Top image: LittleLoWai

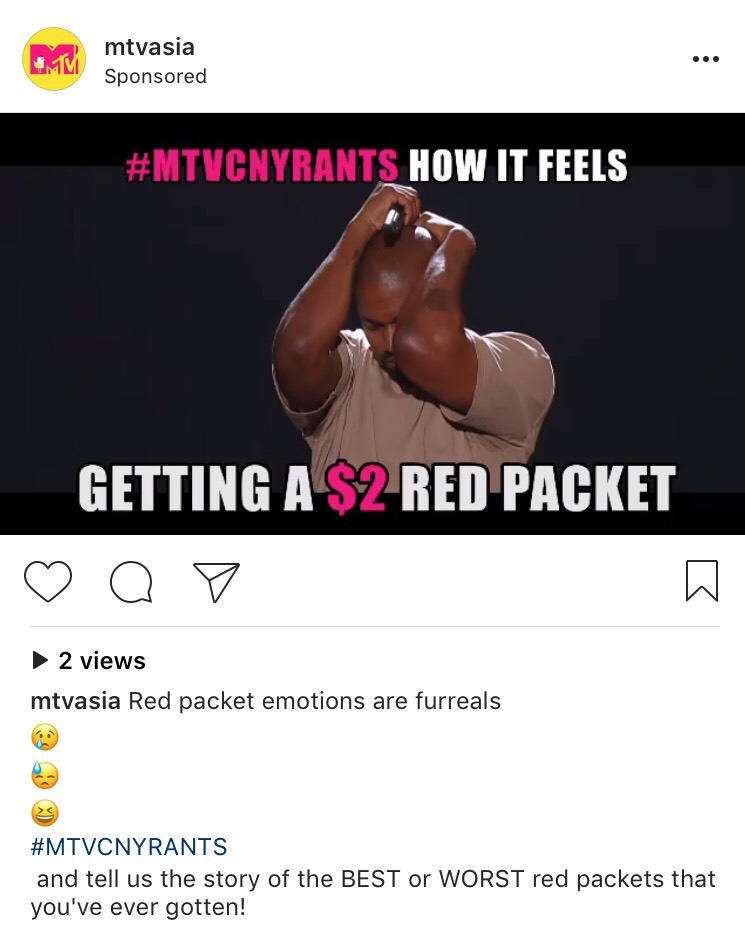

If red packets are all about the gesture, why do $2.00 ones make us feel like such assholes?

There’s knowing that we should appreciate the tradition and meaning behind it. Yet we’re disappointed that it isn’t more money.

“Did I do something to deserve so little? Am I suddenly less equal in comparison to my other cousins?” I might wonder.

More likely than not, I’m just being a greedy bastard.

Because unless you’re a saint, you too have probably felt this way at some point. It’s that familiar, conflicting mess of emotions that comes with receiving a “small” red packet.

In these moments, we realise why we call money the root of all evil.

When it comes to ang bao giving, there’s a huge, complex culture behind it that has become such a mainstay in how we live, we don’t think about it anymore.

This complexity is a very Chinese thing, one largely derived from our need to “save face.”

For instance, I only found out last week that for years, my mother has been asking my sister how much ang bao money she’s been receiving from our relatives. This ensures that she can then put in an equal amount in the ang baos she gives to my cousins.

Basically, she doesn’t want our relatives to think that we’re cheap or worse, ungrateful.

And then there’s that friend of mine whose family makes a show of “prospering” in their professional lives by padding all their red packets with at least $50. Every year, at his family’s CNY gatherings, there’s the same exhausting sibling rivalry to become that year’s favourite aunt or uncle.

He’s told me about years when his family could hardly afford to keep up this charade. Yet it happens anyway, because it’s just what they do every year.

Even now, I still remember what his Dad once said to me when I was still quite young: “Don’t forget to tell your mummy and daddy what a BIG ang bao uncle gave you, okay?”

And the crazy thing is, as kids, we’re just delirious at receiving so much money. As a result, we gush about it to our parents or boast about it to our friends. Unknowingly, we become pawns in this grown-up game of “my dick (salary) is bigger than yours.”

Today, I know that this is a big part of Asian culture. That “keeping up appearances” is almost a universal necessity for many members of older generations.

It’s why there are unofficial “ang bao rates” every year. They’re an informal way to regulate “over-giving,” and to help us manage our expectations. They’re also meant to safeguard against embarrassment from giving too little.

But as Singapore’s economy takes a turn for uncertainty, and more of us are progressing beyond the irrationality of certain Asian traditions, it’s an opportunity to re-think the place of the red packet.

Much like how we secretly bitch about having to ‘bao ang baos’ whenever wedding season rolls around, giving out red packets isn’t always easy either. To some it can be a financial burden, while others might not enjoy having to give so much money to relatives they don’t even like being around in the first place.

So why not just cap the amount once and for all?

Enter the $8 ang bao.

It’s not a lot of money, but for most of us at least, it’s a decent amount.

Being the luckiest number in Chinese culture, it also embodies the gesture better than anything else.

Also, for those who don’t know, 8 is pronounced as ba in Mandarin, which rhymes with fa. This means to gain a fortune. As such, it refers to prosperity, success, and the attaining of social status.

Even though these aren’t exactly nuanced virtues, they’ll do for an occasion like Chinese New Year.

At the same time, while this time of year is all about celebration and decadence, capping ang baos at $8 can only be a good thing.

It evens the playing field, and with everyone knowing that it’s all they’re getting, there’s no room for disappointment. No more guilt or shame for feeling greedy, and certainly a lot less pressure to “save face.”

Which, in any case, is such an irrational thing to do anyway.