For the Looi family, their embracing of Tibetan Buddhism came about when their father, the late Alvin Looi, once wheelchair-bound, started walking again miraculously.

But let’s start at the beginning.

It is 1996. Alvin is 35 and working as a full-time jockey. Alvin has just been flung out of his horse. He is lying on the racetrack, his spine wrenched out of position.

He consults three doctors from three different hospitals. All conclude he would never walk again.

At that time, Jamie’s aunt was already a practising Tibetan Buddhist. She mentioned a healing lama in India who, after spending 30-years studying in a mountain retreat, became renowned for his healing practice. (“Lama” is the title for “teacher” in Tibetan Buddhism.)

After hearing about the healing lama, Jamie’s mother—the late Karen Lim—wasted no time in bringing her husband to the healing lama’s monastery in Bangalore, India.

Jamie’s voice takes on a reverential tone as she narrates the events at the monastery.

“My mum told me that every morning, for 30 minutes, the healing lama would recite mantras into an ordinary, white PVC pipe directed at my dad’s spine. There was nothing in the pipe. But at the end of the pipe, there would be smoke coming out, smelling like incense. After the healing session, the healing lama would also get monks to conduct prayer sessions for my dad. This went on every day for a week.”

“My dad’s life changed totally after that.”

Upon his return to Singapore, Alvin quit smoking and drinking and became a devout Buddhist. Each morning, he would recite the Chenrezig (known locally as Guanyin) mantra and conduct water bowl offerings—a common Tibetan Buddhism offering that devotees carry out to shed their worldly attachments. Alongside his religious devotions, Alvin exercised daily to strengthen his body.

Three months after the visit, Alvin defied all three doctor’s prognosis. He progressed from wheelchair to crutch, and eventually started to walk again.

Aware that her husband’s convalescence bordered on the miraculous, Karen tried to downplay this aspect. Instead, in recounting the tale to people, Karen highlighted how the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism had completely turned Alvin’s life around for the better.

Such an approach struck a chord with people. Inspired by Alvin’s story, people—family friends at first, then complete strangers who heard about the account through word of mouth—approached the Looi family to find out more about Tibetan Buddhism.

“My ex-colleagues think I’m crazy,” Ivan admits. “They’re earning at least a good amount right now. Recently, one of them even asked me to go back.”

“But I said I can’t. I have to do what makes sense for the people. And I’m actually happy here. ”

The growing number of Tibetan Buddhist devotees in Singapore may come as a surprise to most of us. Influenced by Hollywood films such as Doctor Strange—in which sorcerers clad in red robes conduct rites in temples that are a pale, but unmistakable, mimicry of Tibetan Buddhist ones—we may cultivate the misconception that Tibetan Buddhism is an anachronistic religion characterised by ancient prayer rituals and observances. That is hardly an appealing picture of religion to the modern (and some may say jaded) Singaporean today.

But the rituals that Tibetan Buddhists conduct are not that different from those of any other religion. Catholics conduct baptism, Mass, and confession; Muslims fast during Ramadan and carry out a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lifetime; for Hindus, each day is devoted to a specific deity and different rituals are carried out depending on which day it is. In other words, it would be unfair to single out the frequency or prevalence of rites and rituals in Tibetan Buddhism.

Therefore, to think that Tibetan Buddhism consists only of blindly following elaborate pujas is to miss the forest for the trees.

Case in point: monks in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries are simply university students in red robes. They spend their whole day— from 8 AM to 12 AM—reading religious texts, taking a break only to conduct short pujas, have meals, or carry out their chores. Their diligence is motivated by the monks’ belief that it is in understanding, and living according to, the precepts laid out in scripture that they can extricate themselves from the cycle of suffering.

As with any form of proper study, intense debate—not dogmatic adherence—is emphasised. After every teaching session held by a resident or visiting lama at GSDPL, Ivan holds a discussion session to consolidate viewpoints; the lamas in monasteries also have theological debates with each other over their daily readings, exploring competing interpretations in a manner not so different from university seminars.

Thus, the appeal of Tibetan Buddhism–and, largely, of all forms of Buddhism—lies more in its exploration of universal issues, such as how to live and relate to other living things, rather than in esoteric rituals.

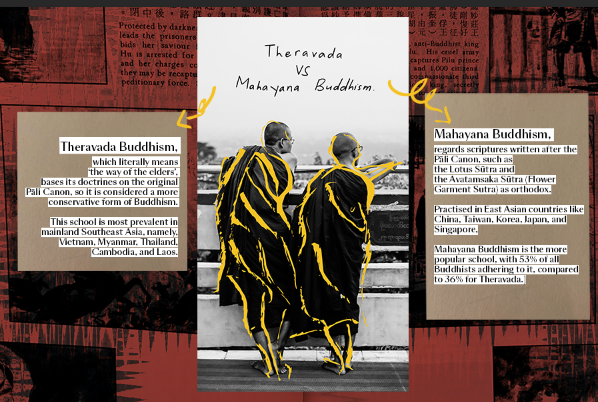

This is what Yulting Rinpoche, a revered lama of Tibetan Buddhism, tells me over Skype. Rinpoche also explains that Tibetan Buddhism’s focus on this notion means that, aside from cultural and terminological differences, “it’s basically the same as … the other schools of Buddhism, whether Theravada or Mahayana”.

Nonetheless, I talk to some regular devotees at GSDPL to find out what motivated them to follow Tibetan Buddhism.

Angela Quek, 25, initially harboured the same misunderstanding of Tibetan Buddhism that many of us have—as a p(r)ay-per-miracle religion, if I may put it a tad indelicately.

She says: “To be honest, back then I had zero interest in Buddhism because my thinking was: ‘Huh? Buddhist need to study one meh? I thought just go pray and get blessing and success in this life can already’.”

It was only after she spontaneously volunteered at a GSDPL-organised event—after being brought there by a friend—that she started to read about and understand Buddhism more.

Today, Angela says that she practises Buddhism daily: “I read dharma and Buddhist-related books and bring what I read into my daily life. For example, I wouldn’t have been particularly kind to people on the MRT before. But now I spare an extra thought for them.”

For Sim Mui Luang, who is in her mid-40s, it was the prominence of lamas, or spiritual mentors, in Tibetan Buddhism that drew her to the religion. “I think I need a fully qualified guide on this journey, a person who only has our best interest in heart,” she tells me.

In short, for some Tibetan Buddhists, it’s a chance encounter that blossomed into a lifelong commitment. For others, it’s a long, sustained inquiry into the different traditions of Buddhism before deciding to focus on Tibetan Buddhism.

“It’s like my family outside home,” Joyce Sun, 29, enthuses. “I always feel very happy to go there, even after a stressful week.”

Wendy Lee, in her late 30s, describes the community at GSDPL as “a closely knit family … with the centre as a 2nd home”.

Joel Ng, who is in his late 40s, is perhaps most fervent of all, typing his reply in capital letters:

[GSDPL] is FAMILY.

“We don’t need people to be Buddhists and we don’t need them to convert. It’s more like how Buddhists concepts such as compassion and loving kindness can add happiness to their lives, even to people of other religions,” Jamie says.

In fact, Ivan sees converting people to Buddhism as anathema to its fundamental principles: “Making everyone a Buddhist will only create unhappiness. It totally contradicts the whole idea of loving kindness, which is the essential idea of Buddhism. As Buddhists, we are not so concerned with what religion you practise.”

Then, Ivan unconsciously slips into the language of his previous job—but in doing so, succinctly sums up the whole ethos of Buddhism: “Our main KPI is whether people are happy”.

“We have a tendency to label things as being Buddhist or not. But Buddhism is not something that you have to follow because it is said that. It is something that is logical and does not rely on superstition.”

“You can say that when someone is feeling compassion to somebody in pain, that person is practising Buddhism, in a way. He may not be a Buddhist, or believe in Buddhism, but he is basically doing what the Buddha has said, which is being compassionate and helping others.”

“If someone does this, it’s because we’re all humans.”

Let us know your thoughts on this article at community@ricemedia.co.