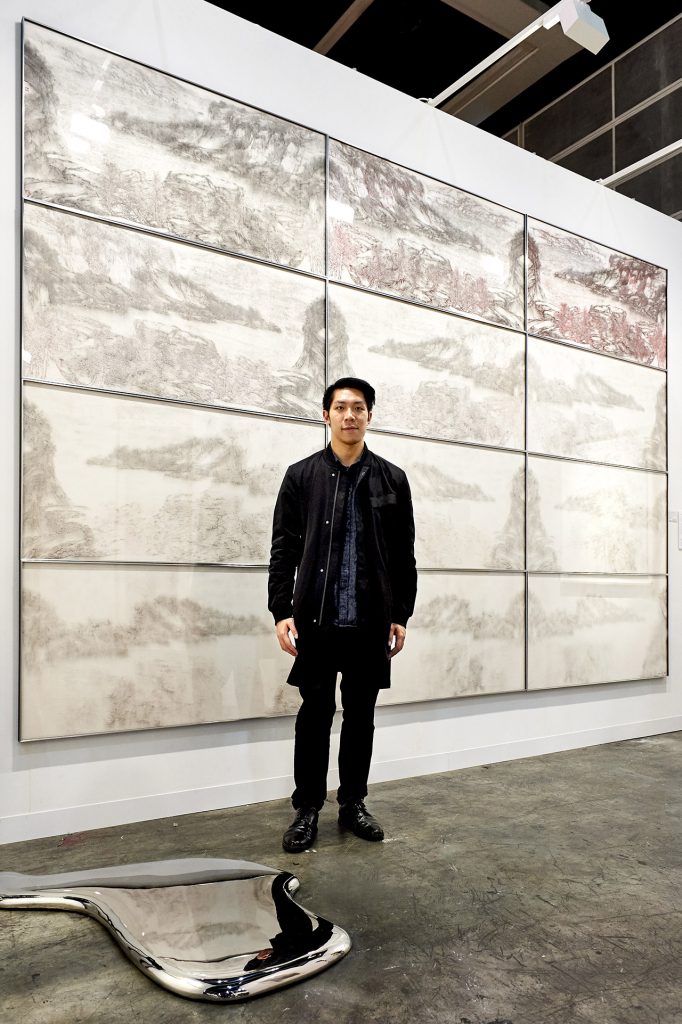

Using ink-and-brush, as per the ancient Chinese tradition which requires years of rigorous training, felt daunting. Not only as it was a medium that did not find itself in his western-aesthetics -orientated curriculum, but also because his father, the venerable landscape painter Hung Hoi, was a master in the art.

“Growing up traditional Chinese art felt intimidating to me,” he says. “I struggled to find my voice through that medium.” It was only when he was at Chinese University, from which he graduated in 2013, that he started to inject traditional ink techniques into his more conceptual and mixed media works.

In a series of works meditating on Hung’s relationship with the art form, he invited his father to paint a landscape piece over which he makes his own alterations, pouring water over the imagery such that his father’s terrain begins to fade.

It’s a piece that explores influence, authority figures and the shifting aesthetic landscape as art forms pass down generations, and speaks to the role many Chinese ink artists play today as bridging the old world with the modern.

Chinese culture has a millennia old history with the delicate and expressive art of ink, which in bygone times would involve years of dedicated, repetitive training at the hands of a fastidious master.

Learning by imitation is part of the process of mastery, as is developing a deep understanding of the mores and principles that underpin its aesthetics.

During the cultural revolution and aftermath, classical ink art was driven underground.

Some artists switched to propagandizing mediums of socialist realism and Hong Kong came to serve as a safe haven for a pioneering generation of ink artists influenced by developments in the western art world while retaining values of their heritage.

“Since the early 20th century, Chinese painters started to find different means to modernize the Chinese painting. Most of them learned and combined ideas and techniques from Western modern art,” says Wilson Shieh, an artist born in Hong Kong in 1970, just as the SAR’s modern ink art movement was beginning to establish itself.

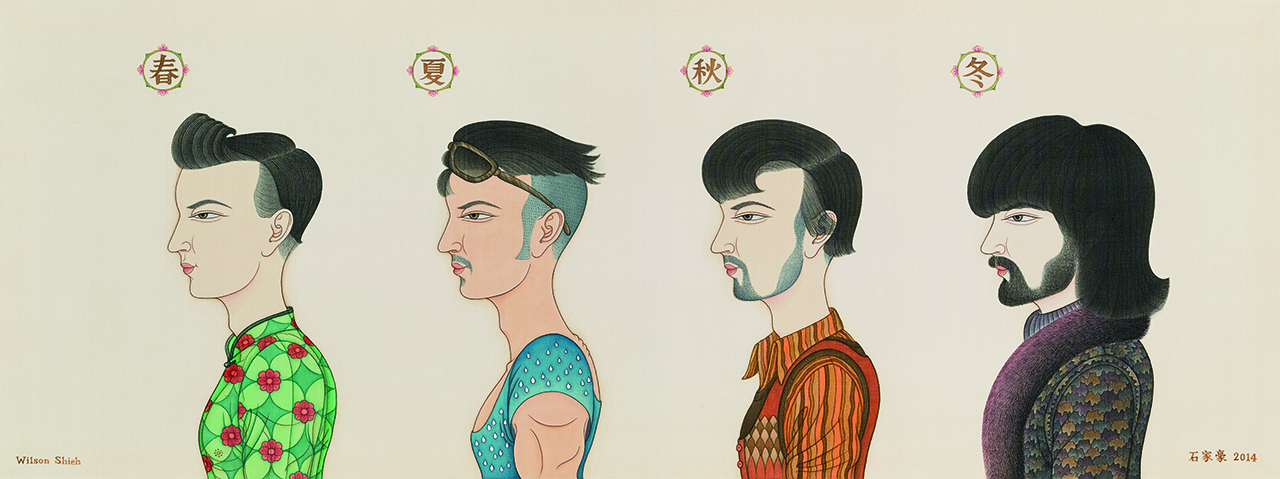

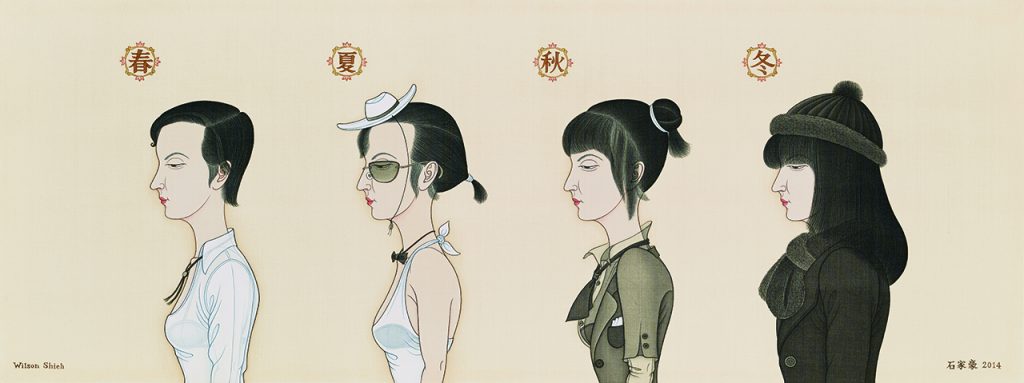

An ink artist for twenty years, he uses a traditional brush technique called Gongbi, which has 2000-year-old roots in the Han dynasty and is used to depict realist images with meticulous and detailed strokes.

Influenced by surrealist narratives and Japanese Ukiyo-e print and Chinese forms, Shieh depicts his singular vision of contemporary Hong Kong.

Like other local contemporary ink artists, connecting old ways of seeing and depicting the world with modern themes serves to innovate an art form that both pays homage to Chinese culture and speak to metropolitan Hong Kong society.

This has given a boost to the visibility of Chinese contemporary art, which has, across mainland China, been returning to its hitherto politically-unseemly ink art traditions.

Hong Kong, where the contemporary art form has been able to develop without restraint, is an important foothold for the medium. But despite this rich legacy, concerns prevail that Hongkongers today don’t have enough access to or awareness of classical ink traditions.

“We have… almost no education of Chinese ink art for our elementary school. Only some art teachers teach Chinese painting on a voluntary basis,” Shieh says.

That writing Chinese characters and developing brushwork skills are becoming increasing separate activities might serve to further drive a wedge between the Chinese and their ink legacy.

Shieh notes that he sees an increasing number of young ink artists. Hung Fai agrees.

“Ink art is something that is nourishing. It is a different visual language from digital and film arts…but they are all important art forms today,” says Hung. Ink art offers something that the digital arts as yet can’t: a sense of connection and continuity with generations stretching back centuries.

“Because I invite my father to work with me, there’s a lot of intimacy in my paintings,” Hung says.