Let’s admit it: the world is in a bad place right now.

You can blame the sensationalist media or play the eternal optimist by looking at say, infant mortality rates over time (declining), or the number of people getting access to education and healthcare (rising), but these are arguably long term distractions to our short term problems.

When you’re being pelted by tear gas today, no statistic about a brighter tomorrow will keep you from crying.

Like everyone else in the world, Singaporeans watched the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. We watched the subsequent protests, riots, and looting on video. Closer to home, there’s the protests and violence playing out in Hong Kong. It’s easy to file these incidents away as something that happens ‘out there.’

To those people. In those places.

And we should thank our lucky stars that we get to live in the safety and comfort of Singapore.

For some, all narrative roads end here. A straight line is drawn from:

A. Difficult and complex problem, to

B. Easy and familiar conclusion

Yet whenever the criticism, fairly or unfairly, turns to any of Singapore’s problems, we are quick to leap to our own defense by pointing fingers elsewhere.

“Look at what’s happening in the U.S. and Hong Kong!” we scream. “Yes, Singapore has its problems, but no country’s perfect and everyone is doing their best!”

As if pointing to worse problems in the world absolves us of accountability for our own.

But here comes the punchline. Are you ready? In Singapore, this comment gets invoked the most often against a specific type of ‘complainer’:

“If you don’t like it here, why don’t you go back to where you came from?”

Staying Silent as an Asian Minority in America

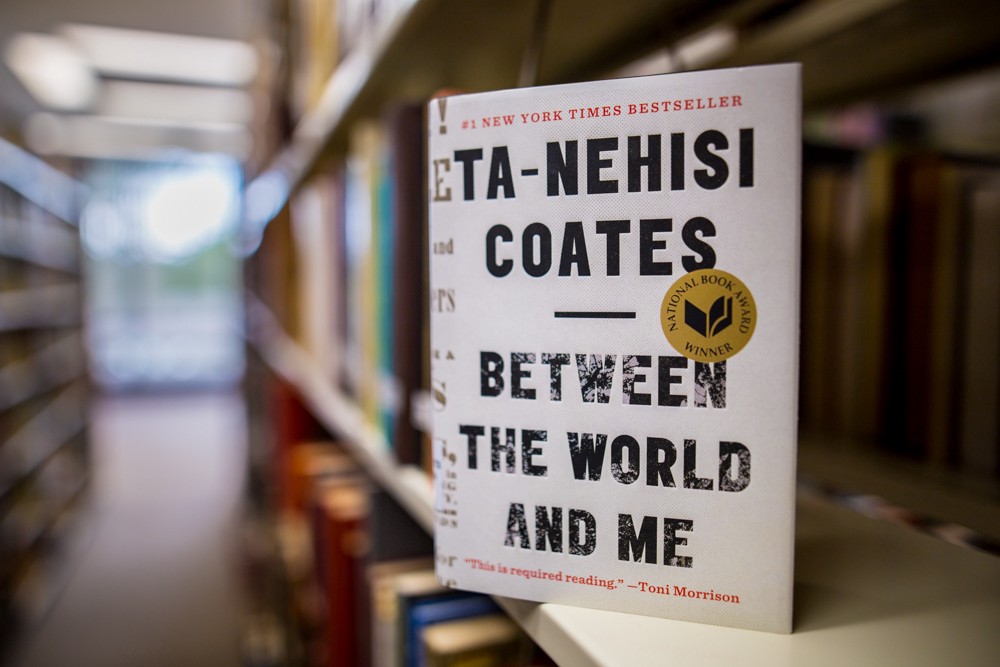

In 2016, I attended a technology conference in Boston, where the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of the bestselling novel, Between the World and Me, was a keynote speaker. While Coates wrote his book primarily as a lesson for the Black youth growing up in America, I was engrossed by the systematic challenges and despair he described through his personal stories.

Surprisingly, the book also did well with a largely white, affluent and educated readership. Presumably, many of them were members of the audience.

That day, Coates was scheduled to speak on the subject of his self-education growing up black in Baltimore during the ‘Age of Crack [Cocaine],’ which he describes vividly in his memoir The Beautiful Struggle. As a kid, Coates didn’t do well in school, having been churned through America’s public schools, an education system that fails Black Americans and Latinos at a disproportionate rate.

But Coates never ended up giving that talk.

Because this was the day following the election of Donald Trump. So he decided to go off-script, and speak from the heart.

For those interested in his full speech, you can watch it on Youtube here. But I was more interested in the reactions of the predominantly White and Asian audience around me (it’s a tech conference, after all).

Once it became clear to the audience that the speech would be about racism, sexism and politics, some people started heading for the exits. The ones who stayed looked either impatient, awkward or confused.

After the speech ended, the applause was noticeably muted. As everyone filed out of the auditorium, I listened in on the responses.

“This isn’t the right time or place for that kind of speech,” I heard someone say.

“Totally inappropriate. This is a business venue, not a political platform.”

For context, we were in Boston. Not exactly MAGA Trump country. Across the Charles River was Cambridge, home to the prestigious Harvard University and MIT, the twin bastions of American higher education.

The fact that these liberal elites, self-proclaimed ‘allies’ of minority groups, thought that there had to be a right time and place for Coates to speak out, sent me into a greater despair than any white supremacist rally I could ever attend.

But I kept silent. Because like Coates, I was also a minority in America. And though I would never compare my experience to that of the Black American, all minorities understand that to live in America is to live by a set of unspoken rules. To have a huge part of your identity defined by the assumptions of others.

For example, I’m Taiwanese-Canadian. But the majority of Americans wouldn’t know where Taiwan was. So I ended up being lumped into the category of “Asian,” with the Koreans, Filipinos, Chinese, Vietnamese etc.

And whatever prejudices the white majority had about ‘Asians,’ would also be tied to me.

In the workforce, this means that I am unassertive, lacking in leadership qualities, and passive. In Hollywood and the dating market, (the latter of which, because of my marriage, I was thankfully spared from) I was effeminate, sexually neutral, or simply ridiculous.

Some Asians in America were even held up as the ‘Model Minority.’ Within this unspoken social hierarchy, ‘the Asian’ was used as an example of the star pupil for all the Blacks and Latinos who were too ‘lazy’ and ‘didn’t apply themselves.’ Look at the Asian, they’d say. Someone who knows how to play their role. Who works hard, gets a good education, and most importantly, doesn’t make any trouble.

By contrast, most White Americans accept the privileges of being an ‘individual’ as a birthright. The backlash against the term White Privilege only proves the point that minorities are trying to make: it’s enraging to have to fight against other people’s definitions of you, simply because of the colour of your skin.

Moving into The Majority: Chinese Privilege in Singapore

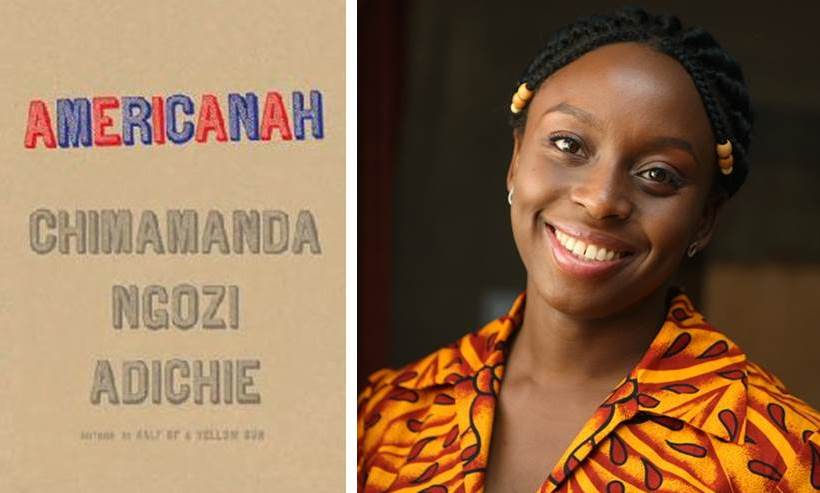

In her fictional, but semi-autobiographical novel Americanah, Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, wrote about how she didn’t realise she was ‘black’ until she moved from Nigeria to America. In Nigeria, everyone was black, and therefore, no one was. Just as nobody in Singapore identifies themselves as ‘yellow.’

In the book, Adichie describes how having spent most of her life as part of the majority race in Nigeria, she had to make a conscious effort to understand what Black Americans were going through. There was a mental hurdle she had to overcome in order to gain more empathy for her American brethren. Even though on the surface, they were all ‘Black.’

I experienced the same confusion when I moved to Singapore.

In Singapore, I suddenly found myself as part of the majority, and yet separated by my experience living as a minority in the U.S.

On one hand, when I introduced myself to Chinese aunties and uncles as Taiwanese, most of them understood what I meant, and placed this in its appropriate cultural and regional context.

This is because we shared the same language (Mandarin), ethnicity (Chinese), and cultural roots (Chinese culture).

On the other hand, I also attended a Singapore networking event in November 2019, held at a swanky bar overlooking MBS. My wife and I were considering moving to Singapore at the time, but we were worried about the difficulties of obtaining a work visa.

“You stand a better chance [of getting a visa] because at least you’re not Indian,” someone tried to reassure us.

“It’s not like you’re one of those Bangladeshis, who are driving local wages down,” said someone else.

These were highly educated, white-collar Singaporeans in positions of power. Their remarks were made casually. And they meant well. They may have thought that they were just explaining an honest reality to a pair of newcomers.

But I had been on the other side of those remarks before. And it begged the question: if I had been a member of another race or socioeconomic class, perhaps the ones mentioned in their offhand comments over cocktails, would they have confided in me to the same degree?

This was one of my first experiences with Chinese Privilege. When I started to suspect that I had gone from being ‘one of them’ to ‘one of us.’

What the Black Lives Matter Movement Can Teach Us About Singapore

In recent days, many prominent Singaporean influencers like Narelle Kheng and Anita Kapoor are coming out on social media in support of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Despite what the cynics say, this is heartening to see. In the modern era, it’s become impossible to separate authentic expression from the performance of it. Arguably, the backlash against the influencers also qualifies as performative ‘wokeness,’ that distracts us from the important issues at hand.

Because the discussion on injustice shouldn’t end in America with George Floyd.

Most inequalities aren’t going to be as stark as a policeman’s knee on a man’s neck. Some injustices are also closer to home.

So I’m not interested in the question “Does racism exist in Singapore?” This always devolves into tribalism and whatabout-ism, where there are no winners, and keyboard warriors end up wasting everyone’s time.

Does racism exist in Singapore? Yes, obviously. Racism exists wherever human beings exist. It’s just a matter of degree.

Instead, here are better questions to ask, precisely because they go beyond just race:

1. Which minority groups, if any, are being silenced by legislation and policy? Or by the cultural or socio-economic norms of the Singaporean majority?

2. Whose experiences and stories should we be actively seeking out? Even if it requires greater effort or inconvenience on our part?

3. What social issues make Singaporeans the most uncomfortable? Where does this discomfort stem from?

As responsible citizens, we all have to seek out the answers for ourselves.

For me personally, I see the role of a writer as someone who tries to reserve judgment, until I can hear out the voices that wouldn’t otherwise be heard, however painful or difficult that may be.

Because the powerful, by definition, will always have a platform to speak for themselves.

This article is sponsored by Storytel. You can start learning more about the ideological roots of the Black Lives Matter movement on Storytel, where the following titles are available in audiobook or e-book formats:

1. The Beautiful Struggle, by Ta-Nehisi Coates

2. Americanah, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

3. Speeches by Malcolm X: The Ultimate Collection, by Malcolm X

4. The Fire Is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America, by Nicholas Buccola

Or look for other titles on Race and Racism from this list curated by Storytel.

For RICE readers, click the banner below for a 30-day free trial.