“Be careful, he might be damn annoying to you,” a mutual friend tells me.

But even though I’m on my guard from the second we shake hands at Starbucks, he bursts into laughter the instance I ask, “Let’s get to the crux of the matter – why are you doing this?”

Surprisingly, his laughter isn’t sinister in any way.

In that moment, he transforms into that mischievous classmate you once had who would sit at the back of the classroom, often giggling to himself because of his own pranks and frequently inducing others to join in.

“This”, in the above-mentioned question, is Jeremy’s alter ego. When he’s not working as a healthcare professional, he roams the web as an internet troll.

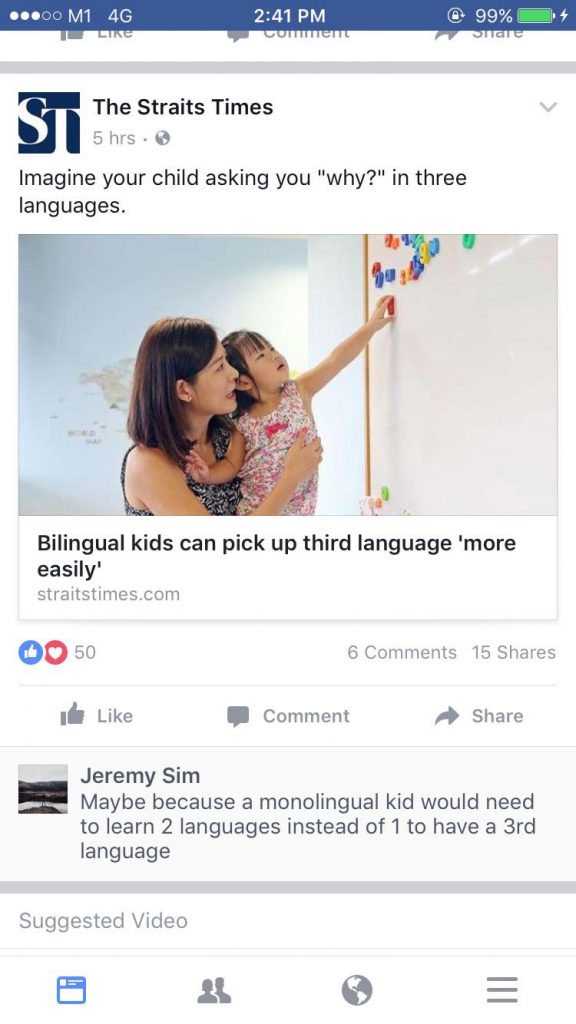

If you follow the articles posted on the Straits Times’s Facebook page, you may have seen in the comments section a witty remark or two by a young man whose display picture shows him in a unicorn suit.

Here’s an example:

A lot of this is in response to readers’ comments, as Jeremy finds “the display of ignorance and stupidity by commenters online atrocious”. Often, comment threads can descend into meaningless virtual quarrels when someone disagrees with an opposing point of view. Singaporeans get triggered way too easily, he thinks, and it’s not necessary.

And so he joins the fray ‒ to lighten things up and hopefully restore some balance to the virtual society.

“The ST Facebook page is the most cancer-causing thing on the face of this Earth. I could live in Fukushima for five years and I would still get a lesser cancer than from reading the section,” says Jeremy.

“I look at the average commenter and wonder, ‘Is the average Singaporean really like that? Holy shit’. I can’t believe it. I just pray to god that each and every one of these people are also trolls. I hope for their own sake. It’s so bad.”

Jeremy doesn’t mince his words. He speaks his mind freely and relishes being sarcastic – perhaps the result of being raised as an only child by open-minded parents who encourage his intrepidness when it comes to voicing opinions.

At the same time, Jeremy doesn’t just resort to quick-firing on his keyboard or hollow and shallow remarks when it comes to trolling the internet. Every joke is painstakingly crafted and quality-assured before he hits “send”. If not, he does not bother posting at all.

He is also selective about when he actually comments. If the comments section on a Facebook post is already bustling with activity, he moves on, even if the news article deserves a dose of sarcasm. The joke only works if people read it; better still if it becomes the top comment and is thus the first thing that readers see.

“There is no point to summoning my brain energy to craft a joke if it gets buried and does not get the visibility it deserves,” he laments.

Still, he says he is not after the attention. The number of Facebook “likes” on his comments don’t matter to him, though deep down he treasures the appreciation shown to his art.

So if you do get his humour, kudos to you. You are the audience that Jeremy is pandering to.

Sometimes, the intention is more venomous, spiralling into outright cyber-bullying orchestrated to hurt.

In contrast, Jeremy’s modus operandi never leans towards personal attacks, and he does not comment on articles about race and religion. He says that it’s not funny any more when it gets too personal.

“Directly flaming someone is never going to achieve anything, like ‘Oh you stupid asshole’ – that doesn’t help anyone. But if you make a joke out of it, or if it’s something that is not a direct personal attack on someone, that’s more constructive.

“You can’t just throw ad hominem attacks. You have to explain to people why they are wrong, not just tell them that they are wrong.”

Instead of watching the world burn with his posts, he wants to open the eyes and minds of Singaporeans to the ludicrousness of the world we live in today.

For example, he could not resist a dig at the recent Reserved Presidential Election.

But instead of voicing his dissent directly on a related news article, Jeremy chose a more tangential approach.

His target? McDonalds’s Nasi Lemak burger.

I suspect this is how George Orwell would have used Facebook.

“It’s a joke! Our political situation is a big fat joke!” exclaims Jeremy, unmistakable exasperation in his voice. “I want people to see for themselves how ridiculous the whole thing is.”

It is the superficiality, and at times “plain stupidity”, of Singaporean netizens that irks this joker, and motivates him to trawl ST’s Facebook page (sometimes Channel NewsAsia’s) for the next opportunity to spread his own brand of enlightenment.

“First, I’m trying to help people not take things too seriously because some things are just obviously stupid. Second, I hope Singaporeans can be more discerning in the things that are happening around us right now,” he says.

It sounds idealistic and even nonsensical as way to justify his online mischief. But this also sets him apart from the typical Internet troll.

Still, he admits he gets a cheap thrill out of provoking the naive.

He can’t remember exactly when he started his trolling exploits, but he recalls creating a separate Facebook profile in his first year at university five years ago.

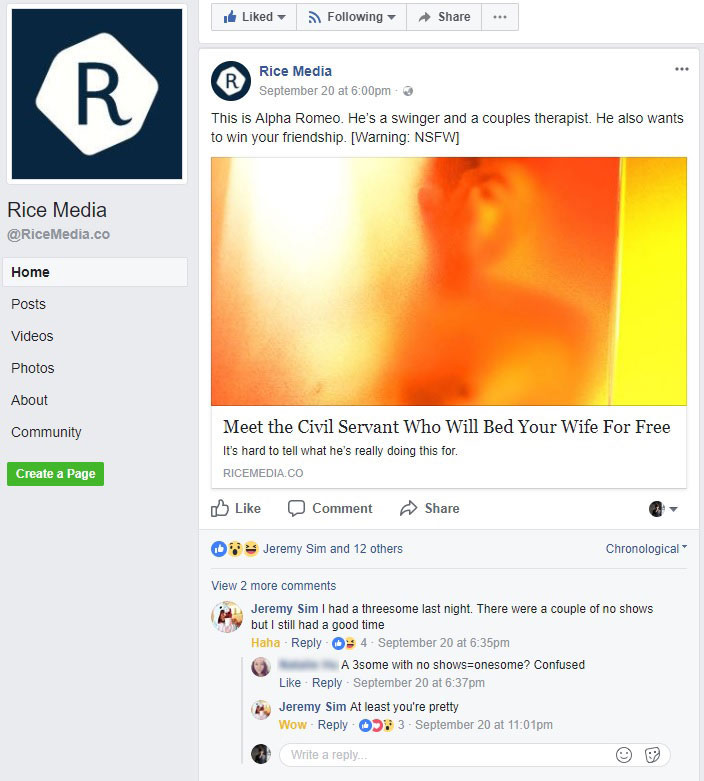

“Johnston Tan” had the personality of an innocent child who says plainly stupid comments that can also sound snarky. His mission: to rile netizens with his blindingly obvious thickness, like this comment:

Jeremy Sim had to, well, unleash Jeremy Sim on the internet.

While Johnston Tan’s naivety is somewhat similar in style to Ken M, the world’s greatest Internet troll who gets under the skin of readers and forum users by passing off clearly made-up stories as fact, Jeremy uses his personal Facebook account. And he has been doing so from the beginning. What you see online is what you get in person. Sharp, silly, and sardonic.

Furthermore, it’s a display of honesty that proves he stands by what he says online.

Trolls thrive under the “online disinhibition effect” – the idea that one can remain anonymous online and so not experience any of the negative social impacts that similar face-to-face encounters elicit.

Hence, publishing one’s true identity is a deadly sin in Trolling 101 as it makes a troll vulnerable to attacks. But Jeremy doesn’t give a shit.

To him, it is precisely this hiding that displays spinelessness.

“I’m absolutely not concerned about using my own profile. Especially the statements that I want to make, politically or otherwise, hiding behind a fake profile is just a sign of weakness. If you ever want to say anything, you show who you are.”

Is he afraid of the repercussions?

“I’m not worried at all. People have the mentality that the government is watching you, and everything you post must be anonymous. I don’t care. If the government is crap, we have to let them know that real people are unhappy.”

He adds, “I believe that everyone has the right to be stupid and say things that are totally not true, and they also should be allowed to do these things without receiving any flak.”

This is true even for Amos Yee, whom he sees as a “silly arrogant dumb kid” who should not have been persecuted the way he was. From the perspective of a troll, there were other ways to deal with his offensive postings.

“By giving him all this attention and responding to him, you’re just giving him what he wants.

“People are just too sensitive nowadays and get easily offended. They should just laugh things off. I believe through and through that humour can heal anything. You can make a joke out of anything by making light of the situation. Everyone can just smile and laugh it off, and we can be so much happier regardless of the situation.”

Yet one thing is for certain – Jeremy proves that my presumptions of how a troll behaves in person are flawed.

I often imagine internet trolls as mean weirdos who hide in their bedrooms, scouring forums with a permanent evil grin on their face. According to a study done by Australian researchers, trolls are typically social recluses – a stereotype also perpetuated by this famous South Park episode.

But in conversation with Jeremy, I find myself engaging with a clever and eloquent man who also pursues creative pursuits in music, photography and filmography with friends. He seems completely normal.

Still, the idea of him toying with the emotions and intellect of the faceless public on Facebook (many of whom could possibly be his patients, home after he took care of them in the day) is bizarrely funny yet fascinating.

George Orwell wrote in his preface to Animal Farm, “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” Jeremy shows us that there is a way to make people listen, and if we want to see progressive change in a society that is so uptight, we certainly need more people like him.

Whether his methods are truly effective, only time will tell.