This story begins, literally, with a punch.

Scene: Classroom, Primary Two.

Players: Heckler and me, a new transfer student.

Me: “Stop bugging me.”

Heckler: “But you’re so short. Hit me lah.”

So I did. Curtain down.

That was the one and only time I ever punched anyone. And yes, I am short—140 cm tall to be precise, at last measurement.

Soon after that punch, I was diagnosed with Turner Syndrome. This came after countless blood tests and discussions at NUH, and as a 7-year-old kid, I knew little about it, as did the doctors because it was not very well-known in the 1980s. Even today, Turner Syndrome doesn’t often make the news.

What I do know is the aftermath of my diagnosis.

I started growth hormone therapy, which involved injections every single night, from the age of about 8 to 18. It was mostly my dad who gave me the injections, although I had to do it myself when neither he nor my mum were available. (Trust me, unless you’re into self-tattooing or something, it’s not easy to stick a needle in your own thigh)

On the bright side, after about 3,650 nightly injections, I am no longer afraid of needles. And I gained about 5 cm in height from them, which is about average.

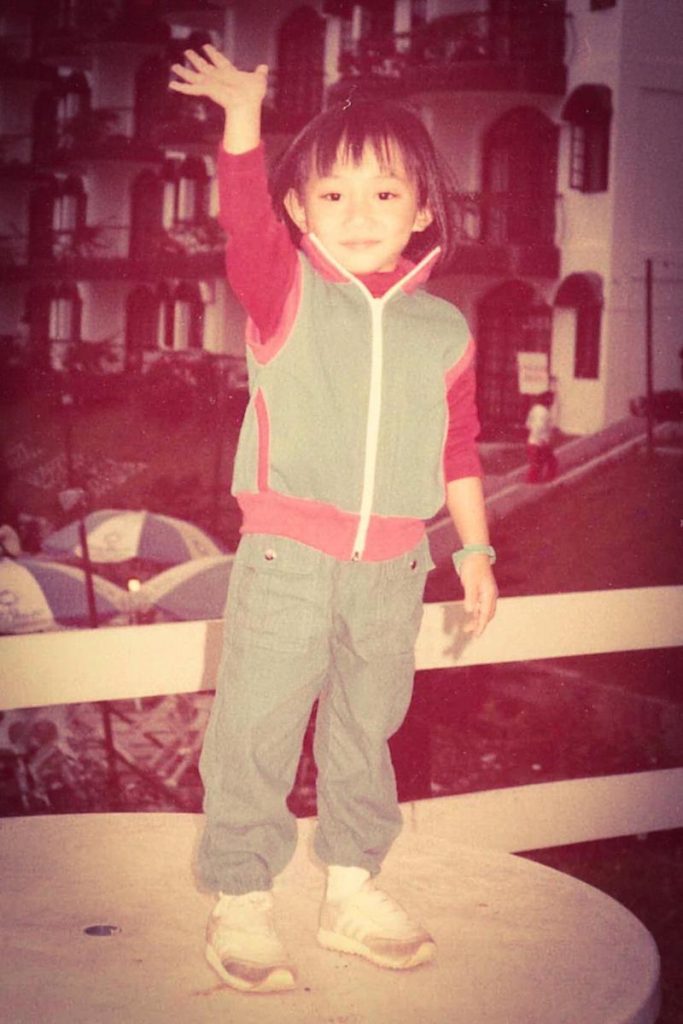

Injections aside, I had a pretty normal childhood. I sang in my primary school choir, did gymnastics in lower secondary school, played softball and chess in junior college, and wrote for all three school magazines. Not very exciting or dramatic, I suppose. But we can’t all have lives like a John Green novel.

It helped that my parents and teachers generally didn’t give me any “special treatment”. Not that I expected any; in fact, I would probably have protested.

Which leads to a strange dilemma: to accept help, or to suck it up and do what “normal” people would?

I was super embarrassed—paiseh lah, I thought. And I said no, it’s fine, I don’t need it, thanks. My classmates would laugh at me! But in the typical fashion of adults, I was given the board anyway. And in the typical fashion of a teenager who discovers that sometimes, adults do know better, I found that it really was more comfortable.

The ribbing, thankfully, was minimal.

And then, 25 years later, I was transported back to that day. Last November, I attended Kit Chan’s concert at the Esplanade. Soon after my friend and I took our seats, one of the ushers offered me a booster seat! I was torn between embarrassment and gratitude.

In the end, pragmatism won out (hey, I’m a Singaporean born and bred) and I accepted the kind offer.

Speaking of pragmatism, these days, I find myself heading straight to the kids section at Uniqlo and ordering kids sizes when I shop for clothes online. I’ve saved a bunch of money, I can tell you.

But I wasn’t always so ready to do that. Especially in secondary school, I used to be a lot more self-conscious. Having gone to an all-girls’ school, I remember thinking: I’m the only one who’s not getting breasts.

Sure, my parents and doctor had told me right from the start what TS was, so I was expecting that I wouldn’t be developing like the other girls. But still, it’s a little difficult not to think about breasts when you’re surrounded by them.

To help explain why I wasn’t developing like the other girls, the UK’s National Health Service defines TS as follows:

Turner syndrome is a female-only genetic disorder that affects about 1 in every 2,000 baby girls. A girl with Turner syndrome only has one normal X sex chromosome, rather than the usual two. This chromosome variation happens randomly when the baby is conceived in the womb.

The symptoms:

Almost all girls with Turner syndrome will grow up to be shorter than average, with underdeveloped ovaries.

Around 90% of girls with Turner syndrome don’t produce enough of these sex hormones [oestrogen and progesterone], which means—

1. They may not begin sexual development or fully develop breasts without female hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

2. They may begin sexual development but not complete it

3. They may not start their monthly periods naturally

4. It’s likely they’ll be unable to have a baby without assistance (infertile).

To put it simply, females with TS are not only short, but we mostly cannot have kids. (Okay disclaimer: it’s not impossible, just very difficult.)

I MAY BE KID-SIZED, BUT I AM NOT A KID.

No periods, no mess. No kids, no headaches. Callous? Maybe. Apologetic? No.

Some women might say they’d feel incomplete not being able to have kids. Again, not me.

To me, I am every bit as complete as any woman. My take is, women are much more than just child-producing factories. That is not our sole function, thank you.

Which is why I was quite resistant to taking oestrogen pills to help with my hormones. Starting from about age 15, the pattern was: three weeks of pills, one week of periods. And I hated that one week each month. In the few days leading up to it, I never liked the way I felt: worried, emotional, anxious, moody, depressed. I never felt like myself during those ten days or so. Hormones drive you nuts.

At the same time, I don’t mind admitting that even as I’m pushing 40, I have never dated.

I can’t say that I’m not open to it, just that so far it hasn’t happened yet. And while it is tempting to put it solely down to my height (or lack of it), I have to admit that on my part, I haven’t been really attracted to anyone. Not enough to act on my feelings, anyway.

And so, as I have always told my parents, if it happens, it happens. If not, this is 2019, isn’t it? I earn my own keep; I am capable of looking after myself.

Which I confirmed on my first solo holiday overseas to Sheffield and London. And after that, to Tokyo and Kyoto.

But that was only as an adult.

Until the year I turned 17, when I entered junior college, my parents weren’t comfortable letting me use public transport. Before that, my grandfather would drive me to school and pick me up after. Which was annoying to me because I felt stifled. More than once I told my parents, hey, I can take the bus! I’m not dumb.

In response, they always said it’s not about my brains, it’s about my safety.

Pfft. I know you’re worried about me. I may be kid-sized, but I am NOT a kid.

There was even one family holiday in New York when we went to visit the Empire State Building. Our tour guide had the cheek to suggest getting me in at the kid’s price, even though I was 16 at the time.

I could only hiss under my breath to my parents: “It’s not right! I’m way over the age limit!”

But they said: “He’s just helping us.” Call me stubborn or silly for wanting to pay more, but excuse me for believing in doing the right thing, and just wanting to be treated like everyone else.

Even then, not everything is so easily shrugged off.

I am not a fan of items in high places. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve had to find a step stool or a ladder in Kinokuniya to get a book that just happens to be on the very top shelf. (I do ask the friendly staff to help sometimes, but only if I can’t find the necessary equipment.)

And on public transport, I have missed my stop simply because everyone else is taller than me and I sometimes just cannot see where I am. Sometimes I find myself standing next to someone with body odour, who has their arm raised while holding on to a strap overhead.

As you can imagine, I am at just the “right” height to get the full effect of eau de armpit.

At times like this, I do mutter a few choice words under my breath and wish I were taller.

This is why I like doing things where height doesn’t matter. Besides being a hopeless bookworm, movie buff and arts lover, I sing in my church choir. And I have a steady job as a translator.

The only exception is my interest in photography. Sometimes I feel hampered at least a little, especially when I know I would get a better shot if I were just that much taller. But then I’m pragmatic, remember? So I just get the best shot that I can.

Come to think of it, it’s easier for me to shoot kids and animals at eye level. And at least one friend has mentioned that they can tell which shots are mine even without asking, because of the angle and perspective. So I guess that’s not a bad thing. And if the shot I have in mind just doesn’t happen, I’m prepared to let it go.

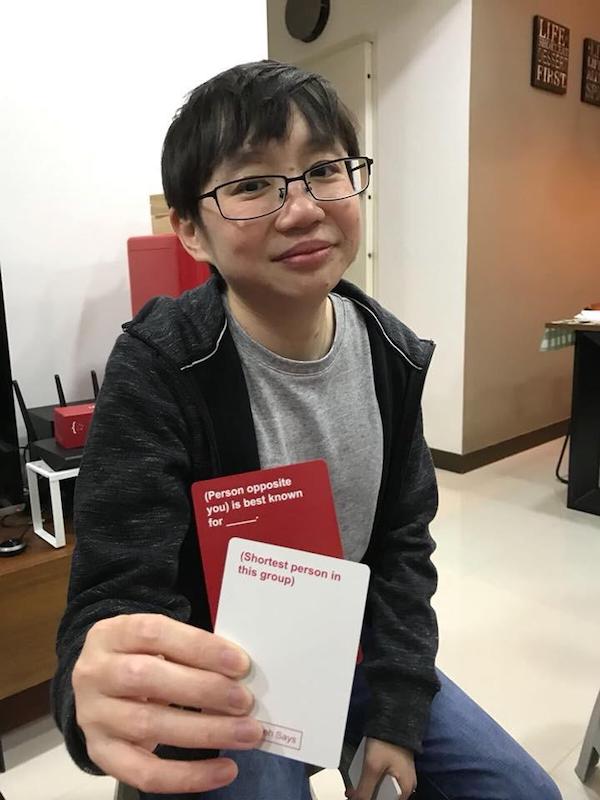

I have also learned not to take comments from other people too seriously. Short jokes are perfectly within limits; in fact, I have developed a matter-of-fact sense of humour about it—I have a tote bag that says “I’m not short, I’m a hobbit”, and I’ve shared memes on social media about short girl woes.

My friends sometimes tag me on memes too, and frankly I am grateful to be able to share a laugh about it now. It helps to have friends who send you stuff like this:

I’m trying to say that it’s OK to be different. It’s OK to be you, to do what you enjoy, no matter what everyone else says or thinks. Don’t be defined by just one thing in your life. You are more than your job, your exam grades, your family background, your medical condition.

You are the sum of your things you’ve done, the people you’ve met, the places you’ve been. The books, movies, music that you like. They are you.

Make you count.

Have a story of your own to share? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.