My brain seizes up as I tried to think of a way to tell him gently—but firmly—that he had been spending the past one-and-a-half hours with another publication. An awkward silence ensues. Zachary, our photographer, sensing trouble, breezily offers: “The RICE office is at Ann Siang.”

These sorts of faux pas (in his emails to me, Sonny has called me “Boo Ping” and “Ping Yeo” even though the company-mandated signature states my name as “Boon Ping”) can sometimes come across as rude, or even a power play to show how little you care about the person with whom you are corresponding.

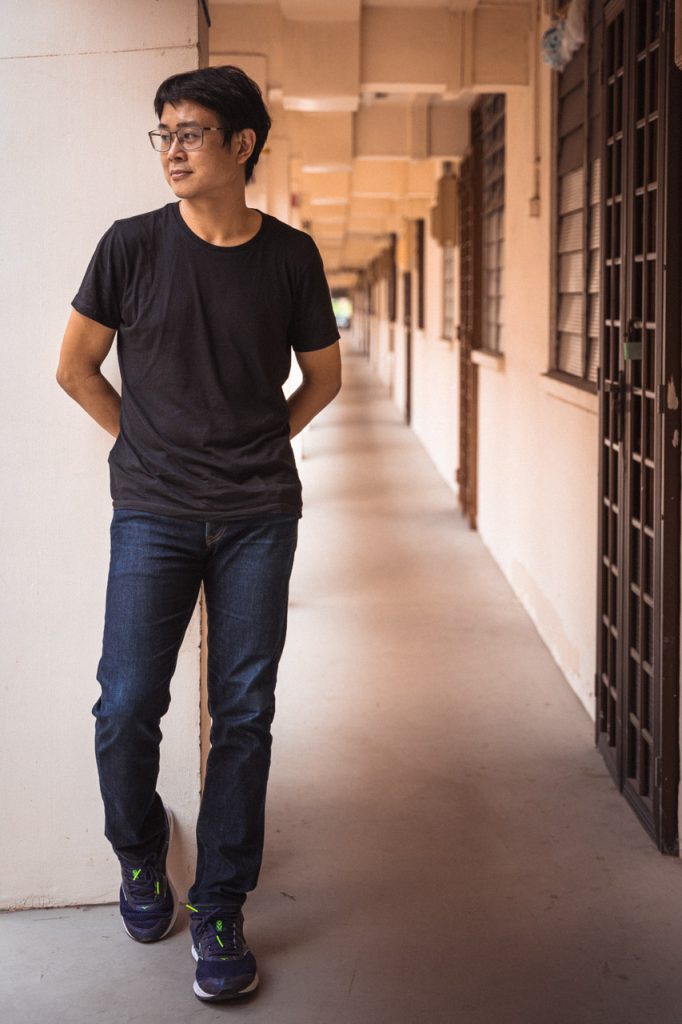

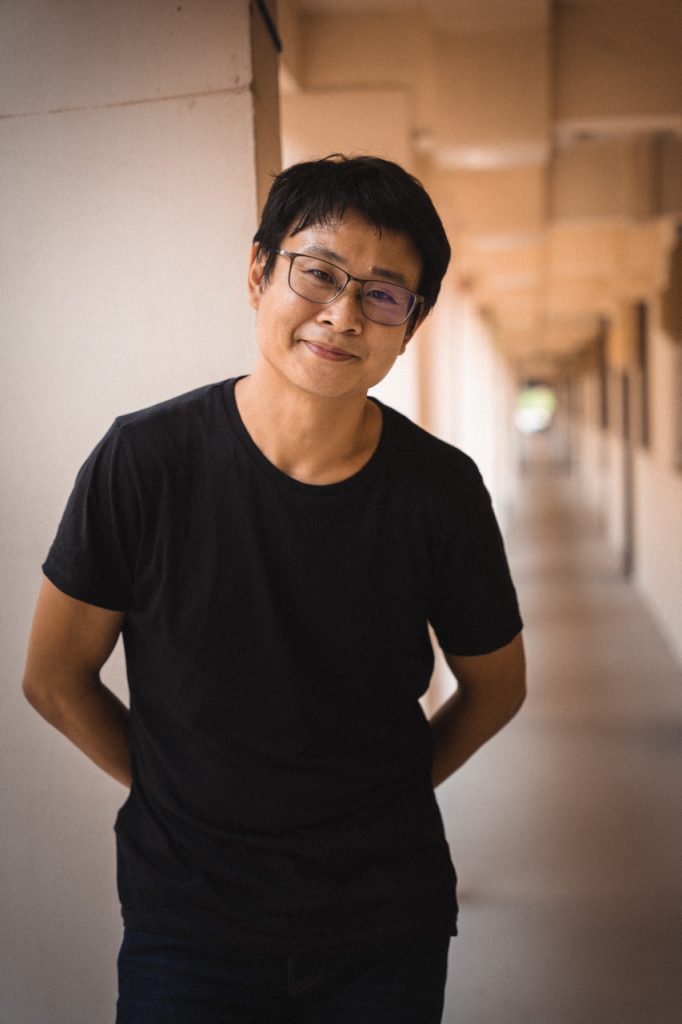

But Sonny’s slip-ups are not malicious. Instead, they seem to be a result of how he lives: always swimming in his head, occasionally breaching the surface to tend to drab matters of reality, before diving into the technicolour world of his art again.

Sonny, in other words, is an artist through and through.

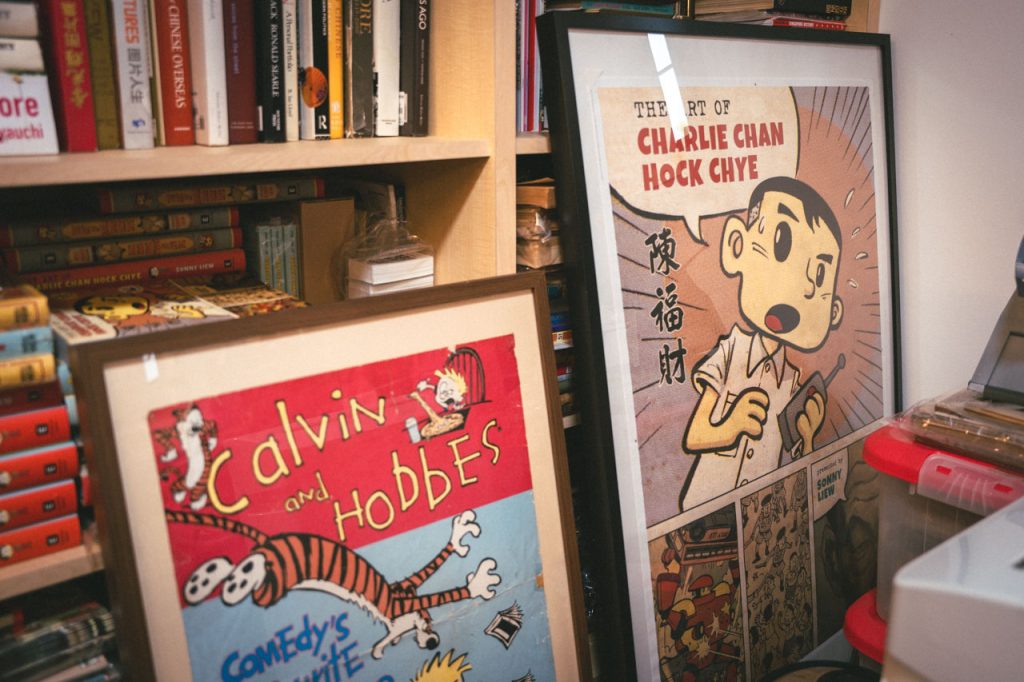

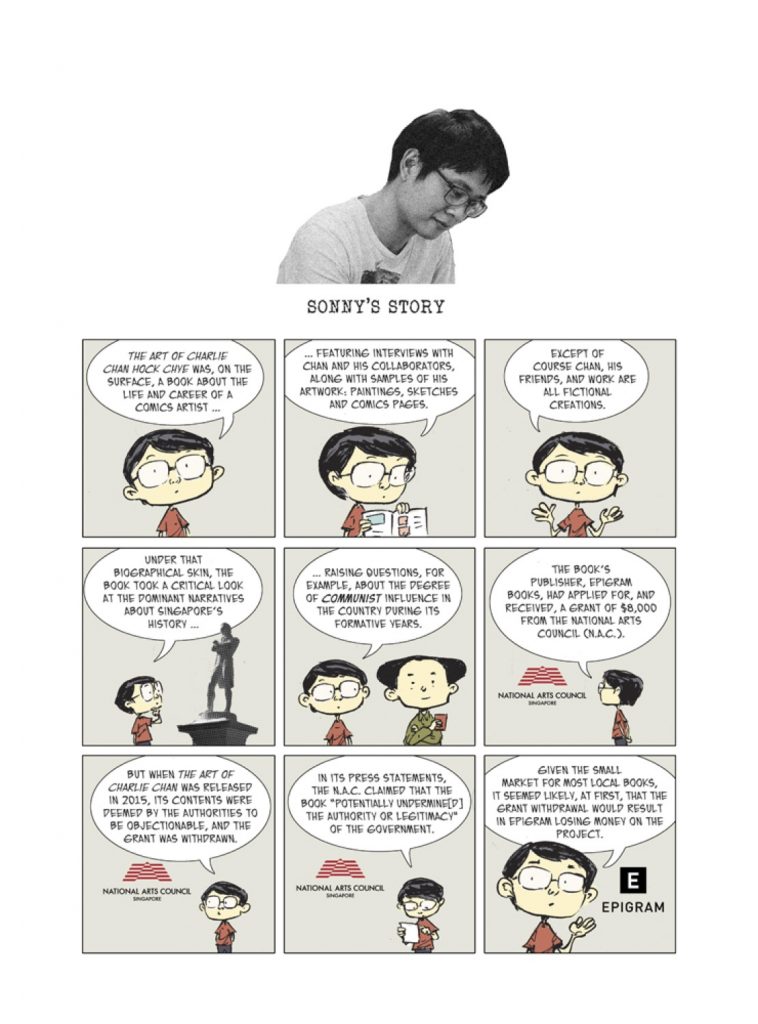

This is not to say that Sonny is an acolyte of the aesthetic movement, believing in art for art’s sake. After all, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (henceforth Charlie Chan), the book that catapulted Sonny to global fame, is at its heart an interrogation of Singapore’s founding myths: it excavates the history expunged from our textbooks and official narratives, while retelling this narrative in a dazzlingly inventive and captivating way.

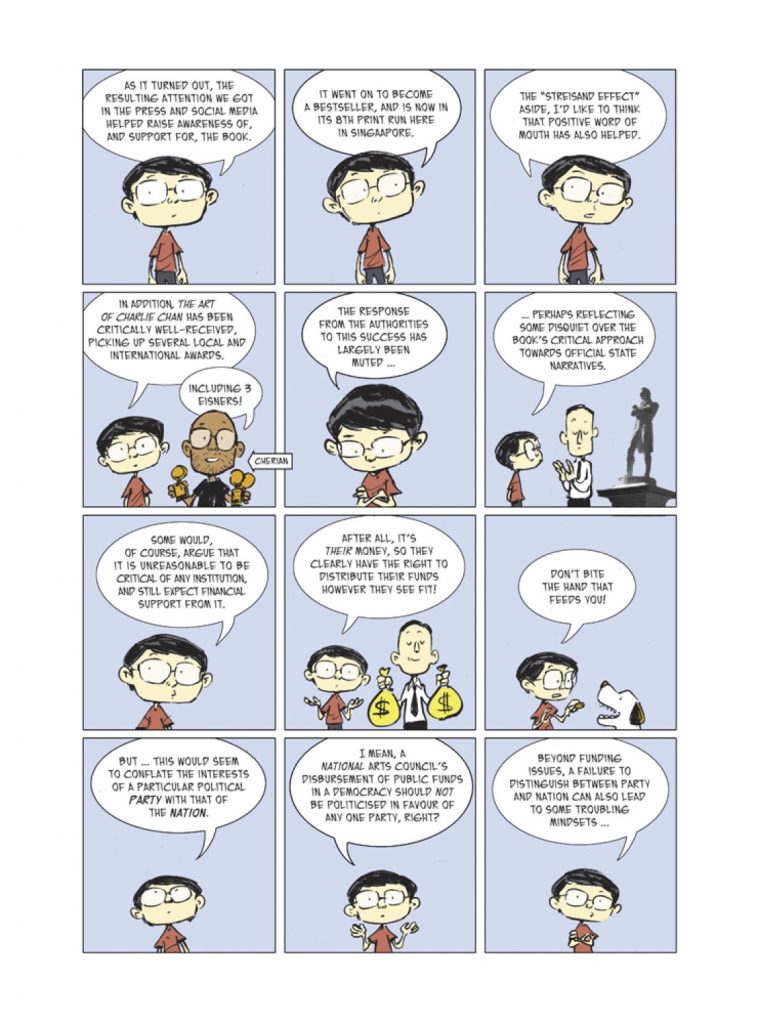

Little wonder, then, why Charlie Chan won Sonny three Eisner Awards, bagged the Singapore Literature Prize in 2016 (the first time it went to a comic book), appeared on multiple “Best Of” lists internationally … and, as much as I’d like to list all the accolades Sonny has received for the book, they really are far too extensive to state in full.

Charlie Chan is also one of the few books that has enjoyed popular reception alongside its critical acclaim. Just last month in September, Epigram Books, which publishes Charlie Chan in Singapore, launched a new 5th-anniversary edition of the book—no mean feat in Singapore’s small market, where selling 1000 copies of any book is cause for champagne popping.

“The good part is that Charlie Chan has legs, it’s still part of the conversation,” Sonny reflects when I ask him how he feels seeing his book possess such longevity.

“The scary part is that it’s been five years. In my mind, it was not too long but clearly time has passed … and I haven’t done my next graphic novel yet.”

For Sonny’s fans, by which I mean any human being who is literate, there are no questions more pressing than: What is Sonny’s next book about? And when is it coming out?

Sonny is tight-lipped about its contents, only letting slip that “it’s about capitalism”.

Okay, fine. I dislike spoilers anyway. I’ll be satisfied as long as I have a date to look forward to—

“I’ve not really started real work,” Sonny admits with a flash of guilt as my stomach sinks, “I’ve done some research, I’ve been thinking a lot about the structure, the characters, narrative … but it’s something you really have to sit down and grapple with before it can take form.”

Sonny has been taking such a long hiatus from his new book because it was almost necessary to do so after writing Charlie Chan.

“I felt that I had poured everything I knew into [Charlie Chan] … I needed to reboot my brain, recharge, learn new things before I could do my new book. It can’t be just another fake biography that touches on a different topic.

“I’ll do it this year, probably, and it’ll take me another 2 to 3 years to complete.”

As that number sinks in, he pauses as if only just confronting it, before continuing.

“That gap between Charlie Chan and the new graphic novel seems like it’s going to be 7 years. When I first heard about Kazuo Ishiguro and how it took him 8 years to write The Buried Giant, I thought, ‘It’s so long!’ but now I realise my situation is not too different from his,” laughs Sonny self-deprecatingly.

What has Sonny been up to since Charlie Chan, then?

“After Charlie Chan, I worked on Doctor Fate, Eternity Girl, The Antibiotic Tales, some illustration projects in between … right now I’m working with Cherian George on Red Lines: Political Cartoons and the Struggle against Censorship, a book that’s coming out next year. He’s writing that, I’m just illustrating.”

The balance between commercial and creative work is a struggle for artists everywhere.

Commercial projects pay well: if you draw for the Big Two, that is, Marvel and DC, a monthly salary in the ballpark of $10,000 is not out of the question. But, to Sonny, some of these projects are “not as engaging because it feels like I’m only using half my brain—it’s not my thoughts that I’m expressing, it’s the writer’s thoughts.”

I commiserate with him and whine about writing sponsored articles.

“It’s the most fun, right? Best thing ever,” Sonny intones dryly as a playful smile creeps across his face.

Still, commercial work is a necessity for cartoonists, especially in Singapore, partly because the local market is too small to support artists who want to devote their time to creative work fully.

“The comic scene here is not as developed. We don’t have the critical mass, the numbers for it, both in terms of readers and artists. With a population of 5 million, compared to the US or China, our numbers are not going to match up.”

But Sonny quickly qualifies this statement, recognising that Singapore boasts many significant industries, such as financial services and electronics manufacturing, despite our small population.

“It’s also to do with the industry itself, the way it’s structured, private and government support … I would say the K-wave is one example where it’s clear that state support has had a big impact on the art scene in Korea. They spent a lot of money pushing the brand.”

(Ever the conscientious researcher, Sonny sent me two links to back up his claim one day after our interview.)

His mention of government support seems as good a time as any to ask him about his complicated relationship with the National Arts Council (NAC).

I start with the most straightforward: despite knowing the important role state support plays in cultivating the arts, why did Sonny decide to return the grant NAC awarded him for his next book?

“It’s mainly to do with creative freedom and control,” Sonny explains. “Once the grant was given, it’s clear that they wanted updates every now and then, and that put pressure on you for delivery dates.”

More troublingly for Sonny is how NAC “will review the content” of the book.

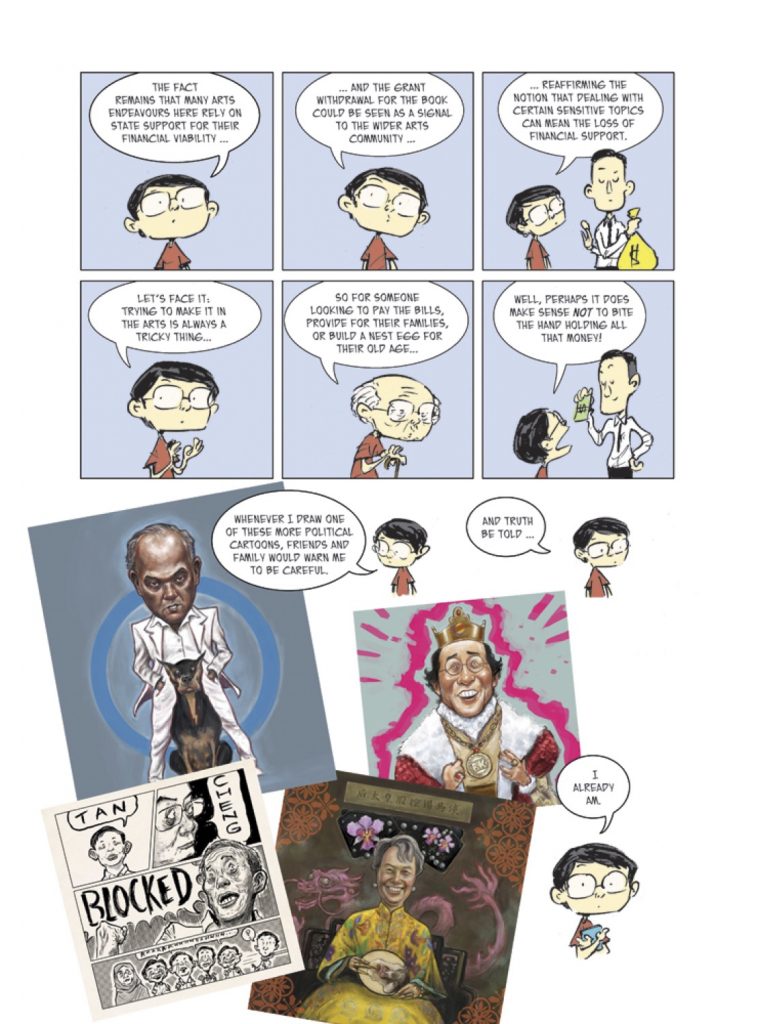

Sonny and his publisher have already been burned once by NAC’s process. The first edition of Charlie Chan is somewhat of a collector’s item today because they are the only ones to feature the NAC logo printed on their cover—a logo that had to be hastily covered with a sticker when NAC “reviewed” the book and withdrew its $8000 grant after the book had been published.

The statutory board’s reason?

“The retelling of Singapore’s history in the graphic novel potentially undermines the authority of legitimacy of the Government and its public institutions and thus breaches our funding guidelines,” pronounced Khor Kok Wah, then-senior director of NAC’s literary arts sector.

Not wanting to portray himself as a martyr for the arts, Sonny deflects the scrutiny on him and adds, “It wasn’t just my book. I think it was also Jeremy Tiang’s book. It had the same issues, it got its grant pulled for content.

“At that time, I felt it’s better not to have to worry about that aspect.”

Three years after Sonny decided to return NAC’s grant for his second book, he declares he has no regrets.

“But I do still wish that there were more open conversations with NAC,” he stresses. “I think that NAC as a whole should be run independent of ruling party interests. It’s still seen as a stat board, and the idea that the government and the PAP are really inextricably intertwined is an issue.

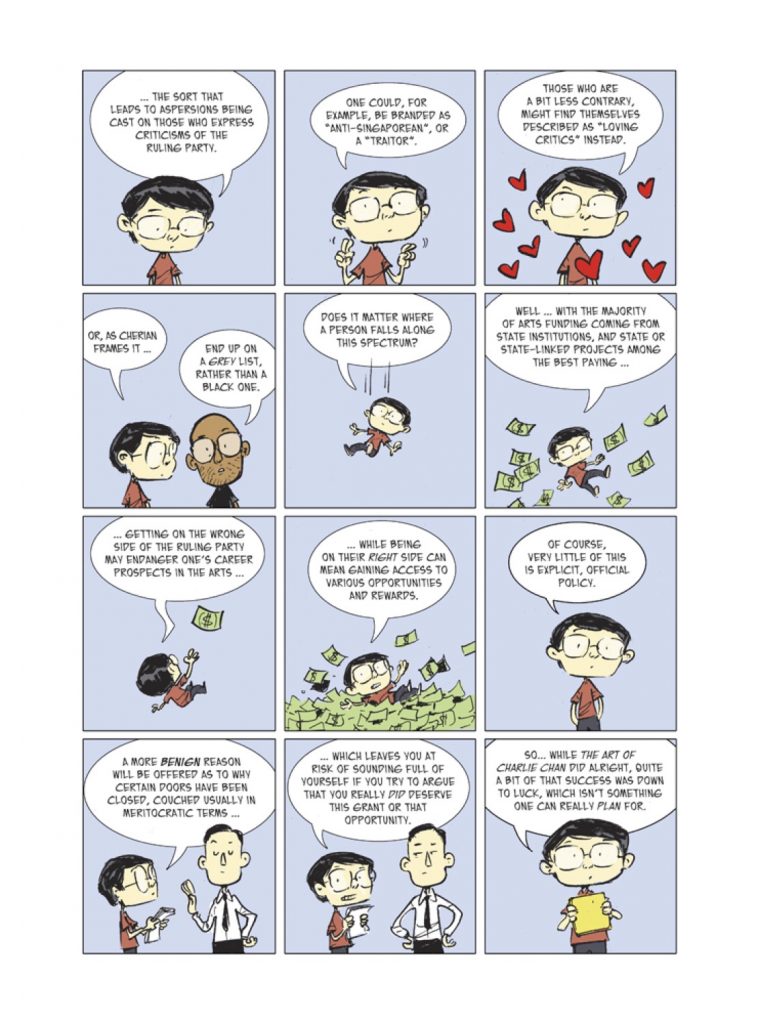

Sonny is alluding to the fact that NAC tends to reject funding applications from projects that are critical of the government—in essence, the PAP, for all of Singapore’s modern history.

The defence that the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (under which purview the NAC operates) trots out is that “it also needs to take into account the views and concerns of the public at large, due to its role as a public institution”, especially because public institutions are funded by public monies. Therefore, “the government also sees the arts as a way to engage the community and build a stronger sense of national identity.”

Sonny is not convinced: “There’s an easy argument against that. 40% of Singaporeans didn’t vote for the PAP, so why don’t you just give 40% of the money to ‘anti-government’ projects?”

It’s clear from his responses that Sonny believes that art should not be subjected to the panoptic gaze of the state.

Roleplaying as an NAC director wrapped in a locally designed cheongsam, and who believes that the function of art is to further happiness, prosperity, and progress for our nation, I boom at Sonny: Why is freedom of expression so important to stubborn artist-types like yourself?

“Cherian, in his book Red Lines, will argue that [the ability to draw satirical cartoons without invoking censure or the censors] is a good signifier of how free a country is … In an ideal liberal society you should be able to disagree with a cartoon but acknowledge that it’s well done, clever, or funny, without taking offence or getting it banned,” Sonny answers.

“The government has always taken the line that you shouldn’t mock or caricature local politicians. So you can do Mahathir, you can do Reagan, Thatcher, whatever, but don’t mock our leaders. They have this idea that [such portrayals] will erode their authority and affect their leadership.

“It’s like in China now. Xi Jinping doesn’t like the Pooh bear.”

Even though Sonny lauds social media for allowing the proliferation of political cartoons in Singapore—there’s “less gatekeeping than in ST or anywhere else”—he is cautious about celebrating it as a paradigm shift.

“There was a guy who did a strip called Demon-cratic. He got called up to the police station. And since then he stopped doing it.”

With the advent of social media, the barriers to publication have changed. But—like in China—the regime has not.

“That’s why traditionally, we have a lack of political cartooning here,” Sonny surmises.

Despite Sonny’s interest in the interaction between art and politics, he is not dogmatic about the role of art. When I ask if he views art as having a responsibility to challenge power and provide alternative viewpoints, he protests flatly: “No, I wouldn’t go that far.”

Art can be pro-system, says Sonny. After all, if we serve as gatekeepers to the world of art, we will, ironically, be replicating structures that dispossess the poor while enriching the privileged and powerful.

“I do [political art] because it’s my interest. But if someone has no interest in it, you can’t say they’re not doing art,” Sonny reiterates. “They’re not doing political art, for sure. They’re not doing the kind of art that you and I might like. But it might appeal to other people.

“Like … A Michael Bay movie,” Sonny offers as an example, before realising his mistake.

“Maybe that’s not art,” he says amidst our laughter, “but I’m sure there are good adventure stories that are not Michael-Bay bad, not political, and still good.

“Art is more open than that.”

The closed framework within which art in Singapore operates, however, has created conditions that allow only certain types of artist and art to thrive or simply exist. At the most fundamental, it’s a numbers game. As Sonny mentioned earlier in our interview, Singapore does not have a critical mass of people who regularly consume—and pay for—art, so being an artist in Singapore is especially tough, financially speaking.

To Sonny, this has led to a worrying trend in which only art funded by NAC, or art by artists from “at least middle-class backgrounds”, finds expression. These two factors preclude people belonging to lower-income backgrounds from being in the arts.

Sonny speculates: “Maybe people who are in that lower income group are the most willing or have the most reason to critique the system. But they can’t get grants for that, and they can’t take a financial risk because they have to worry about feeding their parents and themselves. So there is a danger where we end up losing those voices.”

Liquid City, an anthology of Southeast Asian comics edited by Sonny, is his attempt at carving out a space for suppressed voices to speak.

Another is New Naratif, an online publication on socio-political affairs co-founded in 2017 by Sonny, Kirsten Han, and Thum Ping Tjin (PJ), whom Sonny met while conducting research for Charlie Chan.

Sonny envisioned New Naratif as an online, medium-agnostic version of Liquid City: “In the beginning, I was interested in New Naratif as a general platform. I was hoping that it’d be a lot of comics, a lot of videos, and music even …

“I think the political side was more PJ and Kirsten’s angle. PJ’s main frame of reference [for the direction New Naratif could take with art] was The Nib, a platform that does mostly politically inclined cartoons and good explainers.”

But, as Sonny pointed out, his views on art are not doctrinal. He believes that all art, whether of political bent or not, deserves to be spotlighted.

Yet, in its current incarnation, New Naratif seems less like a platform for art than activism. Sonny’s “About” section is scrubbed clean of any mention of his co-founder status. In fact, if it weren’t for New Naratif’s republication of Sonny’s comics, I would be hard pressed finding traces of his fingerprints on the site.

Sonny clarifies that he had the freedom to bring New Naratif where he wanted it to go; it didn’t arrive at his imagined destination purely because he “didn’t have the bandwidth to push for his vision.”

“To be involved in New Naratif is a full-time thing. You have to devote the kind of time and energy that PJ and Kirsten put into it. And even Kirsten has left as Editor-in-Chief because she wanted to do her own writing,’ he explains.

“I’m not involved in the day-to-day decisions anymore. I’m more focused on my own projects … My link now is just sometimes contributing art to them.”

With a sheepish smile, Sonny admits that he doesn’t even read New Naratif daily—nor any particular news site, for that matter. So he “has no idea what is happening with the recent PJ thing”.

“I’ve been busy packing, moving … my personal life and projects have taken over of late,” Sonny concludes.

Coming from anyone else more well versed in the world of public relations—e.g. an influencer with an alliterative name or a YouTuber who makes videos about the three types of Singaporean students—I would have seen these pronouncements as smoke and mirrors.

But Sonny seems, to me, to care little about public perception, instead devoting most of his attention to his art and his family. (Sonny chose Jalan Batu as the location for his new studio because it’s located near his old one at Goodman Arts Centre, from which his father would walk home in the evening whenever he visited Sonny; after our interview, he went on an IKEA shopping trip with his mum.)

Even the fact that he is Singapore’s most decorated cartoonist doesn’t seem to leave an impression on him.

When asked what he thinks his role is in the local comics scene, he ponders: “My role ah?”

He pauses.

“To draw comics lor,” he replies, then bursts out laughing, as if that were the most confounding question anyone has ever asked him.