All images by Edwin Chaw, unless otherwise specified.

This is the second piece in a series on failure—the f-word that terrifies many Singaporeans.

The moment before sunset, he recalls the physical lashings he received from his domestic helper when he was eight. These beatings, which frequently occurred during golden hour, would result in a constellation of bruises on his torso that remained hidden by his clothes.

There are several possible reasons why his domestic helper took her anger out on him. First, the stress of being away from her family took a toll on her after six months. Second, some of his family members “weren’t exactly kind in their treatment of her”; she suffered “a lot of verbal and emotional abuse”. Third, he was the youngest and most vulnerable member of the family, and hence easiest to ‘target’.

Mostly, however, Edwin reasons that her resentment stemmed from a singular event: he had foiled her attempt to leap off his kitchen ledge one night.

“After that, she’d threaten, ‘If you don’t do this thing, I will kill myself and it’ll be your fault.’ As an eight-year-old, you believe and internalise that. Because you’re eight!” he explains.

“If I’d told someone, she might have gotten fired, which might mean attention would be drawn to how she was being treated. Then someone in my family would come under dire consequences. And what if the beatings get worse? So, for a very long time, I just buried it away.”

19 years later, sitting across from me on two separate occasions, 27-year-old Edwin is ready to surface old demons for this article that will be attached to his name for life. From now on, every time someone googles “Edwin Chaw”, they will know he was an eight-year-old who stopped his domestic helper from killing herself and thus became scarred for life.

More significantly, doing this might overshadow the other article he’s tied to: last year, he was profiled by the Straits Times for flunking Hwa Chong’s Integrated Programme (IP) and finding success through an unconventional education path.

Whenever I wonder aloud about whether he really needs to paint a bigger picture of the factors leading up to his departure from the IP, he repeatedly states that he has nothing more to lose. He is already acutely familiar with this sense of permanence; all it takes is a touch of childhood trauma to leave an irreversible imprint on its victims, its ripple effect razing every aspect of life.

Rather, this is, first of all, a cautionary tale about sweeping aside or compartmentalising childhood trauma in its immediate aftermath, forgoing the proper navigation of the elaborate cartography of pain that follows.

When you’re forced to grow up overnight—in this case, by becoming an eight-year-old adult—it is akin to building a house without laying the foundation. Everything might look fine, but pick at a brick and the entire structure falls apart.

More than anything, Edwin’s story is about the dangers of being blind to the myriad trajectories that can coalesce in a single, pivotal life event, because no one truly knows the extent of what anyone is struggling with.

After the widely circulated ST feature on his life shed light on the IP’s intense obsession with grades, his school’s lack of empathy towards his inability to cope, and his education journey after IP, his ‘failure’ was perceived to be the direct result of the IP’s insane benchmarks and his academic inability to meet them.

But, even though the ST article mentions that “he was faced with problems at home and started suffering bouts of anxiety”, in reality, his academic unravelling was far less straightforward.

During a family altercation one night, the police were called to his home by his neighbours. Halfway through the confrontation, one of his loved ones (whose identity I’ve omitted to protect the individual) left the house with a stool. The next thing Edwin knew, he was face to face with this person standing on the 10th-floor railing.

“That moment was very difficult for me to comprehend. I remember dunking water over my head after that and asking myself why it all felt so weirdly, eerily familiar. I experienced this massive dissociative episode,” he says.

Of course, he figured out why he was experiencing ‘deja vu’. But, like he did when he was eight, Edwin compartmentalised the experience in the time immediately after the incident. He went to school the next day to “resume some sense of normalcy”.

As he wandered around the school in a daze that day, his history teacher sent his best friend to look for him. Not to pull him back to class, nor to chide him about the consequences of skipping class, but to simply sit with him and pass on the message that he could return to class whenever he was ready.

But, as he should’ve known, life would never be normal again. He would never be “ready”.

Emotionally, Edwin shut down. To get over the trauma of watching a loved one attempt suicide, he tried rationalising the incident by convincing himself it wasn’t that bad—no one had died and there had been no ‘real’ consequences.

When he did try alluding to the suicide attempt with a counsellor, he was repeatedly told that every family had its problems, and that he had to be “resilient” and “find a way to power through”. It didn’t help, he adds, that the ‘trend’ back then was not to air your dirty laundry, and to sweep these issues under a rug lest they bring shame to the family.

“When I heard the message of resilience at the same time that I couldn’t fully comprehend what’s going on, that made me clench up a lot more for a lot longer. There was a huge disconnect in my head,” he shares.

Academically, Edwin’s grades tanked. He had internalised that self-preservation meant focusing on studies and nothing else, but trauma is a sneaky little bitch, intricately woven into the tapestry of one’s psyche. Every academic ‘failure’ that played out after that night would be interconnected.

For starters, his focus was shot to hell. In one specific instance, he recalls reading one paragraph of literature four to five times without anything sinking in. By the time he hit Secondary Four, he was running on “maybe five hours of sleep a night”. Nightmares were regular, and he frequently had trouble staying asleep.

Eventually, when he was 17 (his first year of JC), everything came to a head.

Still, it wasn’t enough to prevent his third encounter with suicide.

This time, it was his brother who tried to kill himself. After a public fight between with his mother, his brother entered one of his blind rages. He spent the next four hours trying to walk into traffic, while Edwin simultaneously swung between being engulfed by abject shock and overcoming the paralysis of said shock in order to muster enough strength to pull his brother back from the brink of death.

In the end, his brother walked himself to exhaustion. Edwin was simply able to hold out longer.

At the same time that he had to deal with this new layer of trauma, he was transitioning into JC. In secondary school, he always had at least one teacher every year who was willing and able to empathise with his situation at home, and hence afforded him concessions whenever he needed. In JC, there was no one to ‘save’ him.

Relying on himself proved futile. During his end of year math exam in J1, he left the exam hall to visit the toilet about five times, all to puke from the sheer stress and panic. His senses were dull, his vision blurry, his hearing muffled, and he experienced perpetual panic attacks that only got worse by the day.

By the time he approached his block tests during his first year, he was seriously considering dropping out of school entirely.

“I was cautioned by my parents, friends, and teachers about a prevailing view in society that my credentials would matter and all these little slip-ups would be taken into account. But I just didn’t buy into the narrative that my performance at 18 would dictate the rest of my working life,” he explains.

Again, the narrative of perseverance was parroted at Edwin. Since he couldn’t medically certify that he was ‘sick’, it became a case of overcoming his ‘hurdles’ through “mental strength and resilience”. But, as anyone who’s struggled with mental health knows, this ‘solution’ is akin to telling someone to cheer up and expecting it to instantly cure everything.

When it grew obvious he was dealing with something greater than mere academic pressure, the abstract future wasn’t enough to keep him around.

In the end, he dropped out of the IP believing that “these symptoms would go away”.

They did not.

Even though Edwin had left the IP, his panic attacks, nightmares, and struggles with sleep persisted. The following April, Edwin enrolled in Singapore Polytechnic (SP), only to quit four months later in August. Even though SP tried to get him to take a semester’s break instead, he was “too panic-filled” to make a ‘rational’ decision.

“It’s very hard to describe what a panic attack is like to people who’ve never gone through a panic attack. Everything breaks down. Your ability to think rationally doesn’t exist in panic attacks. You’re in a constant state of ominous dread and fear about an unknown and unseen danger that you can’t even comprehend. It’s a complete loss of control, and the despair it brings is insane. It’s not something you can think yourself out of,” he shares.

For six months after leaving SP, Edwin stayed home, just trying to survive. Not wanting to burden his friends, he eventually resorted to maladaptive and unhealthy coping mechanisms. Specifically, he tried to “drink [his] way out of it”. This led to his fourth (and final—hopefully) brush with suicide.

This time, it was his own attempt.

Explaining his “natural progression” to suicide with the clarity of hindsight, he admits he’s lucky that he didn’t bother to do his research. He simply assumed if he “took enough of something”, it would work.

That night was particularly quiet, and his thoughts were particularly loud. He swallowed some pills and knocked out. When he woke up the next morning, he was mildly amused that his suicide attempt hadn’t worked, as though it was all part of a sick joke that some greater power was playing on him. Unsurprisingly, he did what he’d always done: he disengaged and carried on with the day as per usual.

Ironically, he later found out that what he took wouldn’t have been able to kill him.

All the same, it took finally hitting rock bottom for him to turn his life around. It appeared that trying to die was precisely what kept him alive.

Around the same time, he completed a diploma in counselling with Kaplan. In the private institution, he came full circle with the “determinism in our education system”—the same logic that fuels the pressures of being in the IP. He’s referring to the notion that if you do A (flunk the IP; get a private degree), you will end up at B (a failure in life).

He explains that, at the time, there was a perception that his Kaplan diploma would only grant him access to a Kaplan degree, which wouldn’t be fully accepted by employment agencies. To him, this didn’t seem fair, since his Kaplan classmates were clearly more passionate about the course material than his ex-classmates in JC.

Still, it appeared his “only” path seemed to be a necessary return to the “site of his trauma”: he would need to complete his A Levels as a private candidate if he wanted ‘better’ job prospects in Singapore. Alternatively, he could leave for Melbourne, as many Singaporeans do.

Understandably, not everyone has the privilege to up and leave as Edwin does. But while money can get you out of a toxic environment to improve your mental health, it cannot truly buy you peace of mind.

At the University of Melbourne, where he studied finance and economics, he began his first two years “working [his] ass off in a very unhealthy way”. Driven by the self-inflicted pressure of doing well so he could prove that he wasn’t a ‘failure’, he aimed for the Dean’s List in his first and second year because he believed getting it would ‘cure’ his depression. (FYI: he got it, but it did not cure shit.)

In his third year, Edwin finally sought professional help by checking himself into therapy, where he learnt the symptoms he had been experiencing since that fateful night when he was eight were part of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“After every major episode previously, I couldn’t find any answers to the questions I had. Why me? Why is this happening? Did I do something wrong? How do I fix it? How do I go forward knowing this has happened?” he explains.

“So I chose to detach from my feelings about whatever happened. Then after enough time passes, you just kind of forget. But the truth is, the memory is still there. It simply affects you in ways you just don’t realise.”

At its core, that is the lasting legacy of childhood trauma: it shapes you on every fundamental level. You stop registering the disparity between who you are and who you would’ve liked to be, because you learn to compromise the latter in favour of self-preservation. You don’t force yourself to deal with what you need to because you can’t, don’t want to, or don’t know how to.

Edwin’s past inadvertently influenced his present. But as he eventually learned, it was possible to regain control over the future through correcting mistakes, unlearning old coping mechanisms, and confronting himself.

First, he made the decision to withdraw from a second-year module on probability because it wasn’t worth the distress. To this day, he remains proud that his university transcript reflects the word, “WITHDRAWN”, under the module title.

Second, he actively allowed himself to “almost coast”, by ‘dialling back’ from being a Dean’s List recipient to being comfortable scoring in the 60s range. While the old Edwin, who used to be caught up in our society’s limited definition of failure, would have baulked at this sacrilegious act, the new Edwin no longer thought being ‘average’ was necessarily bad, especially if it helped his mental health.

“I told myself I would stop engaging with my education for the purpose of getting an A, nor for the purpose of getting a job in the future. I would engage if I was able to, and if I enjoyed what I was studying. When that happened, it was really cool. The grades just came naturally, and I just wanted to keep learning more,” he shares.

Along the same vein, he began to redefine failure as “tunnel vision”. Instead of treating failure as a “moral insufficiency”, every instance of failure became a chance for him to be aware of what he could do better at.

To the average person, Edwin appeared to be turning his life around. He was volunteering as a tutor, and inventing new ways to understand his modules so he could rediscover the joy of learning. He also adopted an enlightened approach to education: when you have the freedom or opportunity to explore things that you love doing outside of school, you’re more likely to be able to apply what you learn in class to real-world situations.

But he wasn’t done with ‘recovery’ just yet.

After his profile in ST was published, Edwin connected with me on LinkedIn to share more. He wanted to talk about the influence of his experiences with suicide in order to normalise the conversation around the still taboo topic.

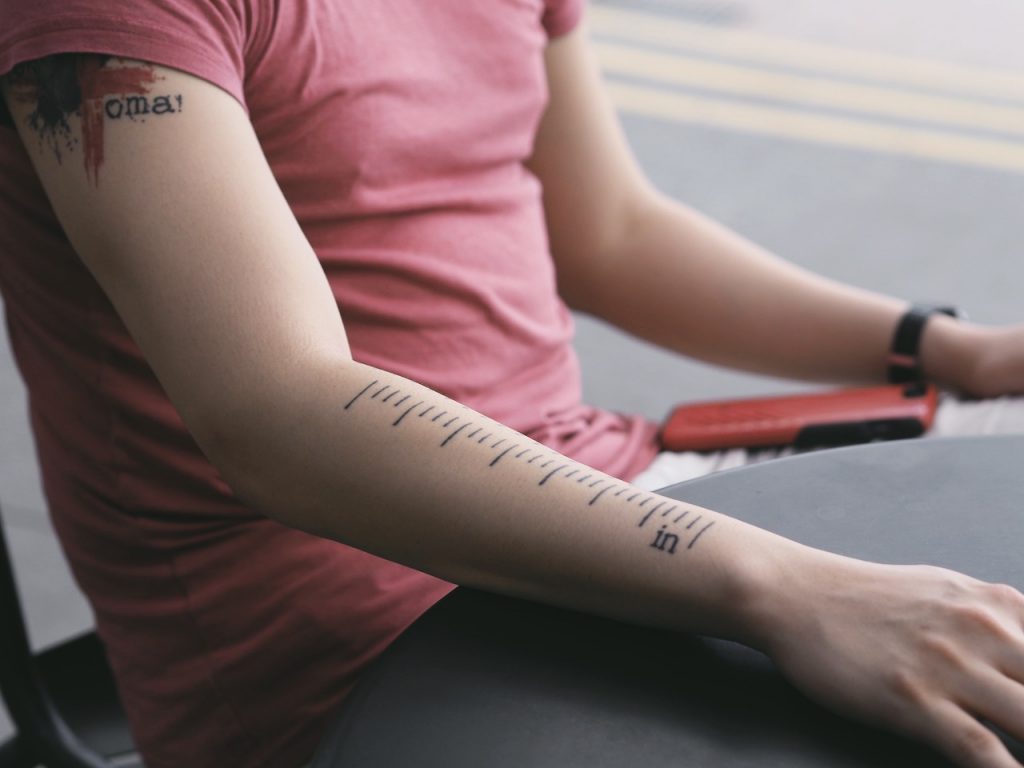

I meet Edwin twice. Yet, it’s only towards the end of our second meeting that I finally understand why he would desire to dredge up his past and connect the dots of his private life via a public platform. His right forearm sports a tattoo of a 20-cm ruler—it has increased his arm’s “utility”, and also reflects his own ethos of “viewing our bodies and minds as tools that we can continuously refine and upgrade”.

Similarly, he believes sharing his story would help others battling similar traumas—and, although he doesn’t say it, I sense that scrupulously going over every detail of his life multiple times helps him let go of the past. In this, he has grown to embody what author Junot Díaz (another victim of childhood trauma, and, unfortunately, an alleged perpetrator of abuse later in life) once wrote: “You can never run away. Not ever. The only way out is in.”

Ironically, despite quitting the IP, he’s also seemingly lived by his alma mater’s guiding principle: 饮水思源 (yin shui si yuan), which loosely translates into having gratitude for what has happened.

Every 24 hours, Edwin Chaw’s world cracks apart during golden hour. But after 19 years, he’s realising a new reality: There is a crack in everything. That is how the light gets in.

For everything else, there’s community@ricemedia.co.