“啊,气死人!她不可以讲华语。我还以为她是华人 …“

It was a Tuesday. A Tuesday night, to be exact. I had rushed down from work to meet a beloved friend who had just flown in from Adelaide, South Australia. She had chosen the place for our dinner date because it needed to meet her religious and dietary requirements.

As I watched her fumble through the menu, dithering over whether to get an additional side of spring rolls, I heard the above comment quite audibly from behind me. It came from a Chinese waitress, who just a few minutes before had been smiling as she showed us to our tables. This smile had now flipped around, and she muttered under her breath as she tapped her pen impatiently against our order chit.

As soon as we decided, the waitress, now visibly irritated, snapped the menu shut and whisked our dinner orders to the kitchen before we could even thank her. I didn’t know if my friend had registered the tone in which that unwarranted comment was delivered because she definitely would not have understood it—she spoke Malay, not Mandarin.

Incredulous, I thought, for a restaurant that was supposed to be serving up Halal-certified dishes for Singapore’s Malay community.

And that was also the day my eyes were opened.

“I don’t want to always be told … that my experiences and emotions of feeling excluded in such spaces are not valid.”

“Ah, so frustrating! She can’t speak Mandarin. And I thought she was Chinese…”

Now, this is an opening sentence you can understand if you’re not familiar with Mandarin.

As of 2018, the Chinese comprise 76.1% of our city-state’s 5.7 million residents. Growing up, I didn’t feel the need to question my Singaporean identity when people who looked like me were well-represented in all areas of society. Ethnic Chinese wield social, economic, and political dominance in Singapore, and it has always been easy to take for granted that I could get whatever I wanted, wherever I wanted.

Ordering my favourite yong tau foo from that exclusively Chinese-speaking hawker stall? No problem. Dithering over whether go with a mind-numbingly spicy mala or chicken broth for my hotpot dinner? In my broken Mandarin, I could still wrangle an unenthused smile from the impatient staff, along with a few recommendations.

Yet such smooth, painless, and sometimes even pleasant experiences don’t apply to everyone.

When I spoke to my dinner date Sharifah* about my observations that night, it surprised me that it came as no surprise to her. While the 24-year-old Singaporean is Malay, she essentially looks Chinese. And growing up, it has greatly impacted how she navigates public spaces in Singapore.

While ruminating on my observations, she thinks aloud, “I’m not surprised anymore. My inability to speak Mandarin always incites that kind of reaction, and it’s not a one-off mistake.”

“Most people tend to assume I can converse easily in Mandarin based on my appearance. It happens a lot when I interact with Chinese-owned businesses in Singapore, but particularly more so in restaurants,” she adds.

“Their reactions differ each time it finally hits them that I’m not Chinese and I cannot reply to them in Mandarin. It changes in a snap second. Some look annoyed; some look bored. Most of the time, it’s usually the latter.”

When I ask if she ever feels welcome in such spaces, she replies, “No.”

Given the ethnic and cultural melting pot that is Singapore, along with the narratives of racial harmony and inclusion that are frequently peddled, it’s surprising to hear that any Singaporean can face such unpleasant experiences due solely to their race.

But before we break out in protest to argue, “Got such thing meh?” or, “Don’t anyhow say!”, we must understand the historical and social context of an experience such as Sharifah’s*.

Many Singaporeans have grown up knowing we can be boxed into at least one of the four categories: Chinese, Malay, Indian or Others (CMIO). Multiculturalism, we believe, underpins a racialised socio-economic framework in Singapore that is praised by many, and has become a social fact that we take for granted.

Yet if you peer closely at Singapore, you’ll start to observe that we are a nation with a “medley of people” who coexist harmoniously in the same space, yet don’t intermix with one another. Within these spaces, we have also formed clusters along racial divides—albeit on a more subtle and micro level.

As the majority, the ethnic Chinese have occupied most of these spaces. ‘Chinese-only’ spaces are largely unintentional by design, but very real. And according to Visakan Veerasamy, a 29-year-old who identifies as Tamil-Singaporean, it is a shared social reality for minorities in Singapore.

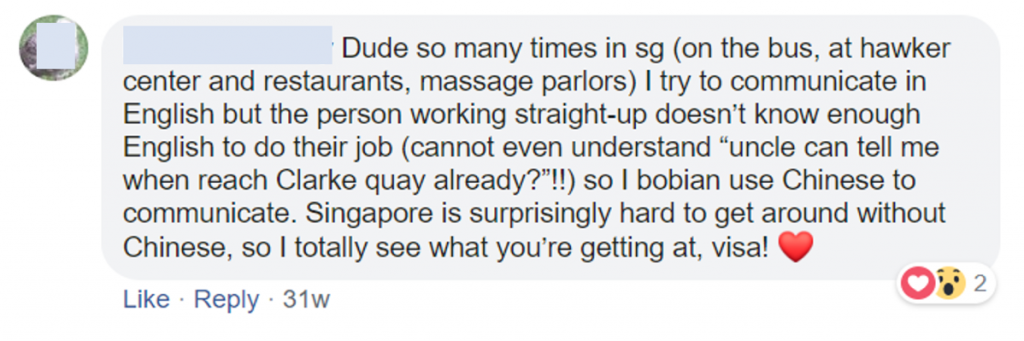

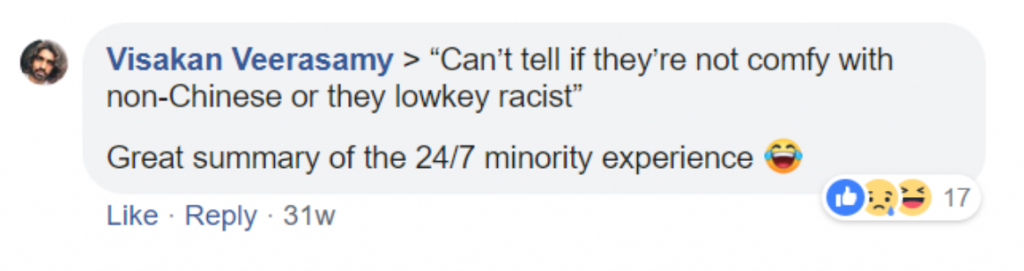

When I ask him to explain this further to me, he pulls up a Facebook post that he recently wrote. On 15 July 2018, he took to the social media platform to highlight his personal experiences with this particular social phenomenon. As a minority who doesn’t speak Mandarin, Visakan encounters no lack of ‘Chinese-only’ spaces in Singapore. And his personal recount of the associated negative experiences sparked a lively debate, garnering a mixed bag of responses.

“It was just an observation, not an accusation. Yet, I get the sense that people [in Singapore] are uncomfortable with such observations,” he muses.

“As a minority, the reality of ‘Chinese-only’ spaces in Singapore is much clearer to you. These include dim sum teahouses, hotpot restaurants and more where the staff and clientele are so overwhelmingly Chinese that non-Chinese folk feel intimidated to even approach [such a space].

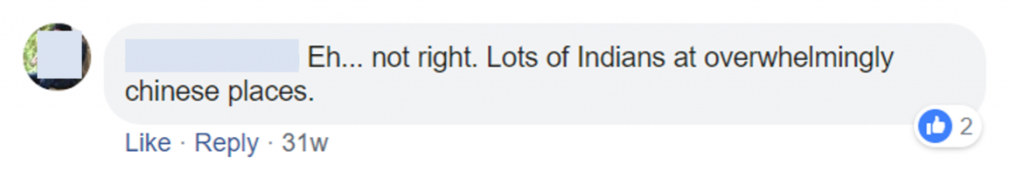

“The inverse doesn’t quite apply. You’ll often find Chinese folks at Malay and Indian food places.”

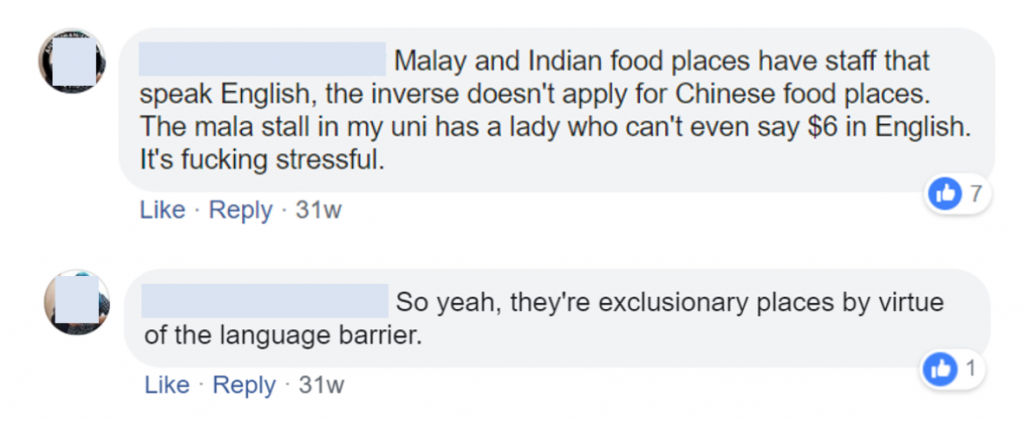

Some commenters were rational and supportive, acknowledging and sharing their own experiences—with a few even digging for potential solutions:

Some provided their perspective to help to spur healthy debate:

Finally, some echoed Visa and Sharifah’s respective sentiments:

To give credit where it’s due, I have observed many purportedly ‘Chinese-only’ food places that provide English menus; some even hire the odd English-speaking staff who scurry to your side once their colleagues wave them over upon realising you don’t speak Mandarin. Even dishes with the most complicated Chinese names would have an English translation written scraggily on a whiteboard hung high on the wall. While this allows Singapore’s minorities to navigate such ‘Chinese-only’ spaces with ease if they wish, many still feel alien and unwelcome.

“I may feel confident after looking through a Chinese menu with some English translations by the side,” Sharifah says, “But if I can’t order as quickly as they’d like in Mandarin, I can see the annoyance creeping into the waiting staff’s face.”

“I manage with some quick prodding at what I want in the menu and illegible mumbling. I can get by in such spaces, but it’s not a particularly pleasant experience.”

Encountering language barriers in Singapore can seem foreign to the best of us. After all, our country’s founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, made English the medium of instruction across races and society. Our three official languages of Singapore—Mandarin, Malay and Tamil—are taught as secondary languages.

Yet, it is these secondary languages that have helped shape these racially segregated spaces that unintentionally exclude minorities. It is also for this very reason that unlike Visakan, Sharifah would rather not talk about her negative experiences navigating ‘Chinese-only’ spaces in Singapore.

“I think the Chinese-ness of such spaces is exacerbated with the recent influx of foreign workers, particularly those from mainland China, who mostly work in the food and beverage industries,” she explains.

“I can understand that English is not their main language for communication, even if mine is. However, it’s very frustrating when they continue speaking in rapid-fire Mandarin even after you know that they’ve realised that you can’t understand them.

“It is these small things that add up and make me feel increasingly like an ‘other’ in such spaces, intentionally or otherwise.”

Visakan empathises with Sharifah’s experiences of being regarded as and feeling like an ‘other’ in ‘Chinese-only’ spaces. Unlike Sharifah, however, he doesn’t look one bit like the majority Chinese population. This, he says, is what exacerbates this feeling even further.

“Sometimes I just go into say, a Chinese restaurant, and eat in peace,” he explains.

“But once I go into such a space, I’m immediately regarded as an ‘other’. I know that it’s not intentional, and I know it’s mostly due to entrenched social norms in Singapore society. But it’s uncomfortable, and it’s not nice.

“However, when it comes to the majority Chinese not feeling comfortable with us entering such spaces of theirs…”

So, has there been much progress in the public discourse surrounding this issue? And how are Chinese-Singaporeans able to become genuine allies in pushing for such?

“I didn’t write that Facebook post to push this down everyone’s throat, expecting the wheels of a social and cultural revolution to begin in Singapore,” Visakan explains.

“As humans, we just don’t like being told what is wrong. We are quick to rush to defend or try to fix it. Yet, everyone doesn’t realise that the first and most important step towards pushing for progress on this particular issue is to listen and acknowledge that our experiences exist.”

When I mention Visakan’s response above to Sharifah, her voice picks up.

“Yes, listening! Listen, I’m not expecting any revolutionary social change to happen anytime soon—but I don’t want to always be told that ‘where got’ experiences such as mine, and that my experiences and emotions of feeling excluded in such spaces are not valid.”

Admittedly, I had to catch myself several times across the course of these interviews. It was tempting to speak out and defend what I thought was all Chinese people—why this was so, why that was so—and that as Chinese Singaporeans, we never mean to make them feel the way they do.

What both of them have shown me, however, is the importance of listening.

Listening empathetically is the hardest part, but once we do that, I think we can start to recognise and act on the microaggressions that minorities experience in such public spaces. The truth is that inclusiveness is an ongoing struggle, but we will never truly get there unless our eyes are opened to the fact that not everyone experiences life the way we do.

*Sharifah’s name has been changed to protect her privacy.