There are parties, and then there are eight-day-long parties filled with fried food, games, and presents. I have never been to one of the latter before, which is how, on the second Sunday in December, I find myself standing by the gates of the Chesed-El Synagogue, waiting to join the congregation for their final Hanukkah event of the year.

Hanukkah, a Jewish holiday also known as the Festival of Lights, commemorates the success of the Maccabean Revolt, a military campaign launched by a group of Jewish rebels to reclaim Judea, now modern-day Palestine, from the Selucid Empire in 167 BCE.

Upon recapturing Jerusalem and reclaiming the Second Temple, the Maccabean rebels found only one jar of oil in it—barely enough for a night’s ritual use—but the single jar kept the temple’s lamp burning for eight days and nights. Nearly two millennia later, these events are celebrated by Jews the world over as a symbol of the endurance of Jewish identity.

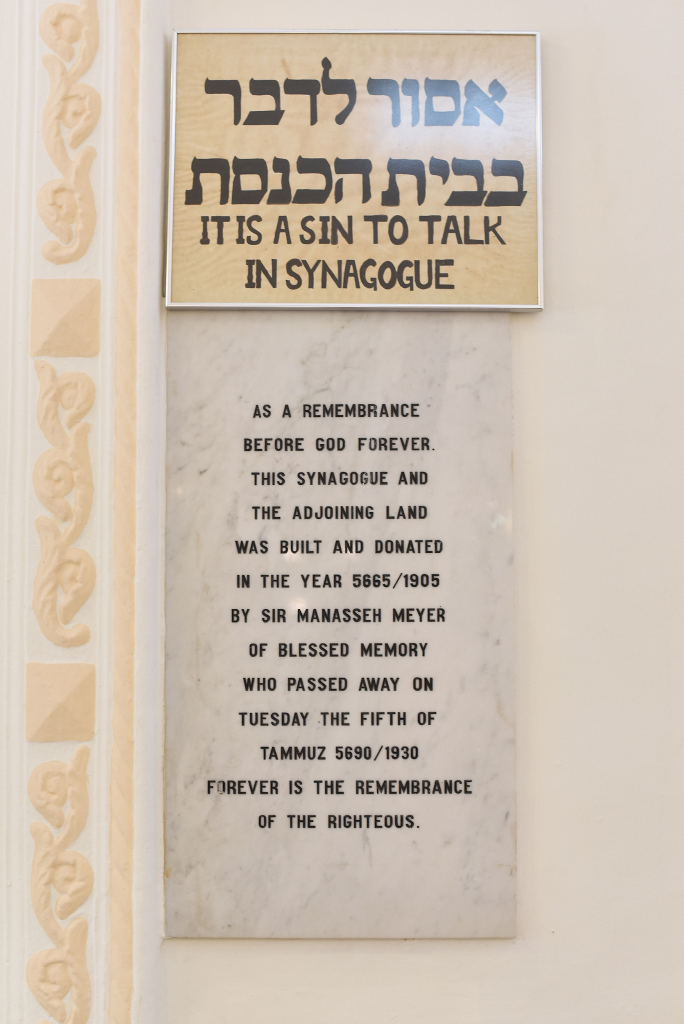

The Chesed-El Synagogue, tucked away in the hilly neighbourhood of Oxley Rise, is the second of two synagogues serving the local Jewish community. The first, the Maghain Aboth Synagogue in the traditional Jewish quarter of Waterloo-Middle Road, was built by Sir Manasseh Meyer, a Baghdadi Jewish merchant, philanthropist, and community leader, in 1878.

When the community grew too large and fractious for one synagogue to accommodate, Sir Meyer commissioned the building of the Chesed-El, which opened in 1905.

We arrive at the synagogue early, and the building is nearly deserted. Apart from a stack of paper plates and soda bottles by the entrance, there’s little indication of the festivities to come.

With only one or two guests around, we take the opportunity to roam the building. The rain which has plagued most of December has subsided; this afternoon, sunshine comes streaming in through the windows, bathing the synagogue’s Palladian architecture in light. The sight is breathtaking, and I find myself wishing that I didn’t have anywhere to be or anything to do except drink in the silence.

I make my way over to the tentage in the synagogue’s yard, which is set up like almost like a condominium’s function room, complete with adjoining kitchen. Inside, around 30 to 40 children, from toddlers to 12-year-olds, their parents trailing behind them, have gathered for the kids’ programme.

Tables are scattered with colour pencils and crayons for a colouring contest, as well as bowls of crisps and multicoloured dreidels (a small four-sided top, beloved by children at Hanukkah parties). An event team has been hired to help the children craft DIY acrylic keychains of their own design, and a foosball table has been set up in the middle. Someone tells me the grand prize is an iPad.

And then, to my surprise, I see a Chinese face in the crowd.

For Joseph, who discovered Judaism around five or six years ago, Hanukkah is a time to celebrate with the rest of the community and educate his three children on the significance and history of their faith.

“In our lives, we have our highs and lows,” he tells me.

“And sometimes, we can get very low … we end up in those very deep valleys where we can’t even breathe. It can be because of relationships, finance, or health—there are many reasons. But this time of year, this is when we believe and we pray, because good things do happen. Miracles do happen.”

Pressed for what he means by miracles, he ventures, “There are natural miracles, like rain, the colour of the sky, why we have wind. And then there are the other kind of miracles, when people do things for each other, even when they’re busy or going through crises themselves. This is what the Jews believe in, and it’s beautiful.”

This sentiment is echoed by Maggie, whom I meet by the synagogue’s entrance, not long after I flee the crowds of children for the safety of the drinks counter, where most of the adults have gathered. Maggie, 35, who was born in Shanghai and converted to Judaism upon marriage, moved to Singapore eight years ago, and is attending the festivities with her husband and their three children.

As she tells me how she has found meaning in her faith, she speaks slowly and carefully, with an intensity that takes me by surprise, “People can get very concerned about material things. Whether you have a car, condo, that sort of thing. But faith feeds your soul, not your wallet.”

Meanwhile, over at the food table, Aviv, an Israeli Jew who runs a restaurant in Suntec City, is put out about the lack of jam in the sufganiyot (donuts). “I’ve had two, but I don’t know why there isn’t any jam in them. I was looking for the jam, you know?”

Sadly, by this time, the latkes, a kind of potato pancake similar to a mini potato rosti, and a staple of Hanukkah feasts, are all gone. Apparently, the appeal of fried potatoes transcends all religions and cultures.

I take my plate of food and drift between the entrance and the synagogue’s main hall, where the adults are mostly chatting in groups. A few boys have wandered over from the children’s tent and have taken out some religious texts for study. Before long, a couple of men come over to join them, guiding them through the Hebrew passages.

To that end, while it’s ostensibly open to the whole congregation, it strikes me that it’s the children whom the event is really for. Their parents have brought them here for something much larger than a single afternoon of fun; it’s over these tables of games and party snacks that they – the future of the community, as Rabbi Fettmann remarks to me with obvious pride and affection – will learn to look at each other and recognise their kin. In the midst of this, I can’t help but feel like an interloper.

In the middle of my ruminations, I bump into Anthony and Tania, a British couple I met earlier on in the children’s tent, who are attending the party with their young daughter and five-day-old son. The couple, who look remarkably relaxed despite the sleeplessness of new parenthood, tell me they haven’t even given their boy a name yet. They are waiting for his brit milah (circumcision) ceremony, to be held the following Wednesday.

They invite me to attend, and then, apropos of nothing, ask if I would like to hold their son.

Their trust and openness astonishes me; they barely know me, after all. But when Tania passes her son’s warm weight into my arms, and his little fingers curl around mine, I find myself feeling a little less out of place.

Half-eaten bourekas are left on plates, drinks are abandoned in their cups, and children are slowly shepherded back into the main hall while their indulgent parents trail behind them. Once everyone has gathered, Rabbi Fettmann announces the young winners of the various competitions, to the crowd’s obliging claps and cheers.

When I leave, the candles are still burning.