“Hi, my name is Anthony. My wife is expecting this year, and I have cancer.”

This was how Anthony Lee introduced himself to me back in 2013. Articulate, well-mannered, and built like a tank, he stood out in the crowd of strength athletes at the table. We were at a Hari Raya party hosted by a mutual strongman friend. Although I was the one speaking directly to him, his casual remarks stunned everyone at the table. The silence was deafening.

What do you say to a stranger who declares he’s marooned between dying and the birth of his first child?

Much later, I asked him how he could have been so nonchalant. He explained that he had wanted to confront his cancer directly and not hide his illness. It helped to reinforce his resolve to stay alive; maybe then, he would live to watch his daughter grow up.

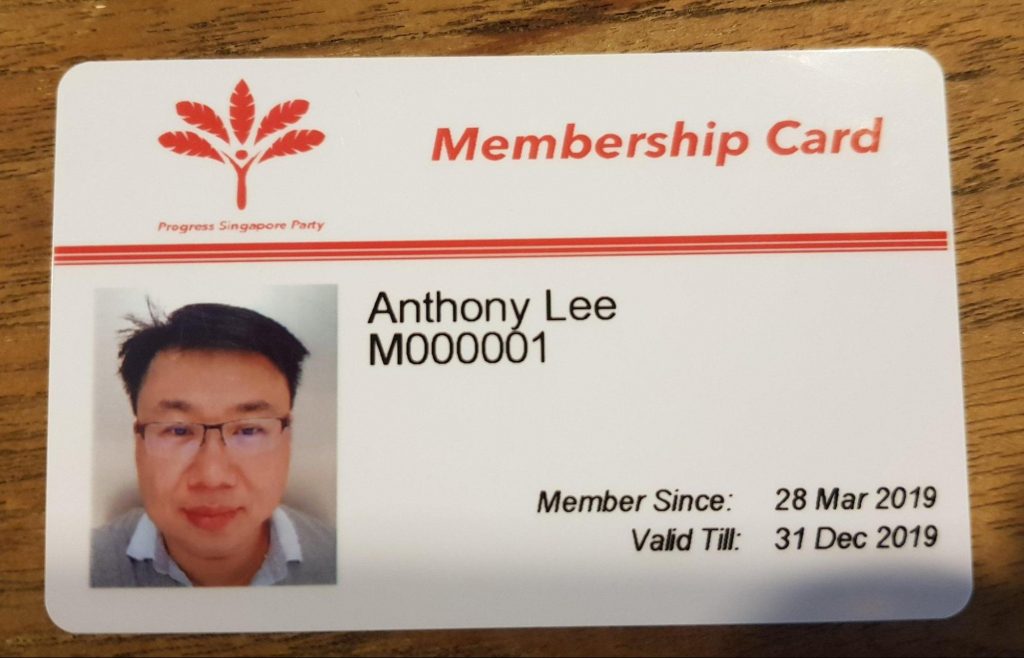

While all of this was happening, he became involved in politics, going from volunteering for Dr Tan Cheng Bock’s Presidential run in 2011 to co-founding the Progress Singapore Party in March 2019.

Just days before our interview this June, this Cockney-speaking giant was discharged from the hospital for severe acute pancreatitis. He may have escaped cancer himself, but one health crisis after next seems to strike either him or his family like an obsessive Grim Reaper.

For better or worse, this series of unfortunate events has been pivotal to his drive to join politics. The turbulence of providing care for his loved ones reinforced his beliefs that something is deeply wrong and inadequate with our country’s system, where there is not enough compassion for the downtrodden.

To understand Anthony’s psychology and political values, one cannot ignore his childhood.

Anthony was the first of two sons, born into a family that ran a business selling coffee powder and doing wholesale coffee bean roasting. The business was set up by his father Lee Kim Tow in 1979.

Anthony began having health problems from a young age. Aside from asthma, he recalls his first traumatic health episode at 10-years-old, which involved him waking up one morning and urinating fresh blood. There was no firm diagnosis on the cause of his condition, but doctors suspected IGA nephropathy, a disease related to the kidneys.

This continued for 7 years, occurring a couple times a year. It eventually disappeared after the doctors removed his inflamed tonsils, deducing that the antibodies were attacking his kidneys.

All this took a significant toll on him as a young primary school student. The weekly hospital visits hurt his grades and disconnected him from his friends.

He reminiscences somberly, “Since I was hospitalized a fair bit, it sort of becomes out of sight-out of mind. There was little support from teachers & classmates. The culture back then was to focus on grades and teachers had limited bandwidth to care.”

Despite all this, he developed a complex to help people at all costs. This was largely due to his upbringing, and he would follow his father, who was a fervent grassroots leader for Dr Tan since the 1980s until Dr Tan’s retirement. Mr Lee assisted in relaying concerns from the ground to Dr Tan, the town council, and HDB, and helped settle disputes between market stallholders and hawkers.

But one mishap after another began piling up. In 1997, he was the unfortunate victim in a street fight—even though he was merely a bystander training at a public basketball court. He was slashed on the right side of his head, and was left with a scar. That was the end of playing basketball. He then moved on to strength training, eventually competing in strongman sports and arm wrestling. Due to an old injury, he eventually shattered his humerus bone (a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow) and suffered nerve damage.

His doctor said,“It looked like someone took a hammer and smashed a piece of glass or windscreen.”

His brush with death would come in early 2013. He had been hospitalised for heart palpitations due to immense stress from starting his pet care business. A cardiologist referred him to an arrhythmia specialist who presumed he had Wolff Parkinson White syndrome (a rare condition when there is an extra electrical pathway in the heart).

While there, he felt an unusual lump on the right side of his face. After doing some research of his own, he became concerned that it could be cancer, and consulted a variety of doctors and an ENT specialist. Eventually, he was informed around late April that it was a case of Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma in the saliva gland.

Although the doctors insisted on operating on him immediately, he resisted chemotherapy and other invasive treatments. His parents were in denial, and he tried not to dwell on it lest it break their spirits. Instead, he continued training at the gym, and started researching his cancer. Determined to beat it, he took on a number of supplements and a great deal of fruits.

He explains, “I never saw my grandfather because he died when my dad was 3. And I can’t bear the thought of not seeing my daughter grow up or history repeating itself where a child is unable to see her parent. We only had her after 10 years of marriage.”

He decided to operate by September so that he would recover in time to take care of his wife in her final trimester.

When I ask him how he felt during these intervening months, he replies, amused, “Actually, I felt normal. And that created doubt in me whether the cancer was in the early stages or maybe whatever I was doing was helping.”

Nevertheless, he went for his parotidectomy (surgical excision of the parotid gland, the largest of the salivary glands) only to receive an extremely dumbfounding outcome. There was no cancer.

He was told that at his age, the odds of dying from this condition were higher than that of getting into a car crash. He could just drop dead at any time.

Anthony knew he had to stay alive for his family. But during the procedure—in which Anthony was totally conscious—the doctor found an abnormality that led him to abort. Later, the doctor explained that he’s only seen 2 cases like this: a benign condition which gives the same reading as the presumed condition.

For a man who has been close to death twice, Anthony has come to terms with the volatility of life. He was initially indignant with the cancer episode, but eventually he made his peace with it.

In what is to become useful in managing oncoming crises, he expounds on the importance of maintaining a stoic mindset: “It’s a natural process. At some point, you won’t be upset when things don’t work out the way you wanted. I worked past the anger and disappointment, it’s a life cycle. I tell myself and others this, don’t ever be consumed by your anger and disappointment or you will never have clarity.”

Other members of his family would meet with their own misfortunes. On October 2014, eight months after the arrival of his daughter, his mother noticed his father was struggling to breathe and move in bed, so they rushed him down to A&E.

The CT scan showed his brain was bleeding. He’d had a massive brain haemorrhage.

At the hospital, Anthony saw his father turning non-responsive and slipping into a coma. The doctor explained that there was a 20% chance of surviving surgery, which involved draining over 100cc of blood in his brain. His father would go on to stay for more than 200 days in the hospital.

Anthony recounts the agony of the experience: “He stayed in the ICU for the first 4 months. I would leave home at 5 AM from Clementi to go Changi General Hospital because I want to get the doctors during their morning rounds as he had up to 7 teams overseeing him … and I get to see how he is. His eyes eventually opened after almost 4 months but they were hollow and glassy, as if there was no soul. Many days I stayed till late, accumulating a lot of expenses from the transport costs including parking.”

There were also the midnight emergency calls telling him that his dad was not going to make it.

During this period, a friend and I met up with Anthony on one occasion. Our friend asked if he would consider taking his father off life support, but Anthony was adamant about hanging on.

I recall his words, “Just one more day makes all the difference.”

Eventually, he was transferred to the general ward. Though stable, there was very little progress. One of the most difficult experiences for the family was deciding whether to resuscitate him in the event that he became moribund. After a family discussion, they decided to sign the Do Not Resuscitate form.

However, when it came to that critical moment, his mother was unable to sign the form, and Anthony could see she wanted to keep him alive. Explaining that they met in their teens, Anthony weeps tearfully, “It felt like I was signing his death sentence. Why I chose to sign it is because I didn’t want my mother to carry the guilt. I didn’t want her to blame herself, so I took it upon myself to do that. It would kill her to carry that blame and guilt.”

His father-in-law, however, was in denial, and began showing signs of depression. To assuage his stress, Anthony took him out for frequent walks to chat. He points out that most people overlook the state of family members who also become depressed when watching loved ones battle cancer. She has since recovered and is doing well.

Throughout all this, the impact on everyone in the family has been immeasurably profound. One poignant regret of Anthony’s was not being able to spend time with his daughter (who was 8 months old at that time), and missing important developmental milestones.

His father still lives to this day, defying expectations of an early demise. It has been 6 years of him being in a vegetative state. Aside from the emotional burden, it has not been an easy transition given new difficulties with intensive home care.

For one, there’s the difficulty of getting sustainable adequate care for his father. He looked into various hospices and homes but found very few institutions that could take him. There is a waiting list for public ones, and the private homes are expensive ($8000 a month excluding items like diapers and medications). Eventually, he settled on training and hiring 2 domestic helpers who oversee every aspect of his father’s health—bathing, feeding and cleaning him.

His mother continues to look for signs of cognition. By now, Anthony says his father’s eyes aren’t as hollow, and can track movement. But he can’t respond to commands like being asked to blink. Contemplating the possibility that there is brain damage in the hippocampus (memory area), Anthony discloses telling his father in the ICU, “It’s ok if you forget me and brother, just remember mother.”

Trying to moderate his mother’s hopes is tricky too.

“I try not to dash her hopes. I don’t know, perhaps it’s possible deep down she knows that recovery chances for my dad was low. That’s the thing about being a caregiver, you can be in extreme denial or hope. When there is no progress, you try to convince yourself that there may be. So you have to find a sweet spot to deal with that reality.”

He worries if his father is cognitively aware but can’t communicate, imagining the terror of suffering in the silence, the world not knowing you are awake. According to Anthony, his father was a man who loved to chat, and is now nothing like his former self.

Between caring for a heartbroken mother, a cancer-stricken mother-in-law, and a vegetative father, it’s unfathomable that anyone would still think of getting into politics. And I haven’t even gotten to his daughter’s and wife’s medical issues.

But perhaps the outcome has also been that in dealing with such adversities, he has cultivated certain altruistic sensitivities that steer his political compass. The personal is political, as they say.

He describes his outlook back then: “I just didn’t see a general problem with society and I had no interest in politics. It was when I looked up the history of the presidential elections that something struck me. This is the highest level of office and yet there is no competition. How can there not be other qualified people around? With the exception of Ong Teng Cheong, it doesn’t make sense that they all be walkovers.”

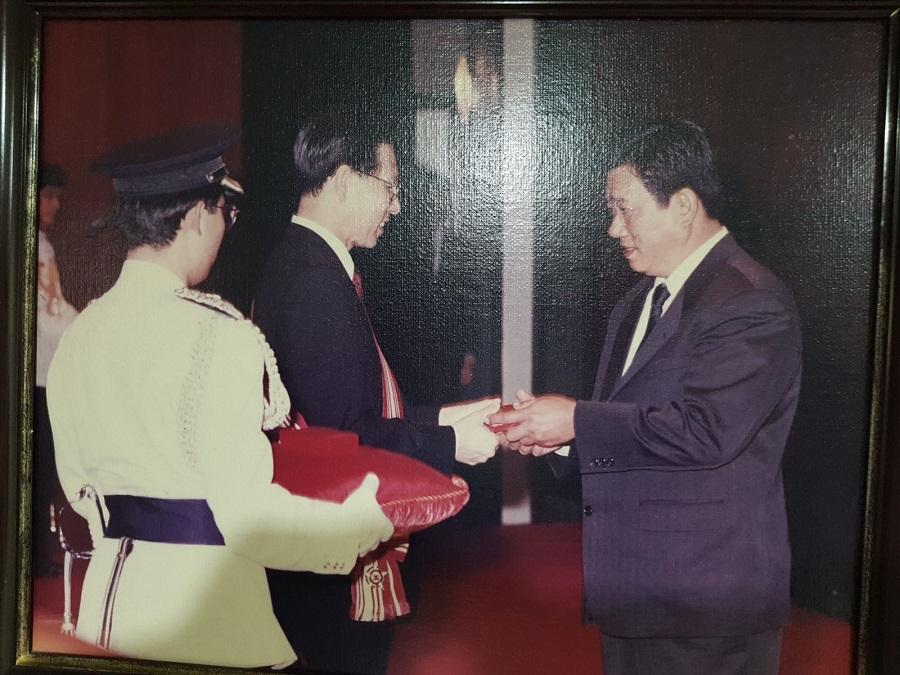

The 6 months spent campaigning for Dr Tan would turn out to be an eye-opening experience. There’s also a reason why Anthony attaches significance to ex-President Ong Teng Chong’s legacy: his father received a Public Service Medal award from him in 1993.

For all his criticism of the current system, Anthony prefers a less confrontational position to the ruling government. Instead, he opines repeatedly on the importance of a political culture, insisting that “the nature of the beast has to change. Singapore, to me, is like a blank canvas. What do you want to paint on the canvas? We must never say things can’t change. If we get the right people and leaders, we can explore & offer different possibilities to people. For example can we create a retirement system that matches dollar for dollar in retirement funds? We may be a small country but we also can play a big role globally.”

Anticipating questions of his view of the PAP, he clarifies that what he feels is not hate but disappointment. He acknowledges the positive aspects of PAP governance, but wants to address several things which can be improved. Among them: the design of the economy, the political system, education system, unemployment, and cost of living. These have been some of the fundamental interests for his father and him.

He concedes the government isn’t wrong in defending that Singapore faces the same uncertainties as other countries. But he is discontented with how they don’t facilitate an open democratic environment, and are just as confrontational and divisive as they make out their critics to be.

Stressing on the exigency of cultural change, he suggests that there should be a collaborative spirit from the ruling party, “If I am the ruling party, I will reach out to the other parties, including NGOs, VWOs and ask how can we do this together? Every party is entitled to their own ideology, but the ends are the same, we want things to be better, just that the means are different. We shouldn’t be discordant and work together.”

As someone who has interacted with the health system so frequently and painfully, his criticism of the system is surprisingly tepid and moderate. He praises the system for responding to human needs first, and setting aside billing later.

His contention lies instead with the lack of mental health care, which he feels should be provided every step of the way for both patient and caregiver. A recent instance of this was his daughter’s case of Kawasaki Disease, a rare illness which causes inflammation in blood vessels throughout the body.

Because she exhibited atypical symptoms, it was hard to diagnose. He came away disappointed with the lack of support from the hospital in helping them understand her condition and how life threatening it can be. They were only told that the cost of treatment would be high as she required transfusions of IVIG (an antibody extracted from plasma) and that each bottle was worth about $1000.

She needed 11 bottles.

He tells me, “Nobody supported us so we felt quite helpless and had to step up for ourselves.” As is to be expected from Anthony’s charitable nature, he became a volunteer and gave talks at some pre-schools to increase awareness.

He doesn’t deny that more can be done for the costs of medical treatment. Due to the lengthy nature of severe illnesses, post-hospitalization measures can be stepped up & costs better supported. He even experimented with a business venture to sell cheaper medical equipment and supplies, which unfortunately didn’t pan out.

Like a utilitarian philosopher, he acknowledged that while the rich can deal with the costs better, “during the actual process, the pain is no different. We shouldn’t judge from the outside and instead find how to improve things.”

We debate on his political ideas. I am not sold on the idea that the rich suffer on the same level as the poor. As someone concerned for the plight of the average person, I cannot fathom that the level of pain and hardship will be the same for them. If you can afford tonnes of carrots as a means to heal your cancer, you are better than the family subsisting on $3 cai fan meals while trying to pay for chemotherapy as well.

We also discussed his notion that all political parties aim for “the same ends even if the means are different”. It is platitudinous to think that everybody pursues the same goals in society. Some are perfectly fine with the poor suffering on their own with minimal support from the state, while others campaign for enhanced welfare benefits even if it comes at the expense of higher taxes. There will be no politics of conflict if his adage was true.

He opines that “I’m not into the politics of plain hindsight in terms of criticisms. It generates too much hatred and vitriol online especially. It’s easy to say anything can and should be better indefinitely. It is more important to learn instead from it. We need to know what went on behind the scenes that led to decisions being made. It is sometimes hard to do that without the data or information. That is where transparency and accountability matters.”

Hearing his rationalisations, it seems to me that Anthony can perhaps be too affable for his own good. To learn important lessons from the past requires criticism that can sometimes be harsh. Harshness does not equate to hate; we can criticise a politician for not heeding the advice of NGOs or considering other policy solutions without being hateful.

Even in issues of transparency and accountability, it is precisely when a gross oversight has been exposed, that demands for more transparency gets stepped up, which the Covid-19 outbreak at the foreign dormitories or the Parti Liyani case have demonstrated. Particularly for the latter, the PSP has called for an independent review to scrutinise the lapses as indicative of “underlying systemic faults”.

That being said, perhaps this never-look-back attitude is what keeps the man going. Currently, he is on insulin and some other medications. Though his daughter is still undergoing treatment for her current infection and requires life-long monitoring for Kawasaki disease, she tries to participate in all activities like a regular kid.

Meanwhile, his wife suffers from visual snow syndrome—a condition which causes a person to see numerous flickering tiny dots in their visual field. Describing it as similar to the black and white TV static seen on old CRTVs, there is no established cure, and all they can count on is medicine to reduce symptoms.

He has been able to manage the medical expenses thanks to his wife and daughter having insurance for hospital care. However, it’s still financially stressful as their claims are inadequate for managing their life-long conditions. Given his own medical history, he is currently uninsured. As we speak, he is expecting a bill from his pancreatitis hospitalisation, which he estimates to be over $10,000. He may need to secure a private loan if he is unable to claim through Medisave or MediShield Life.

His relationship with the PSP has also transformed. As the youngest member in the CEC, he had conceptualised the PSP, creating the party name, slogan, and its constitution’s ideals, among other things. Due to his daughter’s condition, he stepped down in January 2020, and is now the Head of Conduct and Discipline.

He jokingly suggests that he deserves a Guinness World record for having the worst luck in the world. A friend adds plaintively, “Will your luck run out one of these days?”.

Anthony is not religious. But like others who have undergone near-death encounters, there is a profound transformative effect on their views of life. Anthony has converted these hardships into teachable moments about grit, “There are many times that I felt things could have gotten worse. What I can say is there’s no rock bottom. Life can come along with a shovel and dig even deeper and push you harder. But you get up and grit, and go on.”

Everything that has happened has taught him the importance of being there for people.

“To what end and eventuality doesn’t matter. By helping others, I found purpose but lost myself in the process. Once you forget yourself, philosophically speaking, it helps to get through things easier because you will always put others before yourself and that you can always still help others even if you are in a difficult situation yourself.”

In some psychology and spiritual circles, it is said that the key to a good life is to lose yourself in a social cause. But paradoxically, the more you lose yourself in it, the better you may feel about yourself due to the goodwill generated in helping others.

And it is through all this that perhaps you show the world who you really are.