Recently doxxing has taken hold of our social media landscape. Doxxing is the practice of researching, broadcasting and revealing personal information of an organisation or individual. It’s something that we Singaporeans love to do – when a man fails to pay his full petrol price, a cyclist and lorry driver cross turfs, when a male influencer cheats on and forces sexual advances on to women, and when an NUS undergraduate peeps and records a woman in the shower. Our lust for quick justice and emotional clickbait contributes to our burgeoning online mob mentalities.

The story, or stories, of perp Nicholas Lim and victim Monica Baey reached our news feeds and Instagram stories, dominating Singapore’s social algorithms and google trends. Following in tow to this viral story were the personal details of Nicholas and accompanying suggestions of new consequences that should follow.

What happened to Monica and many other girls are stories I hate hearing. I feel frustrated, angry, and disturbed that women in my country can be put in compromising positions, made to feel unsafe in supposedly safe spaces. In school, in a university and on the land of a country lauded to be safe, amongst citizens and peers alike.

I feel upset because men don’t seem to understand boundaries, they don’t seem to listen to women’s cries of disgust, and my own friends don’t seem disturbed by the act of voyeurism. These incidents draw the divisive line between male and female, those with power against the naked and disempowered. My heart aches as I glide through my social media feed, sighing at my peers’ inability to understand the gravity of this gendered crime. And I haven’t even got out of bed yet.

But something else tugs at my heart too. From online discourses, pitches for justice and calls for change emerge. Pitches and calls that are met with resistance, the question of what we should do. Should we ruin his girlfriend’s life for dating such a monster? Should his family suffer for raising such a deviant man? Should we order this person’s social death, rendering his image public enemy number 1? Almost always, the transgressor’s information gets spread throughout the depths of Singaporean internet – Facebook, Hardwarezone, and IG Stories aka the new credible source of journalism.

Doxxing presents itself as justice – but it is only a false sense of justice, undermining our ability to improve our institutions by blindly assuming they have our worst interests at heart. Doxxing ignores the systems in place that give due process to victims and perpetrators (citizens, humans) and constructs a narrative that quick, online justice of individual ends is desirable. At the expense of someone’s expedited emotional settlement, we create a self-perpetuating community police state.

The spread of misinformation or reliance on questionable truths that have not gone through channels of objectivity is an act against any just cause. It obfuscates the bigger issues that we must tussle with. When we pursue justice personally than systemically, we run the risk of taking down the pillars of justice, and in this case, a thorough and true investigation of misogyny in Singapore with it.

What happened?

The fires of online Singapore are ablaze this week. We are angry at what has transpired since Nicholas peeped at Monica in the showers of Eusoff Hall at NUS, when he violated her private space and modesty.

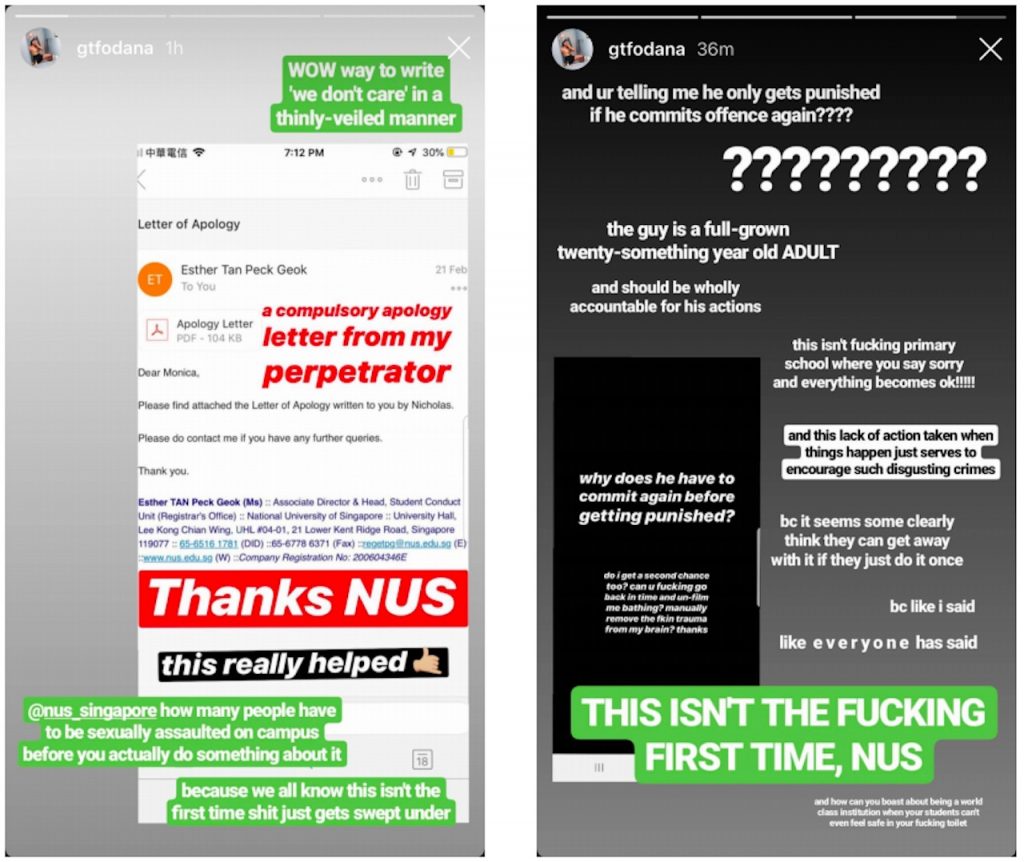

Nicholas filmed Monica while she was showering. After the incident, Monica approached campus security to lodge a report. Later, she would approach the police. The police would put Nicholas on a 12-month probation. NUS, meanwhile, had Nicholas write Monica an apology.

Since then, there have been countless opinions online, NUS issued a press statement, and a petition for the re-opening of the case is live.

The opinions that I will refer to are mostly from my Facebook or IG stories (both private and public accounts which I have access to in my personal capacity).

The main arguments that people have are against the likes of Nicholas and the institutions that determined his current legal and institutional positions (i.e. NUS, and the police):

Mainly, NUS was and is not doing enough to protect victims of sexual assault. They are attacking the perceived lack of prevention of incidents, and likewise a perceived lack of recourse for victims (either in the form of punishment of the alleged transgressor, or rehabilitation and comfort for the victim).

The police are perceived as lacking – the legal ends meted seem unsatisfactory; the transgressor having “only received a 12-month probation”.

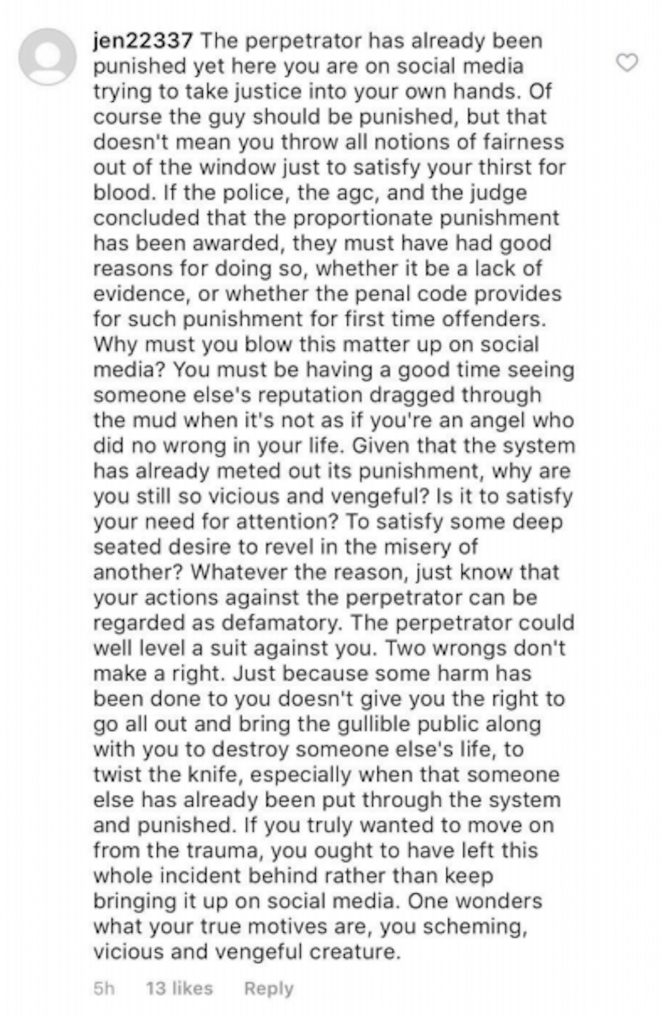

On the other hand, there is a smaller faction that believe this ‘social death’ Nicholas suffers online is just too much – the police and AGC know best. He has received his probation and “two wrongs don’t make a right”. To them, the speaking public is vengeful to no meaningful end.

Something must be said of these opinions. We must consider the impact of the speaking public who are calling for an active change (as opposed to the other faction calling for a cessation of Nicholas’ social death).

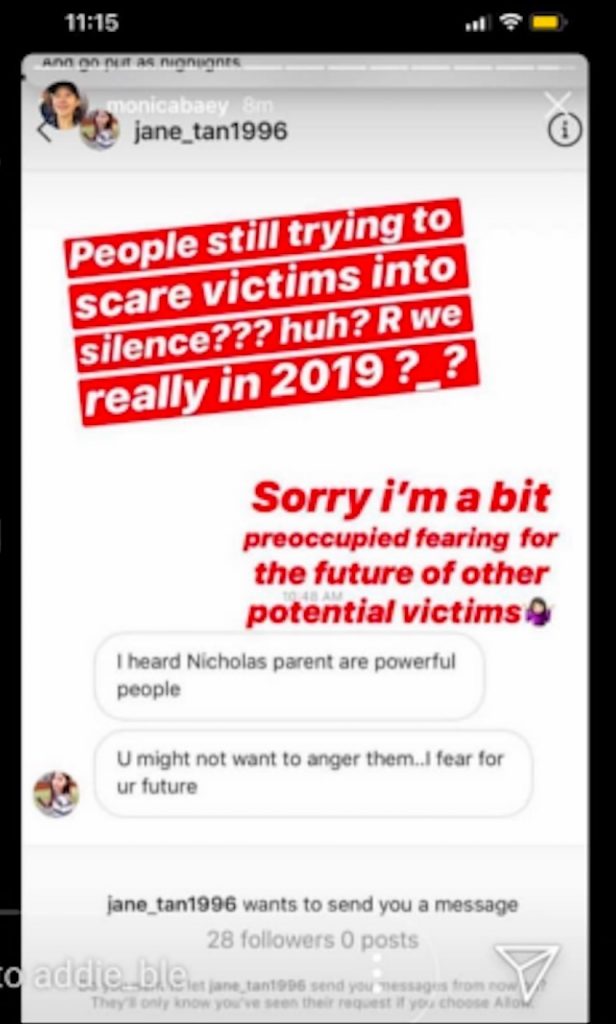

Their pitches and calls are premised on the assumption that the facts known to them, online, and not through an objective channel such as a court, are true. For example, it’s been said that Nicholas has “powerful parents”, and some are running the narrative that justice in favour of the powerful is not really justice. It was later revealed Nicholas’ father is a public transport driver.

It is not a matter of true or false. It is the matter that the information we receive or think to know have not been verified in anyway, and that we continue to demand recourse based on said information. In fact, we have dealt that recourse – Nicholas’ name, IC, and job has been robbed of their privacy. He’s been called a rapist, sex offender and even slammed by organisations as a “little shit”. Even his ex-girlfriend’s name has been outed.

The speaking public might answer to this that they owe nothing to the perpetrator. He should be prepared to face the music, however loud and discordant, from any direction. Further, he should not be offered second chances, lest we allow rape culture to thrive in Singapore.

Nicholas must be prepared to face the music. We must ask ourselves, the netizenry, are we ready to create a culture of justice from an inevitably inconsistent albeit collective vox populi?

Singapore has a peeping tom problem. We must stop rape culture and all its insidious effects.

Because we are inundated with news of women consistently being disempowered, we are allowing this narrative of harsher consequences for ill-acting men (though true and in need of our attention) to unnecessarily and unfairly obfuscate the narrative of due process and humanity. We act with our hearts against these transgressors, at the expense of systemic justice for all residents of our Singapore.

To be clear, this is not an ode against punishment for Nicholas. This is an ode against the hasty pursuit of one ideal at the expense of another. When we dox and ignore due process, we lose the means to achieve justice for anyone, including our women. We become unable to communicate, clearly and directedly, our collective vision for a more just future. We conflate two separate forms of justice and deal out two punishments: one by restorative justice system, and one by the retributive public. No meaningful progress can be made when we subvert our justice system for a quick victory through the social death of a perpetrator.

What is justice then? What should we do now?

In the end, this piece is not about which side is correct or not. This piece is the start of a discourse revealing Singaporeans’ (or at least Singaporean millennials’) dissatisfaction in the law, and a contempt for people who raise opposing opinions on controversial topics.

We need to realise that all parties concerned with this incident believe in justice. But, we all have different and inconsistent conceptions of justice.

While we all understand democracy as related to justice (petitions rallying many for single causes having authority to sway relevant authorities to action), due process and fair trial must be just as emphasised.

In Singapore, fair trial and due process is an important cornerstone of justice. The adversarial nature of trials in Singapore meant to draw out truths, with a judge to objectively assess them in fact and in law.

We must understand that truth cannot lead from untruths, and due process protects us from promulgating ideology and consequences from untruths.

But… there was no trial anyway leh?

Before any case reaches the ears of a judge, a number of things must occur. At the very start, a charge must be made out to the alleged transgressor.

Charges are made under the purview of the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC). Prosecutorial discretion is at the heart of this. Article 35(8) of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore states that the Attorney-General, as a Public Prosecutor, “shall have the power, exercisable at his discretion, to institute, conduct or discontinue any proceedings for any offence”.

Of course, if someone nicks a Snickers from 7-11, the AG will not hear any of this, and his other prosecutors will be on the case instead. In practice, this prosecutorial discretion is simply the discretion of prosecutors to pursue a charge or not. That’s why, sometimes, someone who has committed a clear crime of stealing, for example, can get away without so much as a warning. It’s difficult to compare the current facts to existing case law; there are many facts found and decisions made in the steps preceding the court trial and final judgment.

This changes the quest of justice from one of seeking punishment unto an individual into a quest for transparency.

In Singapore, the discretion is vested in the AG and is constitutionally protected. There is no prosecution guideline assisting prosecutors in making decisions consistently and fairly.

What do we do with our dissatisfaction at the 12-month probation? We cannot seek to take justice into our own hands as we have done and doxed, because our arguments are not based on objective and duly processed facts. We are faced with three options:

1. Ignore whatever happens and have (blind) faith in our legal system

2. Oppose the system and the concept of prosecutorial discretion in its entirety

3. Allow the system to persist, but call for transparency in the procedure of discretion

Barring the first option, we must be consistent and firm in our understanding of the pattern of law and governance that our country rests on, and the pattern we want to see. This will take us into a whole foray into constitutionalism, Confucianism and paternalistic governance that is far beyond the scope of this article.

The same goes for our dissatisfaction at the actions of NUS. We should demand for transparency in the coming of their decisions, the reasons and the facts that they have concerned themselves with.

Respecting women, decrying voyeurism

Our dissatisfaction for the treatment of women in Singapore, however, cannot be so simply addressed as above. But with a collective understanding of justice, we can begin to pave a way toward just treatment of any who is disempowered in our country.

We can meaningfully ask ourselves: how can we prevent this flippant attitude towards women? What is the general attitude, especially of our youth, about privacy and consent? We need to understand not just the facts of this case, but so many others, and the reason for any unsavoury attitudes people have surrounding sex and consent. Before that, we must understand precisely what even is that attitude. We need to understand the power dynamics between the two majority genders in Singapore.

A larger conversation about sex, consent, misogyny and justice must take place.

This incident also reminds us of the very temperamental and very powerful influence of social media; we cannot be haste in our call for change without understanding our issues with granularity.

With an understanding of our issues, we can go on to ask more questions: What do we truly want from our institutions? Do we seek blanket retributive force? What preventive measures do we want or need in place?

When we dox, we substitute our own sense of justice for due process. When we dox, we lose the ability to answer these questions as a community, and we silence voices that seek to ask these questions.