As guests trickle in to take their seats, an instrumental version of “I See The Light” from Disney animated film Tangled plays softly from the overhead speakers. Minutes after the service begins, a white casket with a young girl dressed in an angel’s costume (complete with wings and a wand) rolls out.

This is no ordinary funeral.

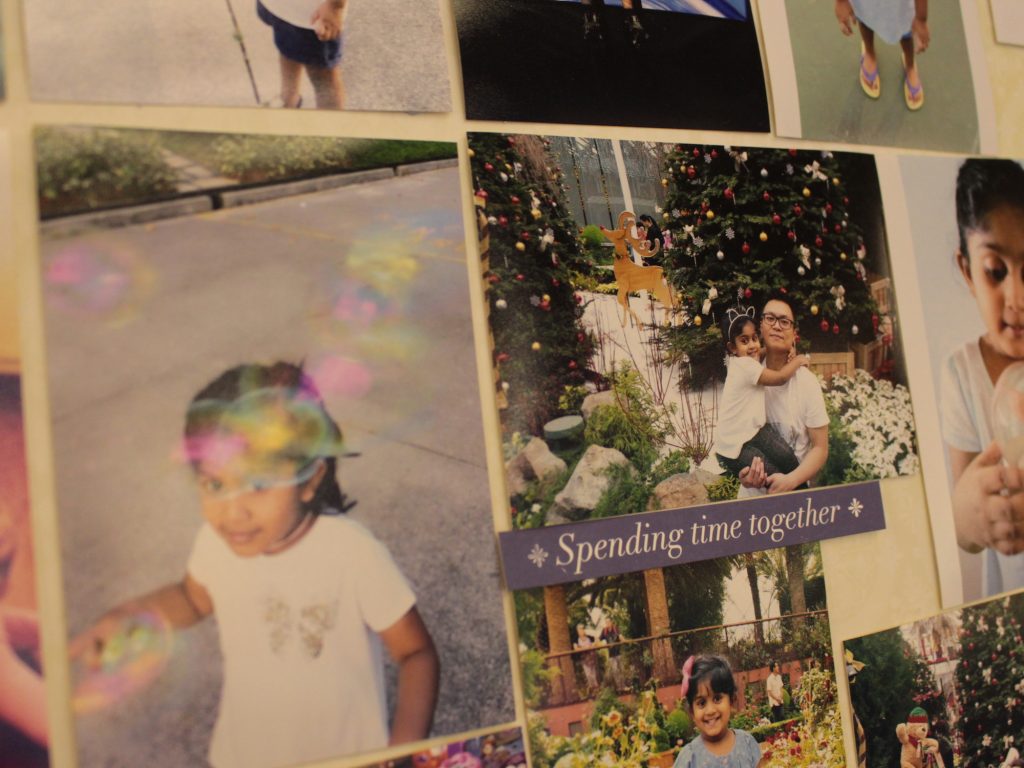

Six-year-old Misha Peh, the daughter of Rynthia Mathew and Peh Wei Hao, was a precocious child who seemed wise beyond her years. Eternally curious about the world, she would “ask questions that normally those from her age group wouldn’t ask”, Rynthia tells me. In fact, she loved to study and was hardly seen playing with toys—an oddity among adolescents.

Wei Hao recalls a time when she displayed the wit of a lawyer, and twisted vague instructions about her candy intake to her advantage.

“You tell her, ‘You can’t have too many sweets. Once a day is fine.’ So she’ll ask me once a day if she sees me,” says the 36-year-old.

“Later, I found out she’d been asking once a day to everyone. She’ll get one from her grandpa, grandma, me and even her helper.”

Clearly, this was no ordinary girl. In fact, so extraordinary was she that she planned her own funeral, calling it a farewell party instead because “funerals are for the dead”.

Wei Hao explains, “She wants people to remember her smiling and not in pain. She wanted it to be more like a celebration of life, like a birthday party.”

Her theme of choice was a combination of princesses and rainbows. Though she was for the most part choosing from a list of options offered by funeral planner The Life Celebrant (TLC), she was no less particular and had an opinion on everything.

“Even that particular detail of the casket sticker … she didn’t like the [original] design. She wanted wings, so I had to go Google [for alternatives] and get approval from my little boss,” Rynthia chuckles.

It goes, “All go to the same place; all come from dust and to dust all return”—which also informed her decision to be cremated instead of buried.

Requesting for a two-day visitation (because that was her favourite number, her mother says) at her funeral home, she opted not to lie in the casket for that period of time. Instead, her body was set on a white pearlescent counter, where visitors covered her with flowers, toys, paper hearts, and cranes.

“We weren’t married yet. When I was pregnant, I wasn’t actually ready to be a mom,” the then-24-year-old Rynthia admitted.

“The first thing that came to mind was abortion.”

But upon hearing her heartbeat and looking at the ultrasound image of her daughter, she couldn’t go through with it. From the moment of her birth, Rynthia knew she was special: “She didn’t cry when I gave birth to her. Instead, she smiled.” And that smile never ceased.

“She’s a child that loves everyone and is kind to everyone. She’ll say hi to everyone, even the helper and to strangers,” says Wei Hao.

Rynthia adds, “She takes half an hour to go to school because she’ll tell everyone, ‘Hi everybody! I’m going to school!’ She’ll tell the neighbours, the security guard and all. When she comes home, she’ll take another half an hour to reach home.”

An exceedingly affectionate girl, she insisted on giving her parents a hug and kiss every night before heading to bed, never satisfied if only one of them could be there to tuck her in.

“Most importantly, she will always tell us that she loves us,” Wei Hao continues.

Four years after her birth, Misha was diagnosed with DIPG. What was once mistaken as asthma turned out to be a side effect of the tumour. An aggressive destroyer, it only took a few days after her diagnosis before she started losing mobility and control over her speech. The deterioration was swift, leaving Misha’s parents struggling to cope in its wake.

“We were in shock. We couldn’t believe that such things were happening to us,” says Wei Hao, who was told she had about eight to 12 months left to live.

“Every single day, we kept asking ourselves when this is going to end.”

“We couldn’t cope without each other,” Wei Hao reveals.

“It was a very painful period for us,” he continues, having to witness his daughter undergo harsh treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy—some of which proved to be too much for the petite girl to handle. Once, a session of physiotherapy left her blacking out midway and waking up to the partial paralysis of her right arm and leg.

The therapy procedures were meant to prolong life, but to the young parents, it only prolonged Misha’s pain. After five months, they stopped treatment.

“We listened to our hearts. She’s already in so much pain. Why not make her happy, instead of forcing her to do all these things? It would be more stressful for her,” Wei Hao reasons.

“I want her to be free.”

Still, Misha needed medication to combat the side effects of her disease. Under steroids, she became obese and wouldn’t look at herself in the mirror because of her size. As her weight increased to more than 30kg, her self-esteem plummeted. There were also times when she went through episodes of constant vomiting. Under the influence of certain medications, coupled with the pain, she would suffer mood swings and act out violently, screaming and pushing her parents away.

“But at the end of the day, she’ll apologise and say, ‘Mommy, I’m sorry I told you to go away. I don’t know why I feel this way. I still love you,’” Rynthia says, “You can never hear that from a child.”

“For us to figure out if she’s in pain, it’s hard to tell because she’ll control herself until it’s really severe. Then, she’ll ask you for medication. She’d rather control herself and see us smile, than to see us cry,” says Rynthia.

“I think Misha was touched since she was a baby and she probably came here for a purpose to bring joy to everyone. She taught us about love and family, how to be happy no matter what the situation may be.”

Before her departure on 18 September, she had a moment with her father.

“She told me to take care of my wife and to love my wife,” says Wei Hao. As for her last words, Rynthia remembers her whispering, “I love you, mommy. I love you, daddy. I love you, Jesus.”

A week after Misha’s funeral, I meet her parents again at a cafe and ask how they’re doing.

“Okay lah … Everything is like numb,” Rynthia confesses, “Everything triggers us about Misha.”

Her husband says, “We can try again. But to us, it is a life gone. It’s not something you can replace.”

Here, Rynthia interjects, “To have a second Misha … there’s no way.”

“There’s no way to move on from this,” Wei Hao finally adds.

“We just have to carry all this pain to our last breath. But at the same time, we feel peace. We know she is at peace.”

Know someone remarkable whose story deserves to be told? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.