To co-opt the opening lines of The Merchant of Venice, “In sooth, I know not why Tanjong Pagar is SO gay?”

When I throw that question around RICE HQ, only one of the esteemed senior staff writers had any insight into the matter.

“Oh, all the gay spaces are in Tanjong Pagar because Lee Kuan Yew will protect us.”

Thanks for that insight, [REDACTED].

In the second half of the 19th century, the establishment of Keppel Harbour would lay the foundations for Tanjong Pagar to become a hub of economic activity. The harbour would eventually disappear over time, but the economic aspirations wouldn’t.

Fast forward a few decades of development, we end up with the Tanjong Pagar we know and love today—chock full of those affluent Ann Siang types.

So far, so straight. As far as the annals of Singapore’s history are concerned, Tanjong Pagar’s colonialism-to-capitalism story is as conservative as it gets.

But if you saunter—I mean if you swagger down Neil Road today like the man’s man you are, you’d find that the stretch of road is pretty, for lack of a better word, gay. A quick gander around the road will tell you why: multiple gay bars—Tantric, ebar, and Outbar, to name a few—exist side by side, less than a hundred meters away from each other along a small stretch of the road. Singapore’s only existing gay club, Taboo, sits along the road among its ‘sisters’, completing the set.

As the night drags on, barhopping revellers hold hands while crossing the road, and the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple looms over them in the distant background, blessing their safe passage across the road and through the night.

Sometimes, friends are made of strangers, and sometimes, they are made into lovers.

Ostensibly, if you know where to look, Tanjong Pagar is a formidable offering of the proverbial wine, (wo)men, and song.

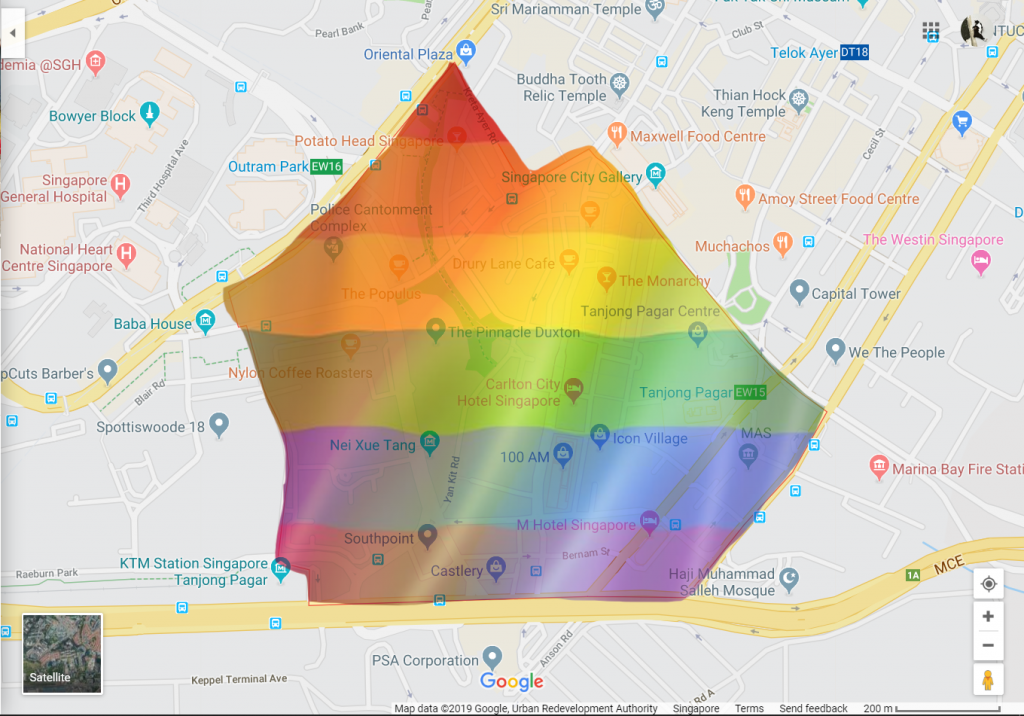

In fact, if you have a diverse range of friends, you’d know that broadly speaking, Tanjong Pagar and its vicinity plays host to a range of gay spaces.

Gay saunas like Cruise Club, 10 Mens Club, and Shogun Club hole up in nondescript buildings, while bars and pubs that broadly cater to a queer clientele are scattered across the locale. The sheer concentration of gay establishments in Tanjong Pagar brands it as a gay nexus—if you will—for Chinatown.

What makes Tanjong Pagar particularly idiosyncratic, however, is the nearby presence of the Police Cantonment Complex and the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum. In the broadly conservative landscape of Singapore, the incongruous mix of legal, religious, and gay urban spaces in close proximity has always seemed like an inexplicable mystery to me.

Do gay policemen working in the Police Cantonment Complex feel strange about the incongruous intersection of their private and professional lives?

Alas, the workplace thoughts of gay policemen in Singapore is something we’ll never know.

But the big question remains: of all places, why did Tanjong Pagar become the defacto ‘gay sanctuary’ in Singapore?

To help demystify the gay mysteries of Tanjong Pagar, I reached out to Kent Low, the professed owner of Singapore’s first gay KTV, Inner Circle.

Mike, the bar manager and Kent’s friend, jokingly introduces himself as the resident ‘courtesan’ or 舞女 in turn and offers to help with the questions. For the rest of the night, he flits to and fro the rest of the patrons and our table, lubricating the social hinges, with charm and wit. Another friend, more drunk than the rest, introduces himself to me twice over the course of the night and repeatedly asks to try on my earrings. At various points, I’m chided for forgetting to toast the table, when I try to surreptitiously sip my drink in a bid to calm my nerves.

Between the entertaining and the booming music, Kent tells me about Inner Circle.

When it opened in 1991 along Tanjong Pagar Road, it was during a time when overt advertising of a gay establishment was unacceptable and would have drawn unnecessary attention from the public or perhaps authorities. In its early days, the nascent KTV relied on word-of-mouth in order to flourish.

But as the “PR person” of the venture, Kent had other tricks up his sleeve.

“My singer friends from Hong Kong flew in to support us,” he says.

“People would excitedly ask me if they were coming, sometimes weeks before in anticipation.”

And in this way, the hype was sustained by word-of-mouth and got business to boom, with the KTV fully packed. In its heyday, the crowd was “three times the size of what you see”, Kent says, gesturing at the crowd around us.

His business partner, on the other hand, was a “shrewd negotiator”; when the KTV underwent renovation, the bar top was constructed for free.

“We didn’t stop operations either—patrons were invited to come in and see the transformation for themselves.”

It sounds slightly amusing at first, but on second thought, it sounds like the kind of entrepreneurial grit and spirit that would have been needed to open and maintain a gay KTV under less than friendly public attitudes.

Business was so good that it would eventually attract other competing gay clubs and bars to the area, helping to seed Tanjong Pagar’s gay reputation.

So why set up shop in Tanjong Pagar?

“KTV has to be somewhere where nobody goes to normally, and rental was cheap,” Kent says.

It’s a surprisingly simple but reasonable answer.

Elvin Poh, the 46-year-old current owner of Outbar, explains, “It all started in the 1990s when gay bars start to run business at Tanjong Pagar Road. Later, maybe because of rental, all started to shift over to Neil Road. Other reasons, maybe rental here, during those days are much cheaper than those in Orchard or Mohammad Sultan or Boat Quay. It is also quite centralised. During those days, being gay is a taboo. Therefore, bosses those days need to find a place that is cheap, centralised and away from the main straight clubs.”

Their answers make sense. 30 years ago, Singapore would have only been in her 20s, with only a cursory understanding, much less acceptance of queerness. Setting up a queer space or, for that matter, a queer nightlife establishment would have required a location away from the prying eyes of a prudish public.

In this way, the story of Tanjong Pagar’s gay history is also a story of economics.

Indeed, as Chris K.K. Tan suggests in Rainbow Belt: Singapore’s Gay Chinatown as a Lefebvrian Space, the proliferation of gay establishments in Chinatown, and by extension, Tanjong Pagar is—in a stroke of irony—the result of state-intervention.

In his account, colonial-era Chinatown was a locale of “gaudy temples, brothels, gambling houses, and opium dens,” and ultimately gained for itself a reputation as a “virulent cesspool of diseases and moral depravity”.

But in a newly-independent Singapore, this would no longer fly; the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) sought to turn Chinatown into a “modern city informed by rationality and efficiency”. To this end, the terraced shophouses and tenement blocks, with their iconic ‘five-foot ways’, were “targeted” for demolition. In the 1970s, calls for the area’s heritage preservation would, however, prompt the URA to make a U-turn and instead initiate a restoration of Chinatown. While the state would plan the conservation project, “private investors executed the actual restoration”.

The lifting of rent controls to encourage the conservation project would eventually set the stage for conservation companies to offer “competitive rents to attract tenants to their newly refurbished properties” in the area.

Savvy queer entrepreneurs like Kent would seize upon this and Chinatown’s centralised location, carving out queer spaces in the form of bars, clubs, saunas and other commercial ventures, with Tanjong Pagar at the heart of it all.

As the initial gay establishments took residence in the area, others would follow suit and sink roots into the area.

“So thinking of the conveniences for clubbers to bar hop in the same area. I believe everyone would have thought of the same way,” he adds.

But history is more than just the broad strokes of capitalistic forces; it’s also about the man—or more accurately, the gay man on the street and how he lived.

At its core, sexuality is about sex after all. Everyone finds an outlet for sexual expression and desire, whether it’s as simple as gushing about your workplace crush, watching pornography, or looking for casual sex. Whatever way we seek sexual gratification, there’s no shame in that.

But for gay men—or queer people in general—the avenues to satisfy sexual expression and desire were far more limited in an era without Grindr, Jack’d, or any other contemporary dating app. Adding to the conundrum would have been a stark fear of exposure, back when attitudes were less tolerant. Cruising would present itself as a solution to these problems, for gay men to seek sexual intimacy in the relative safety of anonymity.

“During the 80s and 9os, the whole area for late-night cruising was centred around the Chinatown area. It started from the quiet back alleys in the Central Business District area including OCBC Building, Hong Lim Park, and Boat Quay where it was conducive for late-night car cruising,” he explains.

“I think it shifted further down China Square then Ann Siang Hill. Alongside these cruising hotspots, spaces of social interactions for gay men like bars and pubs started to appear in the area. Niche, Taboo, Why Not, Inner Circle, and Water Bar. Then came Happy, Mox, Backstage, Play. I remember during the late 90s, the first gay sauna Spartacus opened at South Bridge Road followed by others like Stroke, Raw, and Rairua.”

As Roy Tan writes in his photo essay, A Brief History of Early Gay Venues in Singapore, cruising spots shifted over time as they depended on “poor lighting, sparse human traffic and the presence of dark, derelict buildings or environs”. The gradual redevelopment of Chinatown explains the eventual shift of cruising from the Boat Quay area to the back alleys of Tanjong Pagar’s Ann Siang Hill.

The public cruising would eventually disappear from Ann Siang Hill in the 2000s when the area itself underwent redevelopment with the construction of Ann Siang Hill Park in 2004. But it would further cement Tanjong Pagar’s reputation as Singapore’s ‘gay village’, or as Bobby and his partner Ritz Lim affectionately call it, “our gay ghetto”.

But so what if Tanjong Pagar is so gay?

Outside of nightlife and formally designated social spaces like Free Community Church or Pelangi Pride Centre, informal or commercial spaces of social interaction for the queer community seem to be less apparent. According to local drag queen, Becca D’ Bus, while such spaces do exist in Singapore, there are several concerns accounting for their lack of visibility.

“How many of these spaces want to be publicly marked that way? And how many of these spaces remain safe when they are identified that way?” she says.

The fear of being marked as a queer space arguably boils down to how the public expects queer social spaces to look like in the first place. Media representations have strongly encouraged the association of the queer community with vice and nightlife. Perhaps this has happened to the extent that gay bars or clubs have been normalised in the public imagination, but other spaces of social interaction like a gay bookshop still lie outside the realm of expectation.

Indeed, while something as simple and innocuous as a gay bookshop is common enough overseas, the concept seems foreign in the Singaporean context. A colleague even confesses that while she finds the idea of gay bars to be normal and expected, she found the idea of a gay bookshop in Singapore “surprising” when I brought it up.

This begs the larger question: how should we think about the future of queer spaces in Singapore?

As Bobby says, while “more spaces for queer socialising can only be a good thing,“ it goes beyond that.

“In an era where 377A has systemically erased all positive portrayal of gays in the media, representation matters.”

“We need to be seen more often, beyond the usual after-dark hours of bars and clubs.”

Undoubtedly, there’s a sense of impermanence to Tanjong Pagar’s gay establishments, given their successive opening and shuttering.

As Becca notes, “That’s a description of any nightlife space in this country—some stalwarts that stay for a long time, lots of coming and going.”

Gay spaces, like all other spaces in Singapore—from the cruising hotspots, to the bars and clubs; the spaces that are prominently visible, and those that linger in the periphery of sight—all face gentrification and change.

After all, despite the good business, Kent tells me at the end of the night, that Inner Circle would close around 2003, due to its lease ending and issues with rental increases.

It’s important to remember that the history of queer venues in Singapore did not start with Tanjong Pagar as Audrey Yue and Helen Hok-Sze Leung point out in Notes Towards The Queer City: Singapore and Hong Kong.

Bugis Street in the 1950s and 1960s was one of Singapore’s first visibly queer venues, with its “transsexual sex trade” popular with British soldiers and foreigners in a post-WWII atmosphere.

Later on, the first gay bars like Le Bistro, Treetops, Pebble Bar and Niche would pop into existence along Orchard Road in the 1970s and 1980s.

Yet as we know today, in the march of modernity, these spaces no longer exist, and for the most part, have faded into relative obscurity.

Tanjong Pagar could just as easily follow in their wake one day.

As Bobby says, “It’s important to know the roots and histories of all the safe places, so that we are reminded of the struggles we face every day, how far our community has grown and our culture has evolved.“

“Where we are now, is because of all the people before us. And together, with the people with us now, we will get to where we want to be.”

Singapore Infopedia

A Brief History of Early Gay Venues in Singapore by Roy Tan

Rainbow Belt: Singapore’s Gay Chinatown as a Lefebvrian space by Chris K.K Tan

Notes Towards The Queer City: Singapore and Hong Kong by Audrey Yue and Helen Hok-Sze Leung.

Did you know Tanjong Pagar was so gay? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.