living conditions has led to our current crisis, relying on the goodwill of for-profit delivery platforms to take care of its drivers, especially as these startups struggle to cut costs, is both naive and shortsighted.

While the self employment stimulus announced by the Government, giving the self-employed S$9,000 in three installments during the Covid-19 period is a commendable step, it’s ultimately a temporary measure that doesn’t address the core legislative question:

Should gig economy delivery drivers be considered full time employees, self-employed contractors, or a new category of workers altogether? What sort of protections should they be afforded?

What Singapore can’t afford to do is split the difference, then refuse to take responsibility. In doing so, we’re leaving an entire group of Singaporeans in legal, financial and career limbo, one with lasting repercussions when they age out of the workforce.

And if the image of food delivery drivers riding through a ghost town as they risk their health to fulfill orders for hungry Singaporeans isn’t the ‘right time’ to raise awareness of their worker status, then frankly, there will never be a right time.

It would demonstrate that Singaporeans never actually cared as long as we got our food quick, cheap, and easy. Like our applause for our healthcare workers, it would make the praise for our ‘food delivery heroes’ sound hollow. Or worse, completely self-serving.

After the CB is lifted, it’s time to show that Singapore values concrete steps toward providing basic worker protections over empty signals of virtue.

Have an opinion or story on Singapore’s worker protections? Email us at community@ricemedia.co.