Sitting in on an a cappella rehearsal with Leslie and his friends, there comes a moment when I forget I’m in an HDB flat.

Leslie Tay is 38 this year, and the past few years in his operatic career has been a mix of performing, teaching, auditioning and soul-searching. Just earlier this month, he starred in Operacolypse Now!!, an opera in three parts that saw him spending his last hour at a bar before an asteroid hit earth—not quite what we’d expect from opera.

They’re singing Andy Beck’s A Capella Overtures, and as their voices gain momentum, I begin to anticipate a clash of cymbals at the end. But this doesn’t happen. There aren’t any musical instruments in the room besides an electric piano they’ve been using to tune up.

What I do experience is a deeper understanding of the power of the human voice. I don’t mean this in terms of breadth or loudness, but in terms of emotion. As they run through melodic phrases, Leslie asks Marianne, one of the ladies present at the rehearsal, if she can try to sound more hiao.

In Hokkien, this word translates to ‘vain’. More contemporary uses have distorted it to also mean ‘flirtatious’ or, in coarser situations, ‘horny’. Such sentimental nuance is much harder to achieve with a musical instrument, than with a voice. When they’re done running through the verse, she asks Leslie, “Hiao enough or not?”

Nodding, he replies, “Yes, very good!”

When asked whether it’s true that opera tends to boast diva personalities, he addresses the question by zooming in on what the voice means to those who use it to make a living.

“The voice is such a unique instrument that sometimes singers feel like they’re a special gift from God to the world,” he says, “The thing is, it’s not like if there’s something wrong with my instrument I can just buy a new one. We’re dealing with an instrument we cannot see. Any illness could prevent us from doing our jobs.”

What he says is an understatement of the challenges that he has faced to get to where he is today. When he was growing up, people took music lessons for things like the piano and the violin at Cristofori or Yamaha. He didn’t know he could take voice lessons until he was in his early 20s. There was no School of the Arts (SOTA) either, and when a student asked him why he didn’t just go to the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory, his answer was simple: “It didn’t exist back then.”

Opera, as most of us know it, continues to be dominated by Western and European personalities because of how it was written. It wasn’t written for Asian physiques, which limits how voices sound. Wagner, for example, which requires huge voices, has been said to be impossible for any Asian to sing.

“the best musicians can all communicate how music reflects life”

Having fallen in love with the sound of his conductress’s classical voice when he joined River Valley High School’s choir at 13, he began listening to more and more opera. Like most students of opera, his ambitions began to take shape in a very specific way. There were dreams of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York and the Royal Opera House in London’s Covent Garden. There were dreams of performance contracts, recital albums, and international travel.

“But you go to grad school and sort of realise that damn, everyone else is pretty damn good and much better than I am! And then you go, damn, there are only that many opera companies and there are only that many opera positions available.”

Following this, an encounter with visa issues saw him returning to Singapore from the United States 2 years ago, leaving behind 7 years of work, school, and auditions. Since then, he’s learned to define success differently. He realised that he felt unsuccessful only because of his own narrow definition of what success could be—the international career. But since then, Leslie has started teaching and performing across other genres of singing as well.

“I will always be a student of music,” he says, “Teaching has also made me a better singer. Because the best musicians can all communicate how music reflects life, all this has helped me to come a little closer to that.”

Like Leslie, Evelyn Ang, who is 29 this year, says, “A large bulk of our income does come from teaching others how to sing.” At the same time, she calls opera “Family.” She describes it as the thing that that moulded her into the artist and person that she is today. She believes that it’s the embodiment of human expression.

Yet as one watches her perform Alicia de Silva’s In Our Last, a superb recital combining speech, singing, and artfully dissonant piano and violin, it’s surprising to learn that she nearly dropped out of the industry upon graduating from Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA).

Nearly all her peers in NAFA had made it to further their music studies in the States after graduation, but not her. As she talks about how she began to doubt her own ability, she echoes a lot of what Leslie has said as well: “I’m my biggest hurdle. How far I can go depends on how much I trust myself and my instrument. There’s a fine balance between letting go and freeing up the voice and maintaining control over it. Tip the weight slightly to one end and the whole equilibrium crashes. There’s a lot of mind-play involved in the mastery of singing.”

But a return to basics turned all of this around. With strict vocal training with Malaysian Soprano Joyce Khoo, a full year of coaching helped her regain her confidence and re-ignite her passion. These days, she freelances as a voice teacher at two international schools. She also recently started an arts collective called The Singapore Pocket Opera Theatre (SPOT), which endeavours to make opera more accessible while heightening the level of art appreciation in the region. Just last September, it staged a major recital, SPOT’s Pocket Opera Gala, at the Arts House

For Singapore at least, a lot has been done to keep opera relevant to a contemporary audience. The staging of Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman back in October saw a collaboration with theatre directors Glen Goei and Chong Tze Chien, along with the use of Chinese opera and shadow puppetry, as opposed to 18th century costumes and wigs.

All of these were attempts to make the production relatable. Across the globe, one can now buy tickets to watch opera in a cinema where its screened live in HD. Unlike what many of us tend to think, opera, in spite of its old-fashioned, melodramatic stories of love, revenge, and betrayal, is definitely evolving to respond to modern contexts.

At the same time, Wang Tingting, a Chinese soprano now based in Singapore who boasts a mind-boggling resumé, admits that the association opera has with the rich and the formality of “black tie events” persists. Tingting still sings professionally, but she does it alongside a host of other professional pursuits.

“When it comes to private gigs, we are just like the decoration,” she says with a chuckle, “We are there like how people are dressed in their tuxedoes. I could sing out of tune or sing my French or German wrongly and no one would know.”

She admits that with corporate gigs, it’s often just about the money because no one is really paying attention. It’s a novelty, and no one is there to watch you. She agrees with Leslie that opera is often roped in to make an event appear more posh or artsy. Because opera is sung in European languages, it can lend a perceived air of culture or sophistication. But it’s all just an illusion. The accompanying traditions of dress codes and concert etiquette help to bolster this.

If she sounds a little bit jaded with opera, it’s because she is. While she gigs from time to time, her musical explorations now involve a new collaboration with fusion musician Tze Toh. Likewise, Leslie and Evelyn both continue to sing pop and jazz as well, all while pursuing new projects in performance and theatre.

Compared to other forms, opera can be like the extreme sport of singing

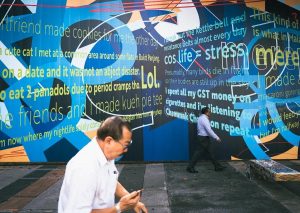

Speaking to these opera singers, it’s almost baffling where the gap in perceptions stands. A poet friend of mine said the other day that it’s almost though if it wasn’t placed in front of our eyes, then we’d just think that it didn’t exist. It’s such a Singaporean thing to do! Similarly with opera, it’s too easy to be cynical about it’s inaccessibility or it’s antiquated ways. Ironically, many who think this have never been for a contemporary opera recital.

While Tingting, Evelyn and Leslie all come from somewhat different generations and experiences in opera, they all agree that the classical form will never die. For them, it continues to be one of the most beautiful expressions of music. As Evelyn also says, “Opera will forever be relevant to society as it is a reflection of society and humanity. Cultures and social norms may change, but human nature will never change.”

But this isn’t to say that there aren’t any approaching shifts in the industry.

Where singers would once attempt to poison each other to get a leg up over one another, opera schools are now progressing beyond its hyper-competitive past to teach students to be better colleagues.

“After all, you never know when anyone would be in a position to give you a job,” Leslie points out.

For these singers, opera goes beyond work. It’s the air that they breathe and the reason they wake up every morning to do what they do. In turn, this passion spills over into other areas of their lives, whether it’s teaching, learning, or finding new ways to succeed and be better.

What we often don’t see is the training that goes into making an opera singer. Compared to other forms, opera can be like the extreme sport of singing for the simple reason that opera singers traditionally sing without microphones. This in itself, the sheer depth, volume, and projection of the voice, continues to be the beauty that these singers pursue in their work.

And with the current generation of opera singers more willing than ever to try new things, entertain, and have fun, we have plenty to look forward to as Singapore’s arts scene continues to blossom.