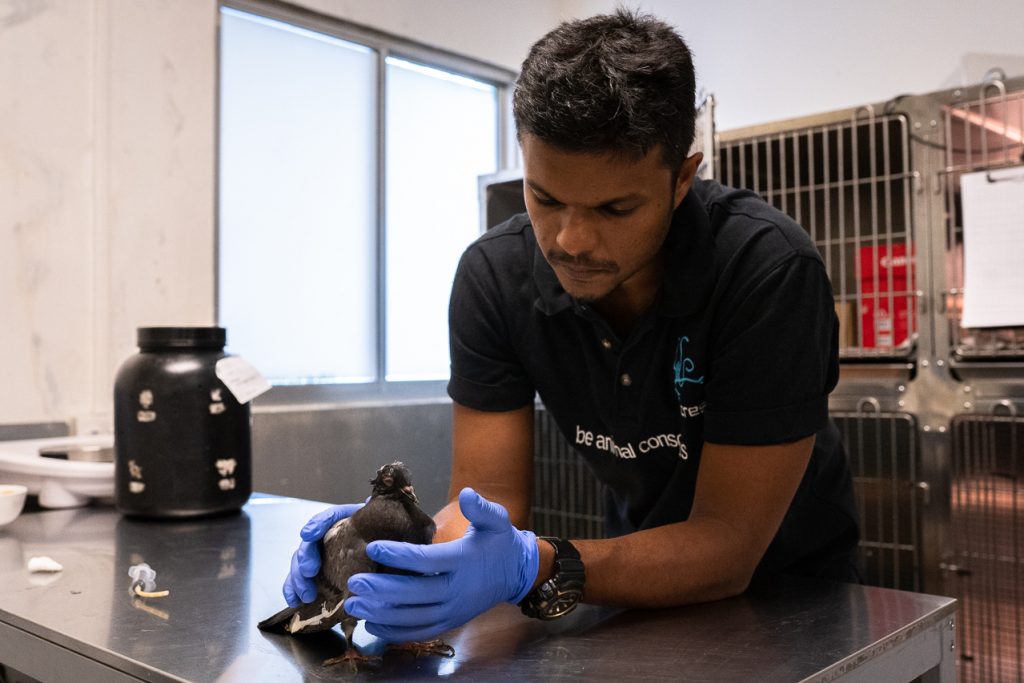

Top image: Dr Venisri and Kalai of ACRES treating an injured crow.

She remembers that it was a civet. She remembers being woken by her colleague at 2 AM to look at it. She remembers that its skull was completely exposed and fractured after being knocked down by a taxi driver. She remembers how every ragged breath it drew sent waves of pain through its shuddering body.

Most of all, she remembers realising there was nothing she could do to help the suffering civet, except end its pain by euthanising it.

“A child would only know being a vet is helping animals, but when I had to perform the procedure on an animal, that’s when it struck me,” Dr Venisri says.

“It’s also ending suffering when necessary.”

But wait. Wildlife? In Singapore?

Before my visit to ACRES, I, too, was amazed: my most intimate brush with ~wild Singapore~ was when a praying mantis somehow flew 10-storeys up and crawled into my bedroom.

Kalai Vanan Balakrishnan, the Deputy Chief Executive of ACRES, is unsurprised by my surprised face. Citing the recent incident in which Jane Goodall, famed primatologist, was scandalised when she learnt that Singaporeans think wild animals belong either to the zoo or the bird park, Kalai sighs, “A lot of people don’t know Singapore has lots of wildlife.”

In fact, despite our heavy urbanisation, Singapore boasts a rich biodiversity.

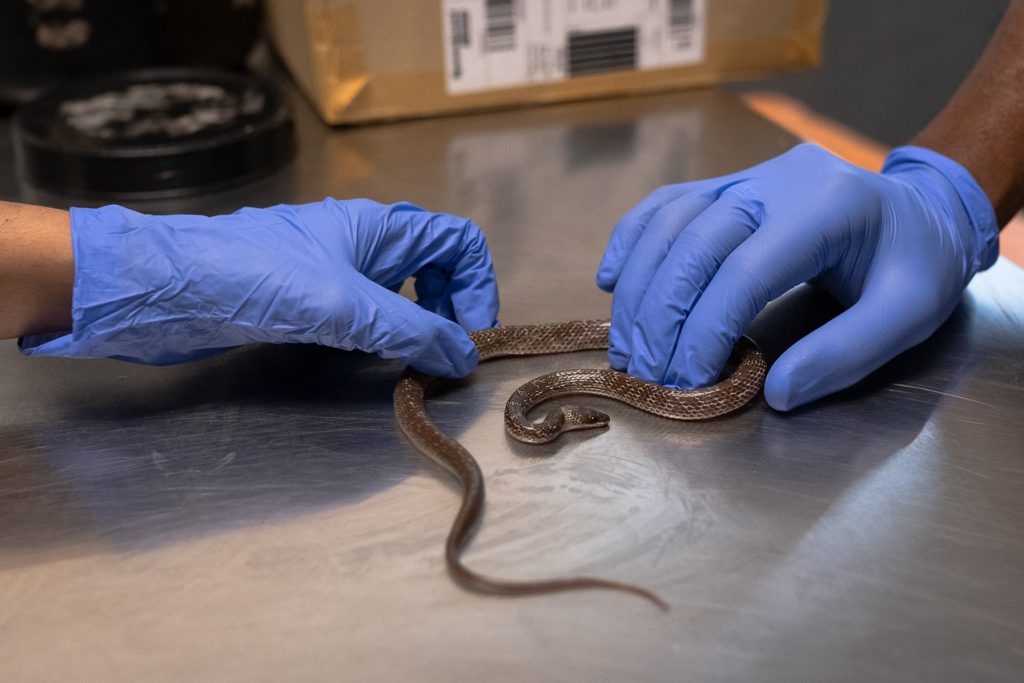

“We have pangolins, which are the most endangered and most heavily trafficked animal in the world. We are home to over 60 species of snakes, and among the 60, we have the world’s longest snake and the world’s biggest venomous snake. We have the python and the king cobra. We have thousands of migratory birds. We have crocodiles, dolphins …” Kalai enumerates.

Wilderness in Singapore, then, doesn’t just mean that stretch of grass and water in Bishan Park that plays hosts to a family of otters. There are patches of uninhabited land where thousands of wild animals call home—though these idyllic spaces are rapidly dwindling due to planned development, such as LTA’s decision to build a train route that runs directly across our central catchment area.

The ACRES Wildlife Rescue Centre is as rustic as any place in Singapore can get. It is domed by a sky unbroken by buildings, surrounded by an expanse of greenery where the grass sways at waist-level, and enveloped by a constant symphony of birdsong.

20 minutes by foot from the nearest bus stop and a 40-minute journey from the nearest mall, it’s also the last place in which any Singaporean would want to work, let alone live.

But far from the comforts of a typical veterinarian practice and nestled within Singapore’s wilderness, it’s the very place that Dr Venisri wants to be.

“I’ve always wanted to work with wildlife,” Dr Venisri explains. “Dogs and cats have owners: someone who loves them and can provide them with food and shelter. Whereas wild animals don’t have owners. They don’t belong to anyone, so they don’t have anyone to look after them.”

She quickly qualifies her statement: wild animals don’t need humans to look after them. On the contrary, their injuries are mostly inflicted by humans.

Our culpability ranges from the straightforward, like accidentally stepping on a common wolf snake and breaking its spine (seeing a snake wriggle desperately, but helplessly, is one of the many heart-wrenching scenes I witnessed during my visit), to the more long-term devastation of urbanisation and deforestation. For the latter, just think of the increasing number of animals—most of them critically endangered, like the Sunda pangolin, the leopard cat, and the sambar deer—being run over drivers because their habitat is being encroached by the construction of 5 new wildlife parks in Mandai.

Pause for dramatic irony.

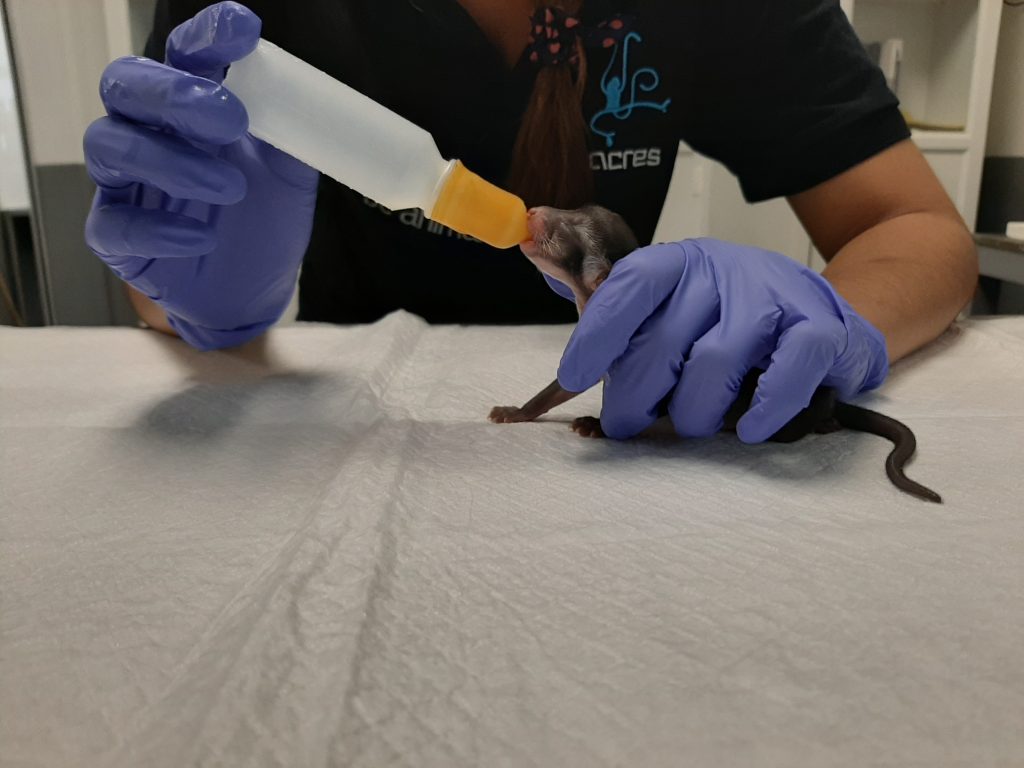

This is where ACRES and Dr Venisri come in. Together with the team at ACRES, Dr Venisri rescues and treats as many of the injured animals as she can.

“Being able to help wild animals, regardless of species … for me, and probably all wildlife vets around the world, it feels like we’re making a huge difference for them.”

Yet many people misunderstand what ACRES does. They ignore the word ‘rescue’ in ACRES’s wildlife rescue centre, and think of it as an abattoir that immediately euthanises any unfortunate animal sent there.

It’s a touchy topic. Kalai visibly bristles when I bring up the topic.

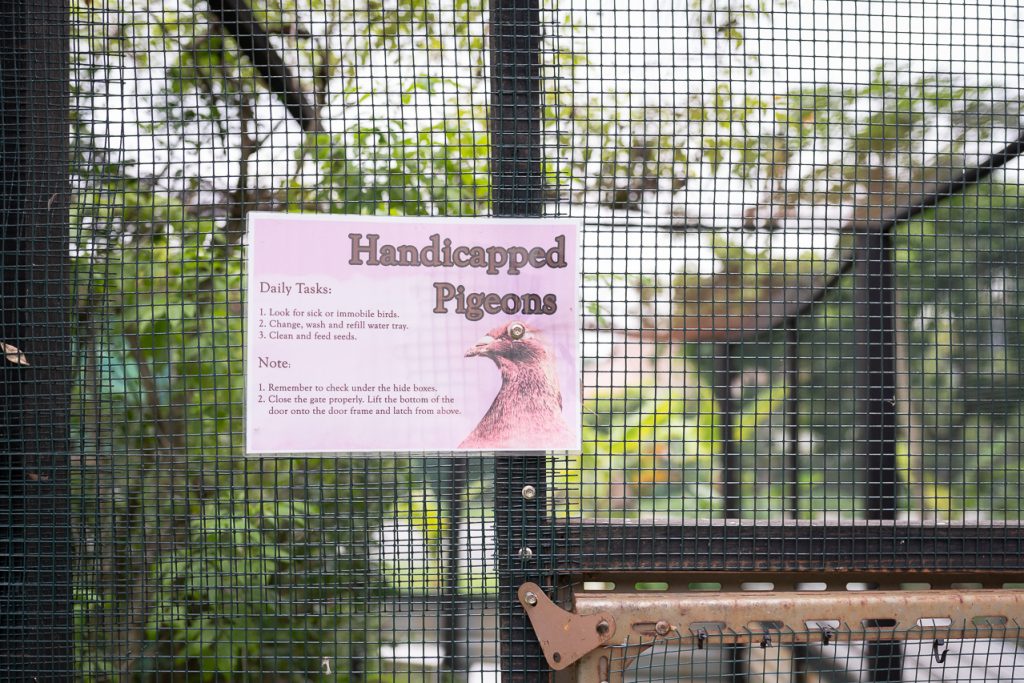

“We have always branded ourselves as a no-kill shelter. People misunderstand that. In some NGOs or organisations, the moment they have no space, they will euthanise the animals. That is something we don’t do. We only euthanise when they are badly injured, extremely sick such that they cannot recover fully, or are unable to be released as a true wild animal,” Kalai stresses.

“People don’t recognise this. They think, ‘Send here straightaway euthanise’. Sometimes we drive all the way to some place like Changi to rescue a pigeon. And the first question they’ll ask me is, ‘You all won’t put it down right?’”

“I won’t come all the way to here just to put down the bird!” Kalai exclaims in exasperation. “No, we are genuine about this. We take euthanasia very seriously. We are very strict about it.”

As Dr Venisri emphasises, “It’s not easy to decide these things. Humanely euthanising an animal is always the last resort. It means there’s really nothing else that can be done anymore. Otherwise we would have tried.”

The following questions are some of their considerations and criteria that determine whether an animal should be euthanised:

How severe is their injury or illness?

For animals with serious physical injuries like shattered skulls or impaled lungs (in the case of mammals), the chances of survival are close to zero. In these cases—like that of the wild pig/civet that was Dr Venisri’s first euthanasia patient— the humane thing to do would be to put the animals out of their suffering as soon as possible.

Unlike physical injuries, which manifest superficially and are visually obvious, certain illnesses tend to lurk beneath the skin. Thus, animals can appear healthy even though they are suffering from a terminal disease that “takes time to eat away” at them, Dr Venisri says. But we cannot let their surface presentation sway our emotions.

Just by looking at an animal, you would not be able to tell that it is suffering from a chronic illness or disease like septicaemia (also known as blood poisoning). Yet, according to Dr Venisri, this secretive disease—so to speak—is one of the most “painful, cruel, harsh, and slow deaths” an animal can have.

“If I know an animal is suffering greatly, I would never …”

Dr Venisri takes a pause to compose herself.

“I would never have it suffer longer.”

Some animals take the rallying cry “Give me liberty, or give me death!” quite literally. Within 24 hours of staying in captivity, they experience huge amounts of stress, go into shock or starvation, and die.

Once confined to a man-made enclosure, adult wild boars, for example, would use their 100-kilogram heft to bash around the space, eventually inflicting so many injuries on itself that it dies—even if it were admitted only because of a mild, treatable fracture.

More delicate and sensitive animals like some wild birds or colugos simply go into shock and stop eating entirely, slowly wasting away and dying of starvation.

Therefore, if ACRES comes across these animals, it has to make the morally heavy choice of keeping them in captivity and subjecting them to additional stress during the treatment period, or euthanising them to prevent further suffering.

At this point, some of you might wonder: if the injury is mild and treatable, shouldn’t the animal be left in the wild for it to recover fully?

But what is medically or surgically treatable and what can be recovered from naturally are two entirely distinct categories. To give the simplest example: prior to the discovery of penicillin, we humans would probably have died of bacterial infection from superficial cuts because our bodies cannot resist large amounts of bacteria naturally.

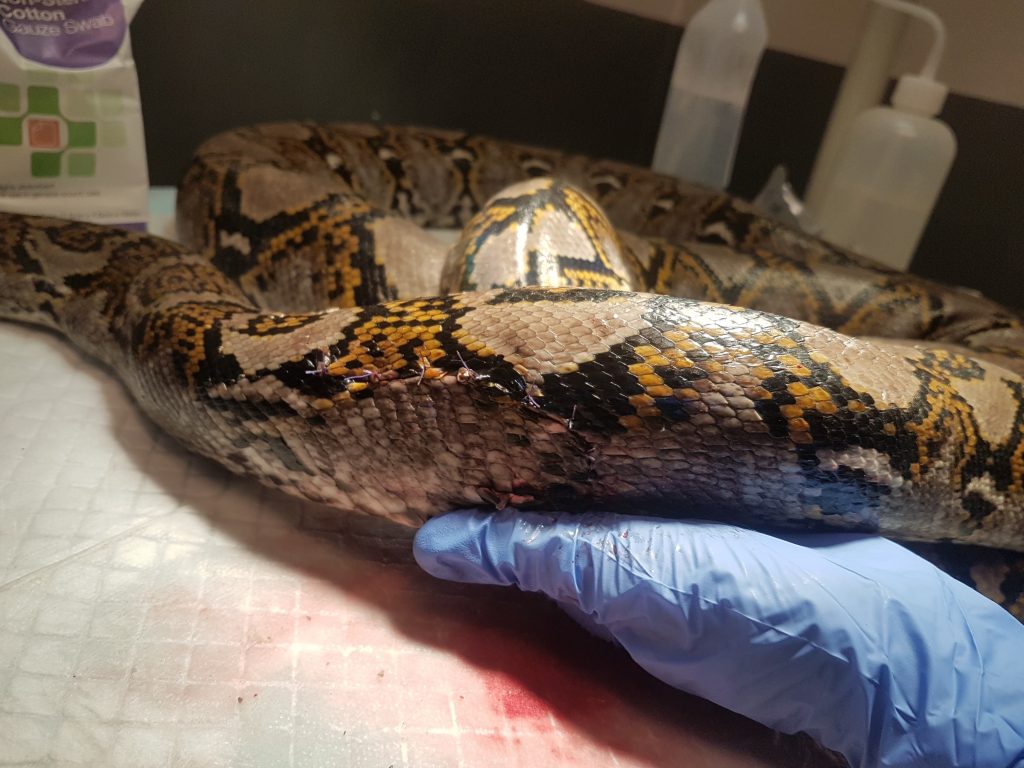

ACRES has saved the life of many injured and ill animals: snakes with skin tears or a broken tail; birds with respiratory disease; monitor lizards with an ugly fish hook piercing through their mouth. These animals have all been treated and released back to the wild after they have recovered.

But there are some cases in which the damage done to the animal is irrevocable.

“We can fix the wing of any bird and then release it after it has been repaired,” Dr Venisri says.

“But will that affect the flight of the animal? Let’s say it is a kingfisher who has to dive into water to get fish. Even if we fix it in a very conventional, conservative manner, if it’s never able to fly and dive into water like a normal kingfisher, what’s the point of releasing a bird that’s going to crash and die outside?”

ACRES is an NGO (non-governmental organisation, usually non-profit, as ACRES is). Despite the important work it does for Singapore’s wildlife, it constantly struggles with a lack of resources and funds.

“We don’t even have an X-ray machine,” Dr Venisri mourns. “We depend on SPCA [which is located about 5 minutes, by car, from ACRES]. It’s difficult because these are wild animals, you have to sedate them. The transport itself will cause a lot of stress.”

ACRES doesn’t have an autoclave machine, either. An autoclave machine uses pressurised hot steam to sterilise equipment. In a medical setting, it is typically used to prepare equipment for surgery (though most hospitals today use single-use instruments, a practice which, in the long run, is more expensive than owning an autoclave machine). Because they don’t have an autoclave machine, Dr Venisri cannot perform sterile surgery—typically more complex procedures—on animals.

“We can only hold small-scale ones,” she says regretfully. “So even if I read up on a certain surgical method [that can help the animal], we can’t do it.”

“All these things play a huge impact on how much we can do. If we had an advanced clinic we can do way more. We can build specific enclosures for specific types of birds. We can surgically fix things that can’t be done now.”

“Knowing that I cannot do [all these things] I feel … it saddens me and it makes me feel like crap. Like I can do so much more [for the animals], given the opportunity. But I cannot.”

Yet this is still not enough for some. For a select group of people, there are no grey areas; no human should be allowed to conduct euthanasia.

“They say we’re not god. We shouldn’t decide the fate of an animal,” Dr Venisri laughs helplessly.

Other people, thinking of themselves as compassionate, offer to adopt an injured animal. As you’ll recall, keeping wild animals in captivity is a terrible idea that can literally cause its death.

Even for wild animals that are able to survive (note that I’m using the word ‘survive’, not ‘thrive’) in captivity, they will inevitably develop health problems eventually.

So they bring it home, thinking they can take care of the liddle floofy things they have already named. They feed the animal at regular intervals, but this prevents it from learning how to find food in the wild. So when the animal grows up and loses it baby-faced charm, people lose interest in it and release it at the nearest forested area, where the animal is going to starve to death. Slowly.

Or people bring the animal back to ACRES when they finally admit they have no idea what they’re doing.

“By the time people bring the animal to us there’s usually a lot of issues. Their nails are overgrown, it comes in with metabolic bone disease, it comes in with hypoglycaemia … Wild animals have very specific needs. People need to understand it’s not the same as looking after domestic animals,” Dr Venisri sighs.

And, yes, sometimes the issues are so severe that euthanasia has to be conducted on the animal. Because some kind soul wanted to save it from ACRES in the first place.

Pause for dramatic irony. Again.

This problem boils down to selfishness, essentially. In Dr Venisri’s words:

“They don’t understand a wild animal is supposed to be wild regardless of what you want. You don’t put your needs before the animals’ needs. Always the animals’ needs first. Not ours.”

Yet the negative perception of ACRES persists.

Part of it is a PR problem, Kalai admits. Dr Venisri says, “of all the animals we actually help, the ones that get the negative feedback from people are the 2 that had be euthanised. [No one pays attention to] the 20 we’re trying to help.”

It’s easy to post nasty Facebook comments on ACRES’s page when you don’t understand what they do. It’s easy to call ACRES’s animal rescue hotline and hurl abuse at their staff and volunteers—a too-frequent occurrence, Kalai reveals—when you mistakenly think they have a cavalier attitude towards euthanising animals.

It’s not easy to help the wildlife in Singapore. It’s not easy to do the job that ACRES does.

Even though with each euthanasia process Dr Venisri is forced to conduct, her technical skills improve and she gets more familiar with the anatomy and physiology of various animals, “the emotional side …” she starts saying.

There is a very long pause. At my feet, Sunshine, one of the dogs that live on the ACRES compound, shifts lazily, stirring a mound of dust.

“It never gets easier. To see an animal that is dying, in pain, bleeding, it never gets easier.”

To donate to ACRES, click here.

Tell us how you think we can live more harmoniously with wildlife in Singapore at community@ricemedia.co