Top image: Nick Karvounis/Unsplash

A year ago, while conducting interviews for a series on LGBTQ+ Singaporeans, a question kept churning in my mind: where are all the older people?

Ageism exists across society, and is in no way limited to the LGBTQ+ community. But combined, the two produce a startling vacuum. Older LGTQ+ people are a minority within a minority, which is to say they are practically invisible. Even most of my LGBTQ+ friends, when asked to help me find leads I could interview, couldn’t come up with a single name they knew personally.

Older people’s stories generally don’t get a lot of screen time, but the ones that do are more or less exclusively heterosexual. Representations of contemporary queer life, from films like Blue Is The Warmest Colour to TV shows like Orange Is The New Black and Queer Eye, largely show people in their 20s and 30s. And the Internet, which has been instrumental in increasing LGBTQ+ visibility, with many brave coming-out stories and personal essays about LGBTQ+ lived experiences, is unquestionably the domain of the young.

But clearly, not all queer people are young, and not all queer stories are, either. We spoke with three LGBTQ+ Singaporeans in their mid-50s and above, who graciously shared theirs with us.

Jeremy*, a cisgender gay man in his early 60s

I guess you could say my very first exposure to queer culture was when I went to the Philippines in 1981. You know how Singapore is, it’s not touchy-feely, we don’t hug, no way two men would be hugging or kissing each other.

I was 21 at the time, and when I got there I was like, is everyone gay here? To see men holding hands, hugging … it wasn’t that they were gay, their culture is just so warm and physically affectionate, but it seemed that way to me. I found the lack of labels so liberating, to see how they were so intimate and yet it was a non-issue.

Growing up, there were no examples of gay relationships at all. At the time, ‘gay’ just wasn’t in our vocabulary, it didn’t exist back then like it does now. When I was young, it used to mean happy, bright, bonny, good.

I grew up poor, in a traditional Peranakan household, and culturally I was in a desert. A lot of my education came from a dear friend of mine, my mentor in life, and in gay life in particular.

We used to watch videos at his house, and one of the ones which left an impression on me was Making Love (1982). It’s about a couple where the husband falls for another man and embarks on an affair. What really struck me was that the wife found out in the end, and they had a huge fight and she slapped him across the face—she goes, “I can fight with another woman, but how could I fight with a man? How could I compare?”

[The film ends happily], but watching this scene, I was like, oh god. Is this how it is? Most films about gay people are terribly depressing. It never ends well.

As a gay boy back then—and even now, I think—when you’re young, a lot of it is about sex and getting off. When you don’t have mentors to look up to, or examples of healthy, mature, gay relationships, you just think it’s all based on sex and will never last. I’m not sure this has changed much now, although hopefully it’s a bit better. Still, examples of gay men in solid relationships are so invisible.

Acceptance can only come when there’s deep and abiding love. Everyone just wants to be treated with respect and love, and that only comes with honesty. If you’re not honest with yourself, there’s no relationship which can be sustained.

I’m not out to my family, but only because they’ve not asked the question. Otherwise, it’s an open secret. My siblings have met my partners over the years, and I guess they just accepted it. My mum has passed on, but when she was alive she knew all my boyfriends’ names … she would go, oh, so-and-so isn’t staying with you any more? Are you not friends any more? I think they’re just waiting for me to come out to them, and I’m waiting for them to ask.

Right now, I have everything I need. I’m in a happy relationship, I have my own flat, my dogs, and I don’t want children. The one thing I would want to change is end-of-life rights. Otherwise, my sexuality is right at the bottom of my interactions with people. It doesn’t present any issues now.

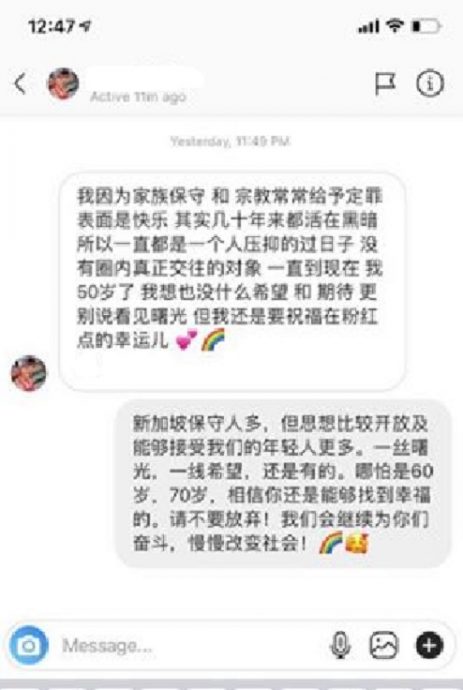

My partner loves Pink Dot. He’s much younger than me, and he goes every year. I go because he loves it so much, but I’ve been through all that, and I don’t need that kind of affirmation or public platform of support at my age.

But I’ve been very blessed, with the friends and family I have, and working in arts and entertainment all my life. The scene is so much more exposed and accepting. If I hadn’t, I shudder to think of what my life might have been like.

Linus*, a cisgender gay man in his early 60s

I guess we all had inklings…you know, the dance of hormones, feelings you have as a teenager. So I went to the library in school and looked it up.

We had a great library. Lots of texts on sociology and bio, and there was a book called ‘Everything You Want To Know About Sex But Were Afraid To Ask’ (I think one of the very young teachers was heading up the library at the time). Once I identified what I was, internally, it was easy. I didn’t struggle with it, unlike some friends and classmates I knew.

It was never an issue with my siblings. But my dad didn’t know—he passed away when I was in my 30s—and my mum doesn’t know. I don’t think she even knows what being gay is, and it wouldn’t be possible to explain to her now because she has dementia.

I never thought of telling her when I was younger. My parents are so steeped in the older concept of what being gay is, she’d probably just assume that it’s someone who cross-dresses and wants to put on women’s clothes. It was never something I thought of attempting.

When I got older, there were chats on the Internet, stuff that I guess would be the equivalent of Grindr or Tinder nowadays. There were saunas, where men went to have sex with other men. And there were bars and clubs like Inner Circle, Taboo, that you went to … but most of them don’t exist anymore. In any case, the club scene is very much geared towards young people. As you get older, it stops being so enticing. You look like a sad fish out of water.

I think we were only conscious of the AIDS crisis because so much was happening in America. We read about it in the papers and in books, but I think we in Asia tended to think of HIV as a ‘Western’ disease. It was scary, but by the time we realised this was happening to us, there were already medical discoveries and organisations like Action for Aids (AFA), so there was greater awareness, and anyone sensible knew to take precautions.

Still, I have some friends, some close ones, who’ve had it, or died from it. Sometimes you hear stories about someone succumbing to pneumonia, and they’re not that old, maybe in their 40s. And you think: could it have been HIV-related?

It would be a nice victory if 377A was repealed, but I’m not holding my breath. The government will always say that the moral majority is conservative and not open to LGBTQ+ people. Personally, I don’t think there’s an ideal society; my friends and I never thought of going out there and demanding for solutions, because that’s not going to happen.

In my opinion, what one should do is try and look for a way around things, find a personal solution, or you’ll just be hitting your head against the wall. I happen to know one of the couples who challenged 377A, and they told me that after two or three years of slugging it out in court, they looked at each other and asked if it was really worth it, because they ended up exactly where they started. Looking to the authorities for a solution is a tough sell.

But I’m hopeful that things will change gradually. When I talk to generations that came after me, young couples in their 20s and 30s, everyone’s so comfortable with it; everyone’s got a token LGBTQ+ friend they’re so fond of. I’m optimistic that way.

Cathy*, a cisgender lesbian woman in her 50s

Work was lonely. I worked in the corporate world in my 20s and early 30s, and I never saw another gay person. You couldn’t talk about it. Stuff like what you did over the weekend, water-cooler chat … you can’t go into it, and I guess that’s why I always felt like a bit of an outsider. It was never hostile, but you just felt different, and conscious of having to hide in a way which other people didn’t.

I began working in the charity sector and becoming involved in civil society in my 30s, and that was what changed things for me. Before that, for a long time, my plan was to migrate.

When I was younger, I would imagine myself on a farm, enjoying the outdoors and seasons … idealistic things like that. It was only after I got involved in civil society that I began to feel like I was making a difference, and everything changed; it was how I met my partner, too. But I honestly think I would’ve left if I hadn’t found that.

Civil society was an interesting place in the early ‘90s. The organisation I joined was a very accepting space. You felt comfortable bringing people and they would treat your partner as a friend, but no one asked about it, or spoke about it the way it is now, even there. You felt the acceptance, but you never introduced anyone as your partner. I didn’t do that until very late in life.

Right now, I think it’s just a matter of time. I’ve bet with my friends that in 10 years’ time, we’ll be living in a very different society, and 377A will be history. I work with a lot of young people, and it gives me a lot of hope. We’re on the right side of time, and we’re moving towards acceptance. I don’t see how Singapore can keep still.

Still, I’ve been incredibly lucky. Being a lesbian has been tough at points—perhaps not as much as for other people—but I think it compelled me to find my own way in the world, to make sense of my own life, because the tried-and-tested route just wasn’t available to me at all. Having kids, getting married … that’s never been on the cards. Even moving out, which I did at 22, was so radical at the time.

The other thing is the support of my family. My sisters and I are all gay, and we came out to our parents when we were in our early 20s. It was a journey they had to go through, and there were some very difficult years, but that was one of the privileges I’ve had: parents who really, really love me.

Their friends still aren’t comfortable with it, and I guess that’s the difficulty with society as a whole not moving, even if [my parents] have as individuals. They had to give up some of their friendships, or not see their friends so often, because the comparisons their friends were making or asking about our lives … they just didn’t know how to deal with that, and it was very painful for them. They had to have smaller worlds so that we didn’t have to be in the closet.

But a few weeks ago, around Mother’s Day, I had a Zoom call with my mum, and she said, this was my best decision. I was like, what was?

And she said, accepting all of you. That was the best decision I ever made in my life. It was the first time she’d said that.

Names have been changed to protect interviewees’ privacy.

Send us your thoughts on this story at community@ricemedia.co.