Back in early January, just a few days into the New Year, Koh Seng Choon, founder of the Singapore-based social enterprise Project Dignity was in Hong Kong when he realised that something was about to go horribly wrong.

Covid-19 was still called the Wuhan virus back then, the cases being largely ‘contained’ in Hubei province. Call it sixth sense, or a survival instinct honed through years of hardship, but Seng Choon had seen this movie before. Whatever was coming down the road was going to kill a lot of businesses.

So he sprang into action.

First, he took out a low interest loan for HK$2.1m to bolster his cash reserves at Dignity Kitchen Hong Kong, a hawker centre run by the physically and mentally disabled. When he flew back to Singapore, he borrowed another S$300,000 for Dignity Kitchen Singapore. In a crisis, cash was king. Whatever reserves he could build up today would buy him and his staff months of valuable time.

“Looking back, it wasn’t such a good rate,” says Seng Choon. “Because now the interest rate is even lower.”

In many ways, Seng Choon has always been a little too early. In 2010, he pioneered the only hawker training model of its kind in Asia, that focuses on skilling the disadvantaged in food service jobs. Rejected by the government for grants due to ‘lack of experience,’ he set out on his own to do some good.

And the price he’s had to pay for this was pain.

What Kind of Masochism is This?

As a social enterprise, Seng Choon and Project Dignity have been toiling away for over a decade, stuck in a weird purgatory between a for-profit business and a charity.

On the surface, Dignity Kitchen, a hawker center in Serangoon run by physically or mentally disabled workers, operates like any other F&B business. Yet, Seng Choon measures success not by the profits the business earns, but the number of disadvantaged staff he trains and places in food service jobs, including the 126 people he employs at his Dignity Kitchens in Singapore and Hong Kong.

At the same time, Dignity can’t accept a single dollar in donations for itself, while doing work comparable to many charities.

Even if he survives this pandemic, Seng Choon’s morning routine will never be featured on Business Insider. When he ‘succeeds’, if such a thing is possible, few Singaporeans will notice.

All he gets from surviving today is another chance to survive tomorrow.

So why does he do it?

This is the question that has at turns, confused and troubled me for months, after interviewing him on several occasions—both pre- and post-circuit breaker. Seng Choon is one of the most optimistic people I’ve ever met. Always ready to crack a joke in the face of economic pain that would cripple the hardiest entrepreneur.

“I know what you’re going to ask,” says Seng Choon when we first sat down back in February, “so let me answer them for you.”

He rattles off the questions by heart.

“Am I religious? No. Do I receive any special government funding? No. Does someone in my family have a physical or mental disability? No.”

He places both hands on the table, palms upward, in a gesture halfway between a statement and a shrug.

“I could have walked away at any time.”

One Dignity Day

The origins of Project Dignity goes back to 1994, with a search for Singapore’s invisible people.

An engineer by training, Koh had moved back to Singapore from the UK. Having travelled extensively around Asia, seeing the homeless huddled beneath Tokyo’s underpasses and the beggars outside Taipei’s temples, he wondered why such scenes didn’t exist in Singapore.

So he went looking.

“Let’s just say you can find them if you care to look hard enough,” he says.

“I was running my own business back then, helping companies expand into the Chinese and Indian markets. Helping rich people grow richer. So I decided that for one day a month, I’d go out and do a good thing. I called it my “Dignity Day.””

Some days, he rented a bus and took the elderly from nursing homes out for the day. Other times, he volunteered at Yellow Ribbon, a program that seeks to give ex-offenders a second chance at life through entrepreneurship.

The idea of a hawker training school for the disabled didn’t emerge until 2006, when he met Tony, a polio-survivor with one functional hand and a dream of becoming a chef.

To test the idea of a hawker school, Seng Choon remortgaged his office for S$200,000 in 2010, and opened up the first Dignity Kitchen location in Balestier Market. Tony became his first trainee / graduate, and is now retired with his dream fulfilled.

The Innovation Years

The early years of Dignity Kitchen proved that if entrepreneurs have the courage to take risks, while accepting the chance of failure, they have the power to make a real impact on peoples’ lives.

The only obstacle is the willingness to try.

Because if training a regular person in a food service job sounds tough, imagine instructing a classroom where one student is blind, another bipolar, and another who could have an epileptic seizure at any time.

And yet to reduce these individuals to their disabilities means that they will always be kept separate from the public, dependent on our charity during the best of times, and the first to be forgotten during the worst.

“Instead of focusing on their disabilities,” says Seng Choon. “We focus on their abilities to contribute as individuals.”

First, Seng Choon had to assemble a team of trainers and employment officers to work with students with different needs. He modified kitchen equipment in his hawker stalls. For example, a noodle prep station for a one-armed cook. He made a sign language ordering system for the deaf. He trained the blind to recognize bills by feel so they could work as cashiers.

During the first two years of trial and error, he lost S$700,000. Even after the business started to turn a modest profit, rent increases drove him out to a second location in Kaki Bukit. Rejected by the government for grants, he borrowed an additional S$500,000 from friends.

Hitting Rock Bottom

Just as the second location began to show signs of success, the rent increased again, driving Dignity Kitchen to its third and current location by the Serangoon MRT station. The struggle to get funds to pay the hefty deposit on a new lease also marked the lowest point in Seng Choon’s life.

“When you need to borrow money,” he explains. “You realize you have no friends.”

Around that time, his mother passed away. The small inheritance she left him was enough to secure the lease and get the business running again.

“I cried as I signed the lease in front of her altar,” he says. “But I knew it was what she would have wanted.”

As business slowly picked up at the new location, members of his staff, some of whom have stuck with him for over a decade, approached him and volunteered to defer their salaries, or to be paid in installments.

“People have eyes. Over the years, they can see,” he says. “If you always do what you say you’re going to do, you earn a good reputation. With that trust, I was able to survive.”

‘The Last Three Months Have Been Good For Us…’

I spoke with Seng Choon again a week ago, following the lifting of the circuit breaker measures. It’s been nearly three months since we last spoke. Recently, Singapore announced the Phase 2 reopening on 19 June.

Like other F&B businesses, Dignity Kitchen has been hemorrhaging cash. The hawker centre and training kitchens have been closed, which means no customers. Most of his disabled staff have had to stay at home. For his staff with autism or Down syndrome, the circuit breaker period has been especially tough.

But Seng Choon’s foresight back in January has meant that all of his staff have been paid full wages over the past 3-4 months. No one was laid off. The four stimulus budgets announced by the Government have also helped to cushion the blow.

“My people are special,” says Seng Choon. “This means the toughest challenge for us is to keep my staff active by giving them something to do.”

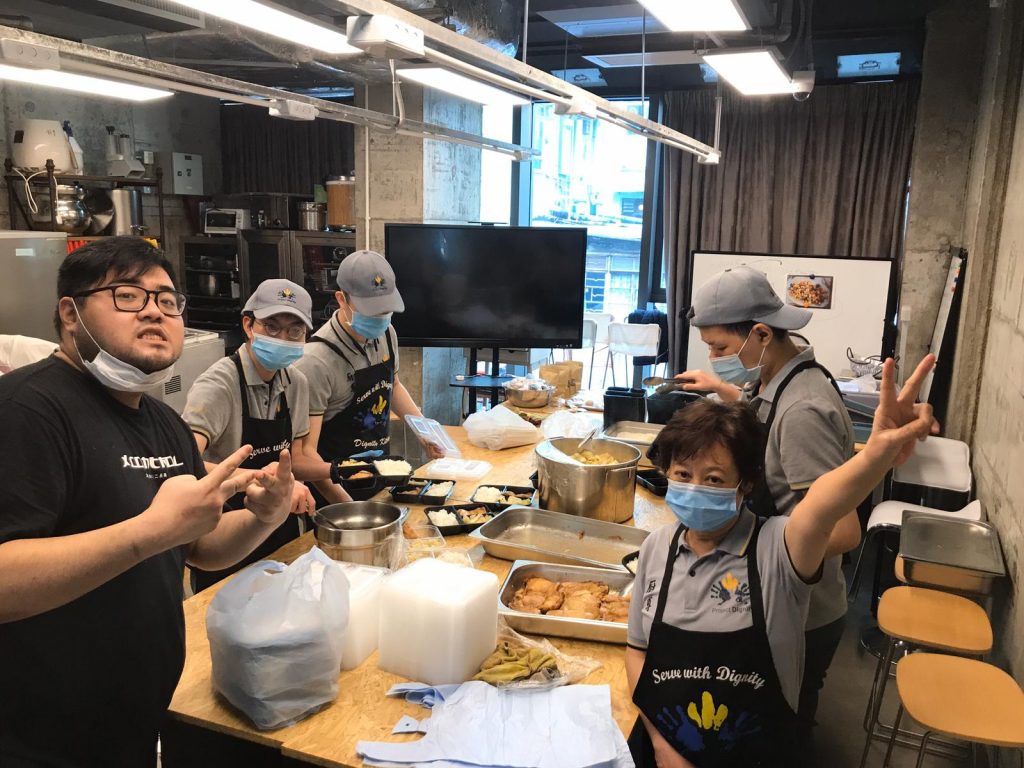

During the circuit breaker, he and his staff have pivoted to a delivery model. Together, Dignity has been supplying an average of 1,000 bento boxes a day to hospitals, nursing homes, and migrant worker dormitories.

“These last three months have been very good for us…” Seng Choon begins.

I couldn’t believe my ears. Very good? In what universe!? No customers. Losing money. Staff with special needs. But Seng Choon carries on:

“The circuit breaker has given us time to rethink everything: from moving our special needs training classes online to trying out other digital initiatives. We’ve rolled out an app called the One Dollar Ninety Nine project, that teaches poor people how to cook healthily for cheap. If you ever go to the homes of poor families, the one thing they all have is instant noodles. Everyday they eat instant noodles. The app tries to educate them on how to cook healthier.”

“Project Dignity also plans to be a job creator for special needs students,” he says proudly. “We are a very unique project in that sense.”

Seng Choon’s optimism is contagious. It comes from a place of both hope and despair. Hope for the future, yes. But despair in the realisation that things are bad enough already. It can only get better from here.

“Will I survive? The answer is yes. I’m wounded, but I will survive.”

The Success of Survival

“From ages 0 to 25 you learn, from 25 to 50 you earn, from 50 onward you try to give something back. Try to pass things onto the next generation.”

“As they say in Chinese about money,” Seng Choon continues. “生不帶來 死不帶去. You don’t bring it into this world, you can’t take it with you when you go.”

For Seng Choon’s part, he’s always looking to the future. As the only hawker-training model in Asia, he has plans to scale Dignity beyond the recently opened Hong Kong location, even as a year of city-wide protests and Covid-19 have dealt the project a double blow. To the outsider, this may seem like masochism to the nth degree. Or maybe it’s just a finely honed survival instinct: stop moving forward and you die.

Everywhere he looks, Seng Choon sees young people willing to carry on his work.

“I’m almost 62 years old. Don’t have much more time or energy to do this. But I’ve built a good team around me who can carry on.”

Once again I pose the question: does he ever feel like walking away?

“During the toughest years, almost every day I wanted to quit. But I couldn’t. There were people who depended on me. My staff. My students. Not just them – but their families.”

To Koh Seng Choon, the survival of a community is a different kind of success. Something that will never get the attention it deserves.

For Project Dignity, doing good will have to be good enough.

And if that’s his definition of success, then what’s failure?

“Failure is when you stop trying.”

Dignity Kitchen is located at Blk 267 Serangoon Avenue 3 #02-02 (click here for directions). Starting October 2020, they will move to a new location at 69 Boon Keng Road near Bendemeer Market.

With the Phase 2 reopening, please pay them a visit. A dollar spent here would be a vote for a more inclusive society. A place where individuals with disabilities can transcend their labels.

Other ways to support Project Dignity:

1. Dignity Kitchen offers bento boxes for delivery via their website. Click here to order.

2. Sponsor a meal for the elderly

3. Sign up for an online class via Skillsfuture: Dignity Kitchen offers cooking and baking classes, and a chance to learn from certified special needs trainers

4. Follow them on Facebook for the latest updates on the Phase 2 reopening

Want to sample Dignity Kitchen’s famous rojak or their claypot rice with wok hei? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co. Or better yet, visit Dignity Kitchen during Phase 2. This article was not sponsored.