Photography by Marisse Caine.

This is part two of a series of articles about Singaporean masculinity and how it is changing. In this episode we unpack whether gym bros are the face of toxic masculinity. We speak to fitness enthusiasts about their experience in the gym, exercising with other men, and their personal journeys with body confidence.

Gym regulars should be familiar with that type of gym bro. The one grunting excessively while curling heavy dumbbells, furiously dropping them on the floor upon reaching the end of his capacity. The one who walks around like they own the place, needing everyone to know he is the most jacked in town.

The moment I started this series on Singaporean Masculinity, I knew there was something to unpack about the gym, a place where men sometimes go to assert their dominance or masculinity.

At the same time, the reality is that the vast majority of men in gyms are not that kind of gym bro. They have personal goals, enjoy pushing their bodies, and genuinely want to improve their physical strength. But there is still something about gym environments—the judgmental stares from the ultra fit guys, the cliques, and the hogging of equipment—that can reek of toxic masculinity.

What do the men who live and breathe in these environments really think about it all?

“I started gymming when I was about 20 because I felt the pressure to look good and have big arms,” said 29-year-old fitness trainer Lokies Khan.

Lokies and I discussed how we both hated PE in school, but eventually felt pressured to go to the gym like many other boys our age did. Unfortunately, this is a far too familiar tale for many men and women who start their fitness journeys. And for many, these endeavours do evolve into a love for sports and fitness in their own right, which is healthy. But at adolescent ages, this is often not the case.

The Irony Of The Female Gaze

Take Brent, for example. The 25-year-old NTU student said that he started gymming because he was an overweight child. “I always thought men had to be muscular,” he explained.

On top of wanting to get fit, Brent started becoming an avid gym-goer to attract girls. “I only ended up attracting other guys,” he laughed. Ironically, guys are more amused by muscles than most girls are.

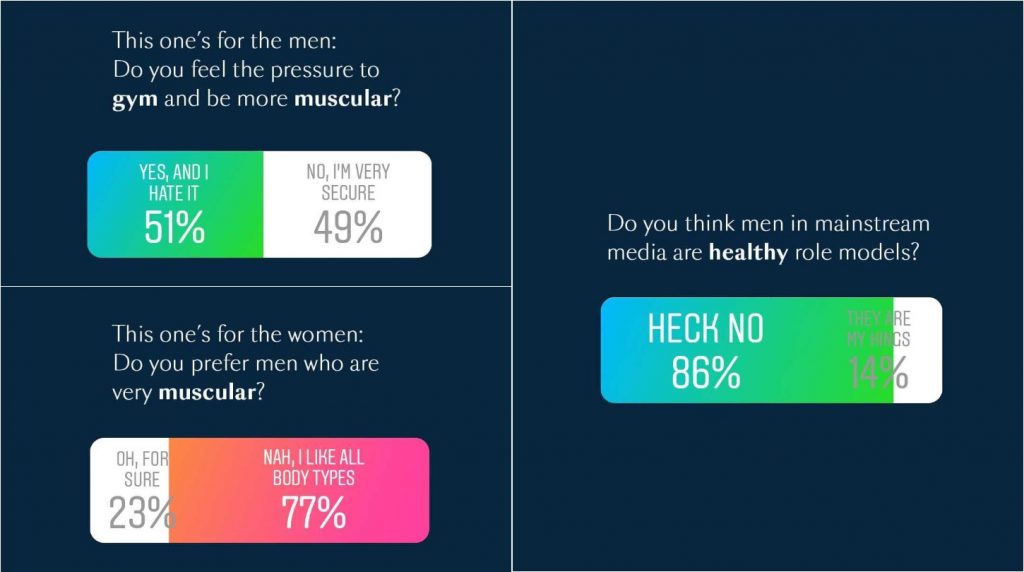

In a poll we ran on RICE’s Instagram, more than 50% of the men who responded said they felt the pressure to be muscular. Only 23% of our female respondents said that they would prefer to date a muscular guy.

A TikTok I saw encapsulated this dichotomy perfectly. In the video, the TikTok user Cassandra said that most straight women she knows find celebrities like Conan Gray or BTS members attractive, while the men she knows perceive them as feminine.

“Men assume this is what women want,” she says, plastering a photo of Chris Hemsworth (who is extremely muscular as Thor) behind her. “But again, this is the male gaze, not the female gaze,” she continued.

“While the male gaze is heavily rooted in physical appearance, the female gaze tends to centre around how a person’s character makes you feel emotionally.”

Cassandra’s explanation encapsulates how the male gaze has instilled in them an idea that physical appearance trumps everything else. But digging deeper, where does this gaze come from?

Unhealthy Representation

Partly, it’s from the men we look up to as a society. Surprisingly, the vast majority (86% of our respondents) voted that the men portrayed in mainstream media are unhealthy role models for young boys. The men I interviewed said the same.

Brent mentioned how he grew up watching The Terminator and joked about all boys growing up wanting the dream “Arnold body.” Similarly, 32-year-old trainer and sports science lecturer Sufian Yusof said that seeing muscular men on the covers of magazines like Men’s Health while growing up a sports enthusiast skewed his understanding of what being fit is supposed to look like.

“Porn definitely influenced me too,” Lokies offered candidly. “It was always big muscular men that were being featured and glorified.”

He shared about the added pressures that come from being in the gay community too. Fit, muscular and straight-acting men are often the preferred type in the community. It is a regular occurrence to find men plastering phrases like ‘masc4masc’ (which basically means a muscular man only wants another muscular man) on dating apps like Grindr.

But gay or straight, social media has amplified the unhealthy representation of bodies for everyone. Fitness influencers and Instagram models are inescapable on newsstands, television, and social media. And while it’s not necessarily bad or harmful to consume fitness content, it’s the body standards younger audiences may internalise that can be toxic.

There is a flip side to social media too, of course, like the body positivity movement. Yet, our obsession with fit bodies still seems to be “rooted deep inside,” Lokies said. “Even with the awareness, it doesn’t disappear.”

When It’s Never Enough

No matter the intention with which one starts their fitness journey, there is no escaping the positive reinforcement from others—which is usually a good thing. For example, Lokies told me that when he started working out, he started receiving extra attention from people around him.

“I rode on it and I enjoyed it,” he recalled. “My self-confidence changed because I grew up hating sports, so the fact that me, of all people, pulled a 180 degree was unexpected.”

While compliments help keep us motivated, they can sometimes keep you chasing an endless goal. All the guys I spoke to—be it gym-goers or those who work in the fitness industry—said they often feel like they need to get stronger and bigger with no endgame in sight.

“Sometimes when I am on some guys’ Instagrams, I wonder how nice it would be to look that good,” Lokies shared.

“If you’re not happy without abs, don’t expect to be happy with abs.”

I stared back in disbelief. How can this man, who has the epitome of the Instafit body, not think it’s enough?

“Maybe the guys I see on Instagram also feel the same. This spiral is not talked about enough,” he continued.

“I’m trying to not attach myself to the image that ‘I am fitness’. It is what gives me purpose, but it shouldn’t be my identity. I don’t know how all the kids are coping now with the overload from social media. If it was me, I’d be pretty fucked up.”

Similarly, it took Sufian many years to break out of this mindset and gain a more nuanced understanding of personal fitness journeys.

“When I was younger, I was influenced by what I thought men should look like,” he said. “Eventually, in my late twenties, I started questioning whether I was conforming, or setting my own rules.”

After studying psychology and researching mental health, Sufian decided to live by a personal metric that fitness is what your body needs at a current point in time.

Like one of his mentors told him when he was training: “If you’re not happy without abs, don’t expect to be happy with abs.”

The Connection Between Toxic Masculinity and Gym Environments

In our conversation, Sufian questioned whether it’s the way “men bottle everything up” that is somehow related to why some men overexert their physical presence.

“There’s a stereotype Asian guys play into,” he said. “I grew up in a traditional Singaporean household where parents don’t express love to anyone. My dad shows strength in character, not by expressing himself. Seeing men bottle everything up was considered normal, and I saw that in my dad.”

In his experience, Sufian has observed how this culture of strong but silent manhood is intertwined with gym bro culture. At the gym, everything is expressed from a physical standpoint, and rarely from within. So if you were raised to be strong and not show emotion, the gym environment would likely make you feel relatively comfortable.

This has a domino effect on a variety of issues. For example, the fact that men tend to be less introspective means they are less likely to point out problematic issues within the fitness community. Or within themselves.

If a woman eats very little, people are very quick to question whether she has an eating disorder. But when was the last time you heard someone question a man for having an eating disorder because he eats eight times a day to grow bigger?

“When you start seeing food as your enemy, or as something you need to be so calculative about, then it can be toxic,” Brent explained.

If someone eats too much or too little to the point they feel sick, or feel like they can’t engage in social activities with their friends, it’s an eating disorder. “Call a spade a spade,” Sufian added.

Yet men don’t realise their relationship with food is toxic, because addressing an eating disorder would probably open a Pandora’s box of insecurities (and other mental health issues) they are not willing to explore.

So what is healthy masculinity?

“What is the opposite of masculine?” Sufian asked. “Being feminine.”

“But what is it like to be feminine? We have a predisposed idea that being feminine equals being weak or vulnerable. But being feminine actually just means understanding your insecurities and showing emotion.”

Nothing and no one is 100% binary. Where one pushes themselves to either extreme of the spectrum, it can lead to unhealthy decisions, spanning from having a bad relationship with food, the bottling up of emotions, or even the abuse of substances like steroids.

Gymming to look hyper-masculine doesn’t necessarily mean you are pushing yourself to an unhealthy extreme, but the journey to get there and the environments you are in can be. For this reason, Lokies said he often tries to counter ultra-masculine environments by showing his fun, feminine side.

When he used to work at annual CrossFit competitions—where dozens of ‘manly men’ convene—he would have a little fun by throwing on a crop top, booty shorts and a wig on. “That’s a part of me I never let myself feel pressured to hide just because of the environment I’m in.”

For other guys, having a healthy relationship with their masculinity doesn’t necessarily have to come in a visual expression of the opposite. It can also mean understanding that everyone is different and has different needs.

Currently, ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ are seen as polar opposites, with a set of defining characteristics for both. But as we continue to deconstruct our conventional understanding of gendered behaviour, perhaps we should be looking to both deepen and expand these definitions of, and see them as less binary, contrasting, and mutually exclusive. At the end of the day, both sides encompass characteristics that we all share, albeit in different amounts. And all of that is completely okay.

What are your thoughts on masculinity? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.

And if you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.