It’s 2 AM. Along Pioneer Road, deep in the industrial district of Boon Lay, an Esso petrol station with its bright white lights is the only sign of human life.

The Esso sign board gleams like a lighthouse in a sea of quiet, guiding the rare wayfarers in this part of western Singapore to a place where they can fill up their petrol tanks or stomachs, or empty their bladders, before they continue their journey.

While this place is bustling with heavy vehicles and commercial activity in the day, at night it’s as peaceful as a reservoir park. A lorry or taxi breaks the peace about once every 10 minutes, and even fewer vehicles actually turn in to the petrol station.

For Mr Anwar, this petrol station – a 10-minute drive from Tuas Second Link – is a regular pit-stop during his daily commute from Johor Bahru to Bukit Merah, where he works as a security guard.

“I don’t carry much cash with me whenever I ride my motorcycle from JB because it’s not safe,” the young Malaysian tells me. “So I come here to withdraw money from the ATM before I go to work, it’s very convenient.”

The loud revving of his engine pierces the still air as he exits the station. Seconds later, it’s silent once again.

With so little traffic passing through the station, I wonder how the employees on the night shift – just the two of them – deal with the long hours of little to no human interaction at all.

In the five to six years that she has been working as a station attendant, she has never set foot in any other petrol station in Singapore. Pioneer Road may be on the fringes of Singaporean civilisation, but it is the ideal location for the Malaysian lady as she can easily head home after her shift.

And despite the monotonous nature of working at night in an area that is largely devoid of human presence past dinner time, all Rajes really cares about is getting across the bridge without getting caught in traffic once her nine-hour shift ends at 7 AM.

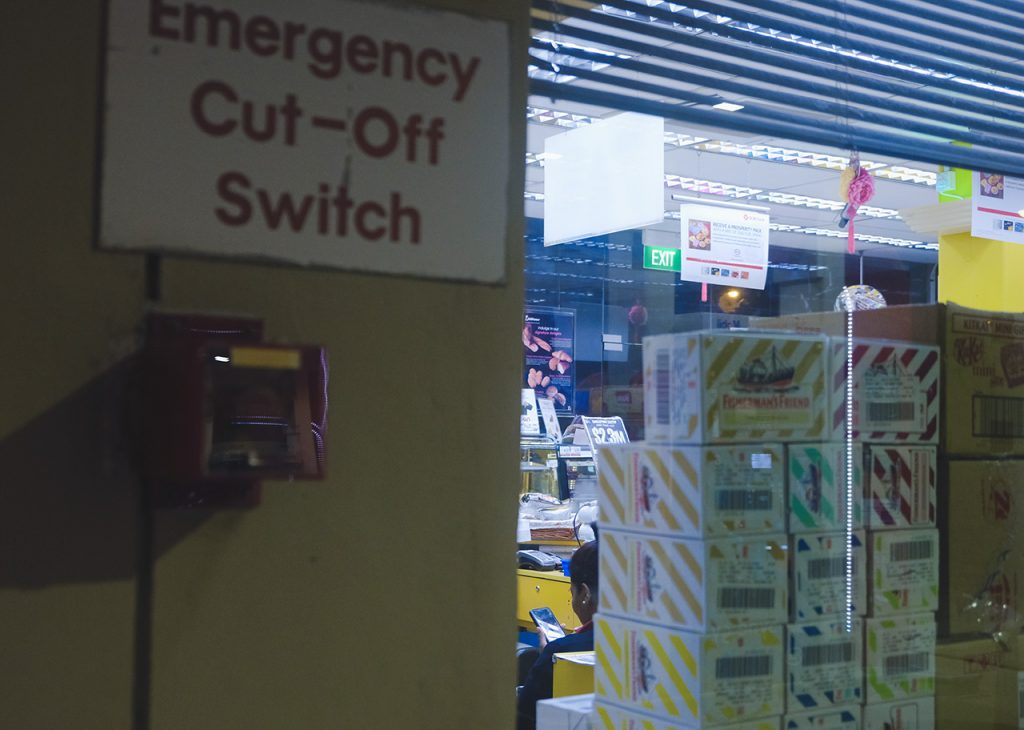

“I like working in a quiet place. And even if there are no customers, I still have things to do like baking puffs and receiving deliveries,” she says. “Sometimes it can get a little bit boring, but I’ve gotten used to it already.”

She adds that in all her years working at the station, this is the first time a customer has struck up a conversation with her.

He tells me that most of the people who drive in are usually policemen from Jurong Island, security officers from the ExxonMobil refinery behind us, or taxi drivers and lorry drivers.

Previously a dispatch rider, Pratap says that working the night shift at the station is a much welcome change of pace. “I felt a lot of pressure in my previous job as I had to make so many deliveries in one day. Here it is much better, things go at an easy pace. I pump petrol when there are customers, and sweep the floors every three hours.”

Like Rajes, Pratap doesn’t seem to mind the lack of human activity during his shift and in fact seems content with the isolation. He spends most of his time sitting on a chair by the kerb outside the station, his eyes glued to his phone unless his colleague needs his help.

In the two and a half hours I’ve spent here, I count less than eight customers. At an uneventful place like this, time slows to a crawl.

Working here is not for everyone, even if it sounds less stressful than a typical office job. For those who subsist on human interaction, spending close to 10 hours, five days a week, in a secluded place like this may feel like being locked up on an island.

In the wee hours of the night, being a petrol station attendant here has got to be the loneliest job in Singapore.