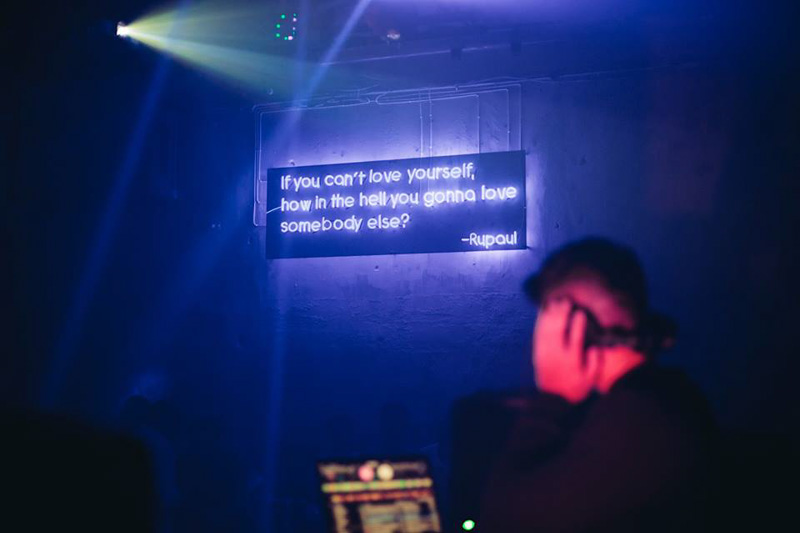

I am standing in the dark, struggling to read the neon writings plastered on the wall. As Rezal, Fiq, Malik (my friends from NS), and I dance ecstatically beneath the luminescent blue sign that hangs over the dance floor, Britney Spears’ ‘Toxic’ blares through Peaches, the club we’re in. Excited, Fiq and I climb atop the platform.

Now, the neon sign is behind us, but we don’t have to turn to know what the words are. RuPaul recites them at each elimination in her ever popular reality TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race, and Fiq is now screaming these words on the way up from a booty drop: “If you don’t love yourself, how in the hell you gonna love somebody else?”

“Drag really is an art form of its own. […] Through our makeup, outfits and performance routines, drag queens create art that represent our everyday struggles and emotions,” she says.

For Veron, it is only when she is in drag can she express her true self. Yet in National Service, Veron is Fiq, and has to shed his drag persona due to the alienation effeminate men sometimes face.

She adds, “Wearing women’s clothing is considered taboo, or haram as we call it (in the Malay-Muslim community).”

While Veron isn’t ignorant of the fact that there are still those who see her as a sinning crossdresser, being in drag remains cathartic as she often performs for a supportive audience that cheers her on. For her, ”I do drag to feel confident (and) personally believe that we should all help each other feel more accepted in society.”

Growing up, Veron was frequently on the receiving end of ‘bapok’, ‘pondan’ and ‘kedi’, all derogatory Malay terms that refer to men who dress up as or behave like women. Having been considered too effeminate in primary school, I share this experience with Veron.

For example, I never enjoyed playing soccer and often preferred using my recess time to chat with female schoolmates about the latest Disney TV shows. This was enough for me to be ostracised, having failed to subscribe to what most primary schoolers would consider “manly”.

These days, however, Veron and I are able to hurl these very insults at each other, comical proof that a system that once rejected us for being ourselves can no longer subjugate us.

While Drag Race has contributed substantially to the growth of Singapore’s drag scene, Arya believes that this development poses a challenge for budding drag queens who “(do not understand) the work that goes into the craft”.

“At the end of the day,” she says, “(Drag Race) is a reality TV show filmed in Hollywood. It is extra flashy extra exciting extra everything and people sort of expect to see that for every single drag show they go to. That’s kind of a problem.”

To tackle these challenges, Veron often pushes the boundaries of her drag persona. Today, she has dolled herself up in a baju kurung for the photoshoot, as she wants to “showcase the beauty of the Baju Kurung in an unconventional way.”

For those who don’t know, the baju kurung symbolises Malay femininity, and Malay women often wear it during weddings and Hari Raya.

With this photoshoot, we wanted to question: Can a drag queen represent Malay conceptions of femininity?

These are questions that the Malay-Muslim community must consider, as alternative yet viable conceptions of identity have been inevitably introduced through globalisation and our access to international media.

As I stand in front of the Masjid Sultan photographing Veron, a makcik doesn’t stop staring at us. I’m reminded that this is the same community that has not accepted her identity as a drag queen, and find myself humbled by her participation in the shoot. It may not be obvious to passersby, but by being in an area closely associated with the Malay-Muslim community, Veron is taking a courageous step out of her comfort zone.

”As a drag queen, you literally grab everyone’s attention when you’re out on the street in drag,” Veron says, “From both Singaporeans and non-Singaporeans alike, some people give me a “look”, and some will compliment me.”

We cannot be sure what the makcik thought of what we were doing, but according to what Veron has experienced, “some even dare to cuss [at me]”.

She adds, “The normalisation of gender bending through artistic expression has been something that has been happening ever since Drag Race started becoming increasingly popular over the past few years.”

Undoubtedly, Veron is part of this global trend as well; her favourite Drag Race queens are Violet Chachki, Alyssa Edwards, and Naomi Smalls.

At the same time, she remains acutely aware that she is ultimately still subjected to her parents’ opinions and approval, knowing full well that they “will very likely disapprove of drag”.

While her siblings are indifferent towards her doing drag, Veron suffers from constant anxiety about her parents finding out that she does it.

Veron confesses, ”I don’t think I’ve thought about (telling my parents) yet. […] [If they found out], that would really make me re-evaluate my love and passion as an entertainer.”

While being a full-time drag queen is her ultimate dream, Veron contends with a more challenging and unforgiving reality in her conservative Malay-Muslim social context, pointing out that ”I have to be really discreet about (being a drag queen) whenever I can,” even though “performing, entertaining and making audiences happy is what I ultimately want to do.”

Since she cannot openly work towards this dream at home, she performs for us back in our NS bunk.

Later, after an Instagram Story Poll, Malik tells us that Rezal won. Although Veron loses this one time on social media, she has bigger battles to fight. As a Singaporean drag queen, “I want to quash the mindset that drag queens are merely crossdressers so that the world will see drag queens as equal to other artistes.”