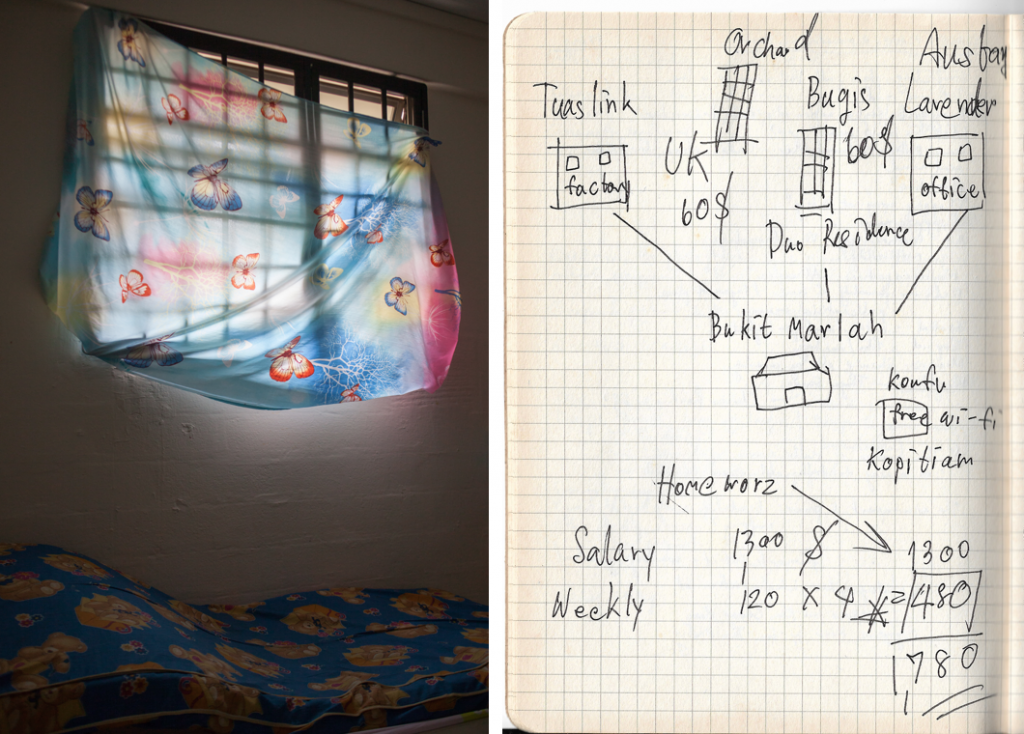

Above, Wiyada in front of her window in the shelter where she stays with her two children.

It is 6 AM. I stir from the living room couch that has been folded out into a bed, to find Mirriam already up and getting ready to go to work.

The rest of the house is silent. Her three sons are still asleep, occupying the two bedrooms in the apartment that she rents from the open market.

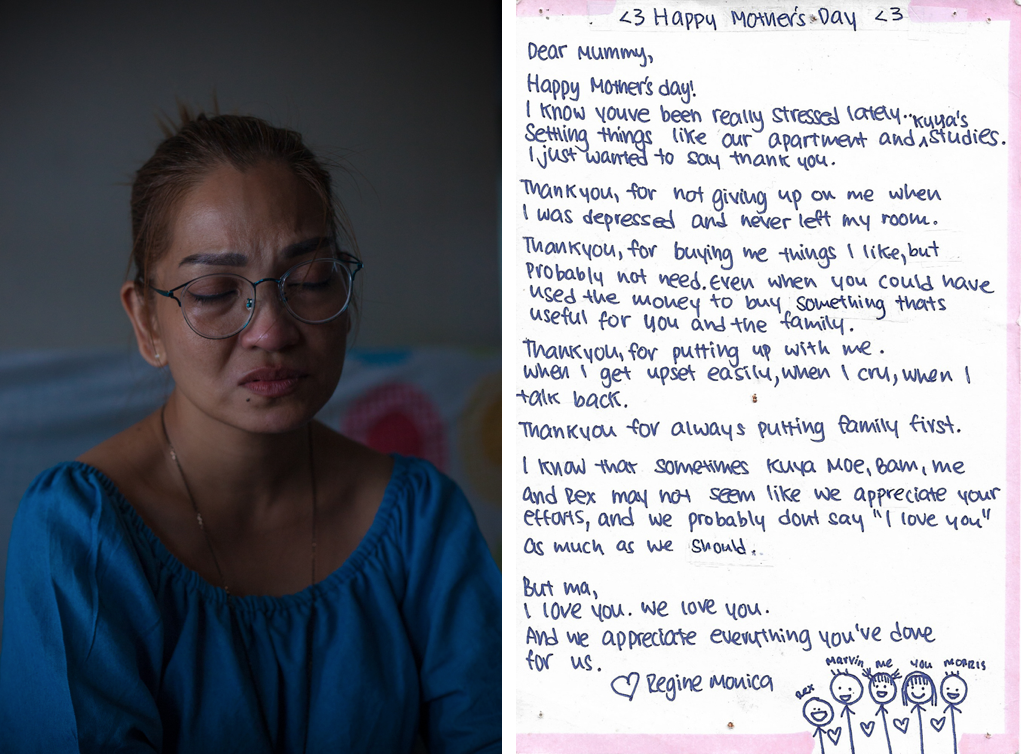

Six days a week, for 14 hours a day, Mirriam works in a bakery on Orchard Road, opting for as many over-time (OT) hours as she can. At around 10 or 11 PM, she returns home—as of now—an expense she can barely afford.

Often, her appointments require her to take time off work, which means even less money for the month.

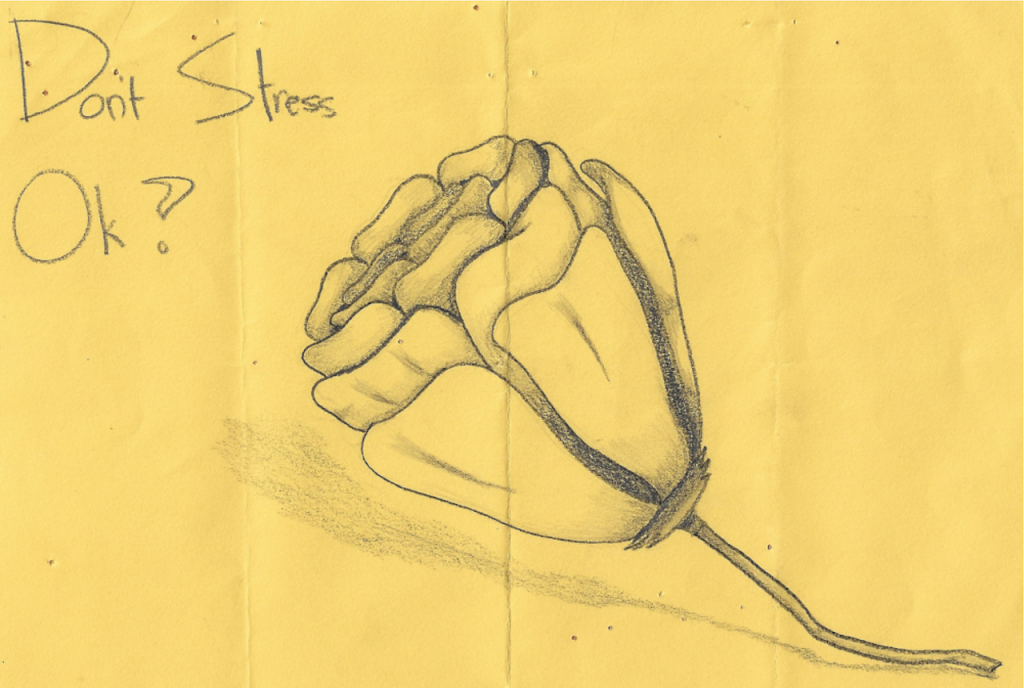

“The stress is taller than me,” she says, her anxiety palpable.

Her situation is not uncommon amongst the few women I have been profiling, all of whom are single mothers.

For those who qualify as low-income earners, there is the anxious pursuit of better jobs to provide for their family, leading to unstable, often changing work environments. This seems to result from a combination of different struggles: the desire to spend more time with their children versus the need to earn more, the mental stress of their precarious positions; their lack of educational qualifications for higher-paying positions. All play a part in their decision-making process, which is often about the immediate rather than the long-term.

For those whose priorities are making ends meet from month-to-month, long-term planning is a luxury they literally cannot afford. Those who are not Singaporean citizens also face the added pressure of cultural and linguistic barriers that make it difficult for them to navigate Singapore society.

Suparmi, for instance, is a young Indonesian widow who has worked in a range of jobs, from selling food in a food court to being a patient transporter at a hospital. Like Mirriam, she works six days a week, spending her remaining hours at home with her two young daughters.

In one of the richest cities in the world, who do we see, and who remains invisible?

Its key recommendations included increasing the $1500 income cap for rental housing, lifting debarment periods for rental housing and HDB purchases, and treating an unmarried mother and her children as a “family nucleus” for HDB schemes. In March 2018, the government lifted debarment periods, such that divorcees can now purchase or own a subsidised flat immediately after their divorce, without having to wait three years.

However, other challenges remain.

The Home Ownership Plus Education scheme, for example, allows for rental subsidies, but limits the primary caregiver’s salary to SGD1700 to provide for the household (including one or two children).

The Assistance Scheme for Second-Timers applies to divorced or widowed parents, but requires parents to sell their matrimonial flat before the divorce. At the same time, parents—particularly mothers—who are lowly educated and/or unable to find consistent employment while taking care of their children, have found it difficult to apply for this scheme.

Likewise, unwed mothers are not allowed to purchase an apartment until the age of 35, as they fall under the Singles scheme. These are just some examples of caveats in public policies which make it even more challenging for single-parent families to navigate the system.

Currently, the HDB makes allowances on a case-by-case: a legislative precariousness that some might term a power play, simply because the authorities can decide on a whim or on seemingly arbitrary factors.

This reluctance to demonstrate full support can be linked to the government’s stance on family units. In 2016, after making several policy changes to benefit single mothers, including extending maternity leave to 16 weeks and allowing children access to a Child Development Account, Minister Tan Chuan-Jin stated that the benefits do not undermine parenthood within marriage, and that the government continues to encourage this prevailing social norm.

In the meantime, low-income single parents and their children continue to bear the brunt of not fitting into the nation-state’s ideal of what a family unit should be. Their need for space, in particular, is felt even more acutely.

This is What Inequality Looks Like, Teo You Yenn

In my time with various single parents, I often ask them to draw me a map of where they spend their time.

For Widaya, most of her time is spent shuttling between the offices and homes that she cleans, and her own, a temporary shelter that she shares with her two children. The only other place of regularity is the nearby Koufu, which offers free Wi-Fi for her children. In addition to free entertainment, the presence of the food court’s patrons and workers often mean that there are more watchful eyes over her children as they sit there after school, waiting for her to finish work. It is the only form of babysitting she can afford at the moment. This space, simply transitory for many others, is a safe haven for Wiyada and her family.

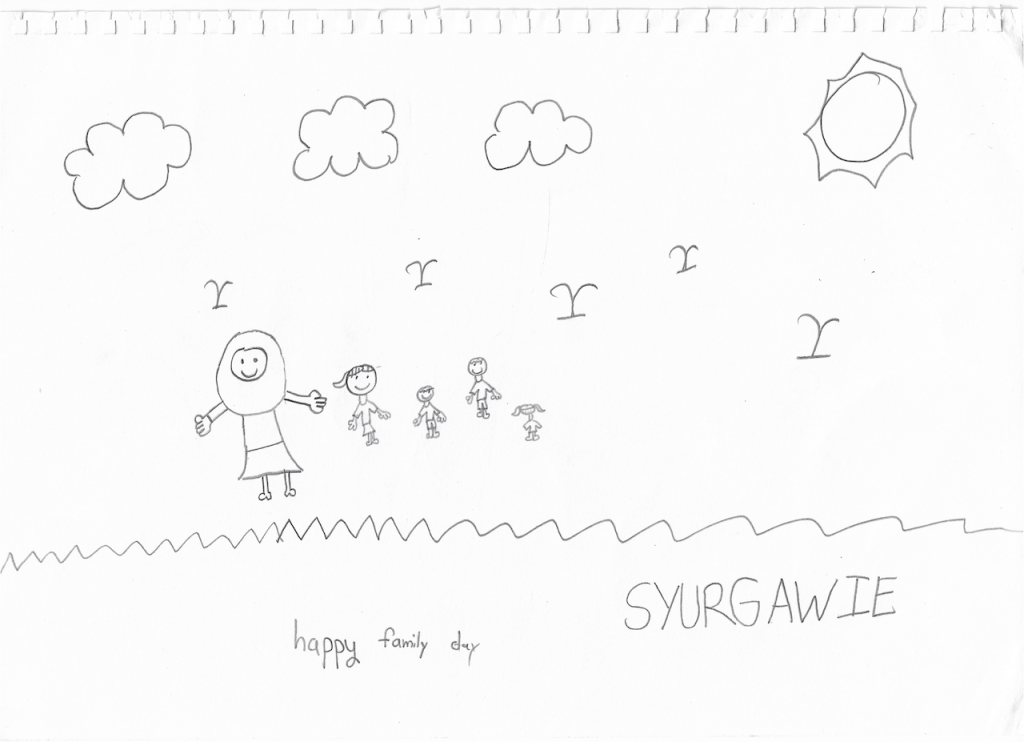

When discussing spaces of leisure, many of the single mothers mention parks or beaches, where they don’t have to spend money and meals are often home-cooked and packed for a picnic. Shopping malls are often out of the question; the pressure of having to buy new items for their children, and the potential tantrums that might ensue, are not incidents they wish to have to handle.

On one occasion, Yati, who recently separated from her husband, explains that she has never been to the Singapore Zoo despite having lived here for a decade. She and her two sons sleep in the living room—she on the couch, her sons on the floor—while her husband sleeps in the sole bedroom.

Wiyada and her two children occupy one room in a two-room shelter, which means a frequent rotation of neighbours and new strangers who she has no choice but to try and co-exist with. After all, it is still a better option than the previous shelter she stayed at, where she saw women practising prostitution as a trade.

After being kicked out by her husband, Mirriam first spent nights sitting at Yishun Park trying not to fall asleep for fear of crime or harassment, before taking the first bus to Changi airport where she had a job in one of the restaurants. It was at the airport that she snuck in naps before her job began. Eventually, one of her employers found her sleeping, questioned her about it, and referred her to help.

When public space can become the best option for dwelling, it becomes almost impossible to imagine living in a space that is not only tolerant, but encouraging and nourishing.

In a 2018 report by the Institute of Mental Health, it was noted that single mothers have a higher risk of mood disorders. In my encounters with Mirriam, she often breaks down, having just recalled a particularly frustrating time at home, work, or in court. Yet due to a lack of money and time, counselling is not an option she considers.

In addition to the everyday responsibilities that come with caring for and nurturing young human beings, single parents often find that the basic right to space, even if insecure and transient, is only obtained after an uphill battle. Alongside policy recommendations that deal with the logistics of improved housing policies, the emotional toll of living this way is something that a society must also take into consideration when drafting policies to bring all its members forward.

“[I want] to make this house like a castle,” she tells me.

To make this house like a castle; to make the best out of every situation they have been given, displays a resilience that I encountered among all the parents I profiled. Yet don’t the most vulnerable among us deserve more than making do?

Spatial justice is an issue that has been in the limelight in recent years, as issues of urbanisation become more relevant to more members of society. It is found in the writings of David Harvey, who famously proclaimed that the right to a city was about how each individual had the “right to change ourselves by changing the city more after our heart’s desire.”

If it is in these mothers’ desires and best interests to provide the most adequately for their children, then the spaces they inhabit must reflect this as well.