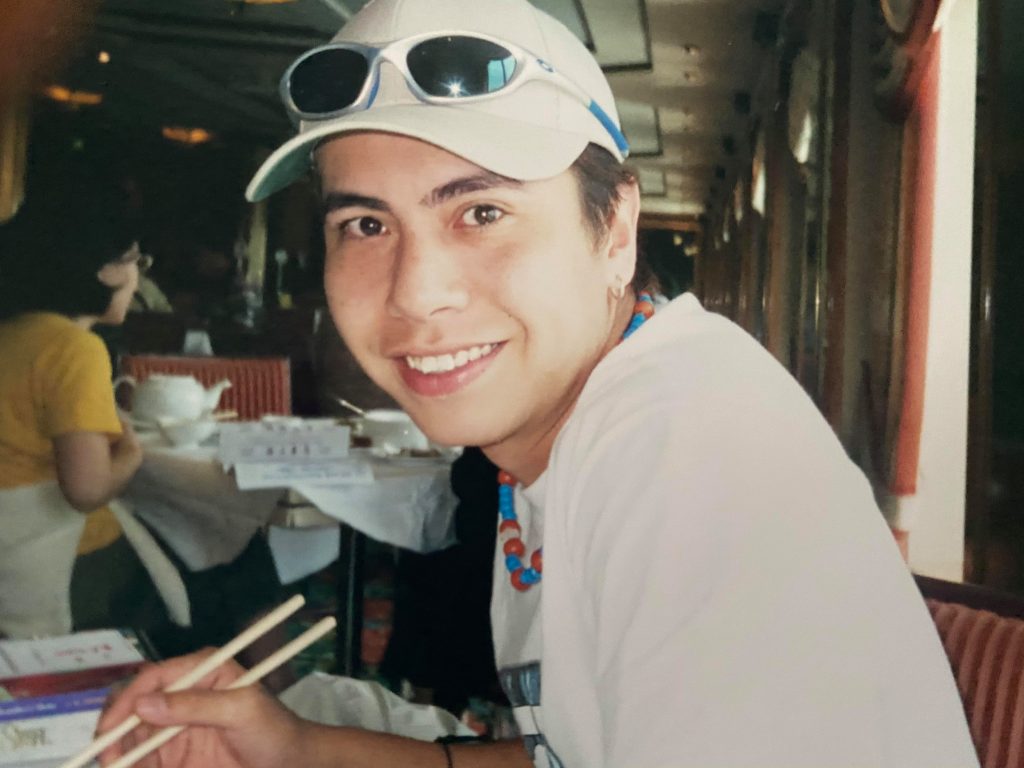

We kicked off the series with Wendy, the Singaporean woman who manages Hollywood’s biggest stars, followed by Jasmine, the Singaporean woman who was friends with Pablo Escobar’s drug dealer. Now, we bring you Wesley Godden, a Singaporean man who owns a 200-acre sheep farm in Canada. This story is told from his perspective.

Being about 16-years-old, moving was exciting. Canada was already at the forefront of human rights, and their laws prohibit against discrimination based on ethnicity or sexual orientation. This allowed me to come out and be who I am.

There I got a double major in political science and communications, and a post-grad certificate in Fundraising and Volunteer Management. After graduation, I worked for a number of NGOs in Toronto.

I always thought I would have moved back to Singapore after university. It’s home, and for many Singaporeans going abroad, it is a matter of gaining new experience for a few years. But I realised it wasn’t going to be so easy for me to come back when I met my partner in school in 2000. Singapore wouldn’t be able to provide me with the same equality and freedoms they provide hetero-normative couples and families, so I decided to stay on in Canada.

Sexual orientation is protected under the Canadian charter of rights and freedoms, so Canadians are very accepting of gay people. Here, I’ve never felt discriminated against. Jobs are protected and marriage is equal for everyone. In Singapore however, my friends feel like second-class citizens. You can get fired if you are gay. You can’t marry or adopt, you can’t purchase a HDB with your loved one.

I have many gay friends in Singapore. Although they are able to hold a job and hide their sexuality, they don’t feel free to truly be themselves in many ways.

Since I have been living out of the city and closer to nature, I feel more connected to the seasonal changes that happen every year. These allow me to engage with the environment around me in different ways, and from activities to clothing, there is a cycle that stops anything from becoming stagnant.

For example, I’m preparing for the winter now, so there is still a lot of outdoor work to do. I wake up, feed the animals, then do various chores like clear bushes, cut trees. I also have various projects running at the moment, like building a chicken coop.

This lifestyle excites me and makes me happy. And while most people think my love for the wilderness grew once I moved to Canada, that isn’t true. Surprisingly, it was my upbringing in Singapore.

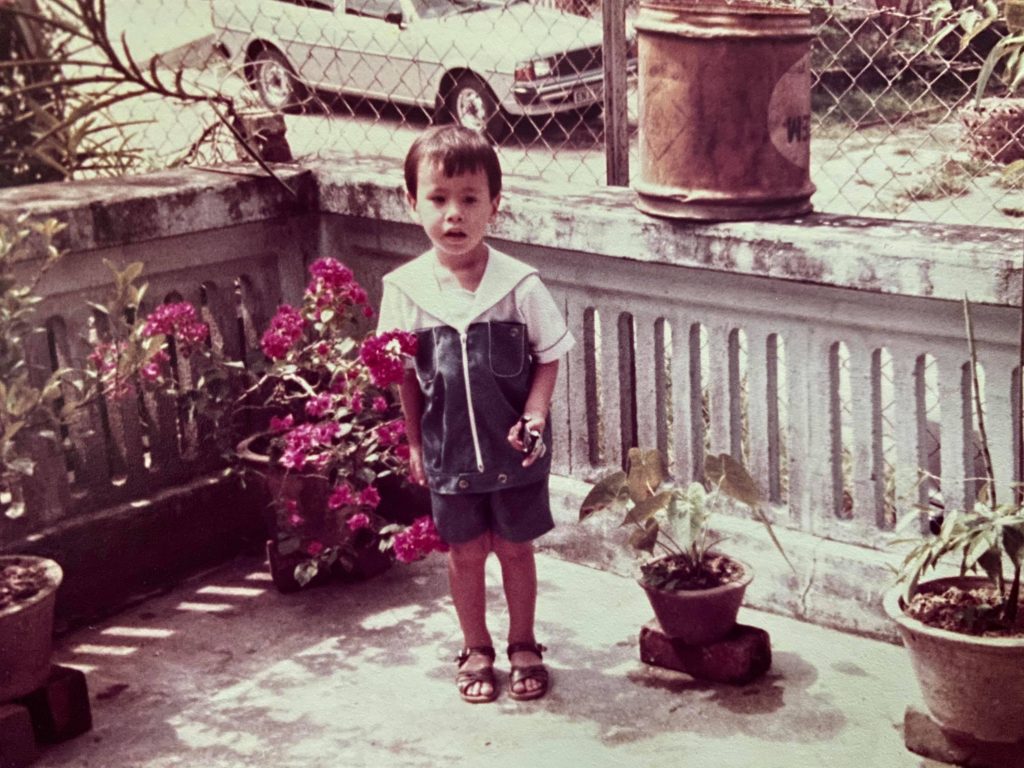

Growing up, my grandmother lived in a kampong near Sembawang. She had chickens and fruit trees—rambutan, custard, apple, mangoes and a few others. There was a community of people living together, and it was a very natural way of life. A lot of the food we ate came from the land around us, and I was exposed to different farm animals that are harder to come by now.

The kampong has now been demolished, but my interest in crops, plants, and animals never left me.

There were countless restaurants and shops everywhere you turn, which I’m not used to. Living on a farm here I can go two weeks without buying anything. But the moment I step out in Singapore, I need to pay for something—it’s like the country is a giant shopping mall. You are always going through commercialised places.

For decades the environment and the economy were seen as separate entities that oppose each other. Now, people are realising that the environment is our home. If you tear down your home to make money, sooner or later your home will be distorted and you will end up homeless.

The idea that nature can and should be commercialised defeats the idea that we are all part of nature and taking care of nature is taking care of ourselves. In Singapore we are only now looking at food sustainability and the protection of nature, something that we should have done a long time ago. Almost all the land for farming is taken up, but I hope the country continues to find ways for nature to coexist in society.

That is also why I have built this life for myself, and although simple, it makes me happy. It teaches me everyday that success is not always about how much money you have. Everyone wants something different in life, and that’s okay—there is no single metric for when you have ‘made it.’ All the money couldn’t give me the life I have right now if I lived in Singapore.