But let’s be honest, you don’t need an ST survey to tell you that. Just look around: whether it’s at the bus stop, on the train, or in line for wanton mee, everyone is pawing aimlessly at their screens. Everywhere are faces of bored contempt, illuminated by the pale glow of Facebook News Feeds and Mobile Legends. Chances are, you are reading this on your smartphone right now, with one hand holding on to the train’s handrails, and the other scrolling down impatiently, wondering, When is this guy going to get to his point?

This might seem extreme, but human beings, as Prof Newport argues, are herd animals hardwired to seek out social approval in the same way squirrels seek nuts. Social media platforms exploit this weakness, by turning your phone into a ‘social validation slot machine’. Every time you post or comment, you are inserting a coin in hope of getting love/attention in the form of likes, shares and karma. This in turn triggers a pleasurable release of dopamine.

Quoting Comedian Bill Maher, Cal Newport likens this process to ‘smoking’. Mark Zuckerberg, in other words, is not a ‘friendly nerd god’, but a ‘tobacco farmer in a t-shirt’.

It sounds a little hysterical, but Mr Newport presents some damning evidence—straight from the mouths of social media tycoons.

Sean Parker, Facebook’s first president, calls the platform a ‘social validation feedback loop which exploits vulnerabilities in human psychology’. Leah Pearlman, the Facebook product manager who invented the ‘like’ button, hires a social media manager to distance herself from her own creation. Tristan Harris, a Google Engineer turned whistle-blower, claims that Silicon Valley is not programming apps, but ‘programming people’.

The results are self-evident. Prof Newport is too classy for the junkie metaphor, but I am not. If half of what he claims is true, our #SmartNation is really a ghetto of tech-addicts, high on distraction.

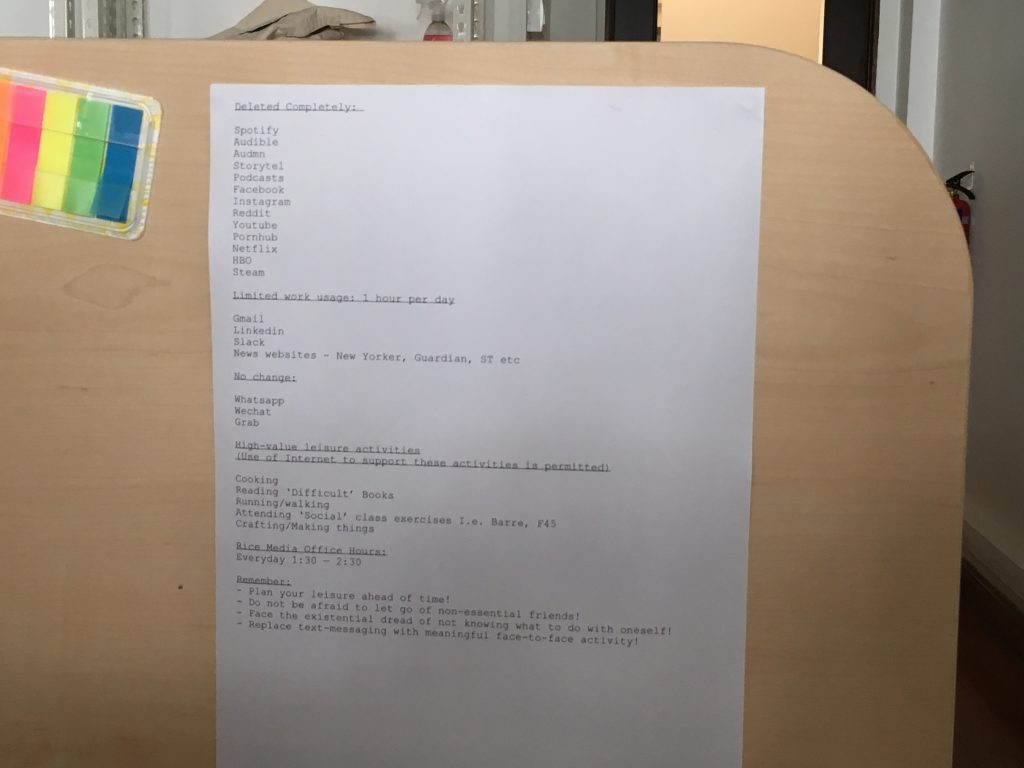

In practical terms, he recommends a ‘30-day digital declutter’ where you remove all non-essential technologies from your life.

Needless to say, I was sold after listening to Prof Newport on my Storytel audiobook. Like most people in 2019, I enjoy a love-hate relationship with my smartphone. Whenever I’m waiting for my train or for the traffic lights to change, I whip out my phone for a hit of that sweet sweet dopamine. Afterwards, I feel guilty, in the same way you hate yourself after masturbation or McDelivery.

After all, who doesn’t want to enjoy ‘increased focus’, better interpersonal relationships and meaningful lives?

For example, an aspiring photographer might continue to share their work on Instagram, but eschew Twitter because it distracts her from photography.

The problem is, I don’t know which apps to excommunicate because I don’t have any deep values—at least not consciously. I don’t want to be a better content writer or to save the world from climate change.

Would be nice if it happened, but you know, I’m just a guy on the internet.

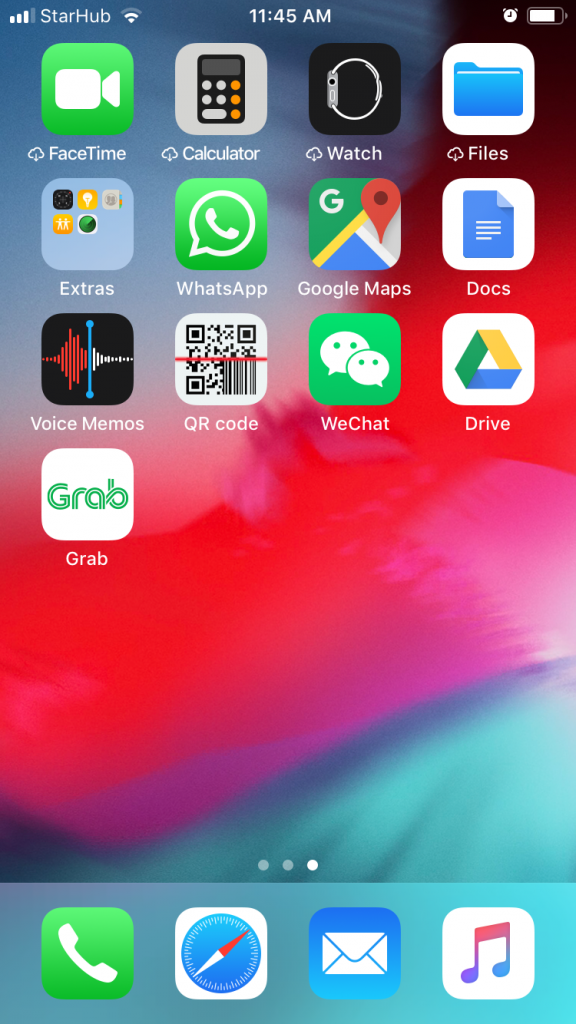

Hence, I end up working backwards. I look at the technologies and imagine what ‘deep values’ they might support. As a result, I end up deleting nearly everything. Not because I desire sainthood, but purely because I can’t imagine what ‘deep values’ could be supported by using Instagram or Netflix.

The only apps left untouched are WhatsApp and Wechat. The former is reserved for professional use, while the latter because my parents are on it. I’ll be damned if some family medical emergency goes neglected while I’m in pursuit of enlightenment.

At 7 PM, I publish an article before heading home. About 10 minutes later, when I’m sitting on the bus, my photographer notices a spelling mistake. I tell him to fix it for me, but he doesn’t have the admin access to the RICE website. I try to log in, but I realise I’ve stored the long and complicated password on Slack, an app which I had deleted.

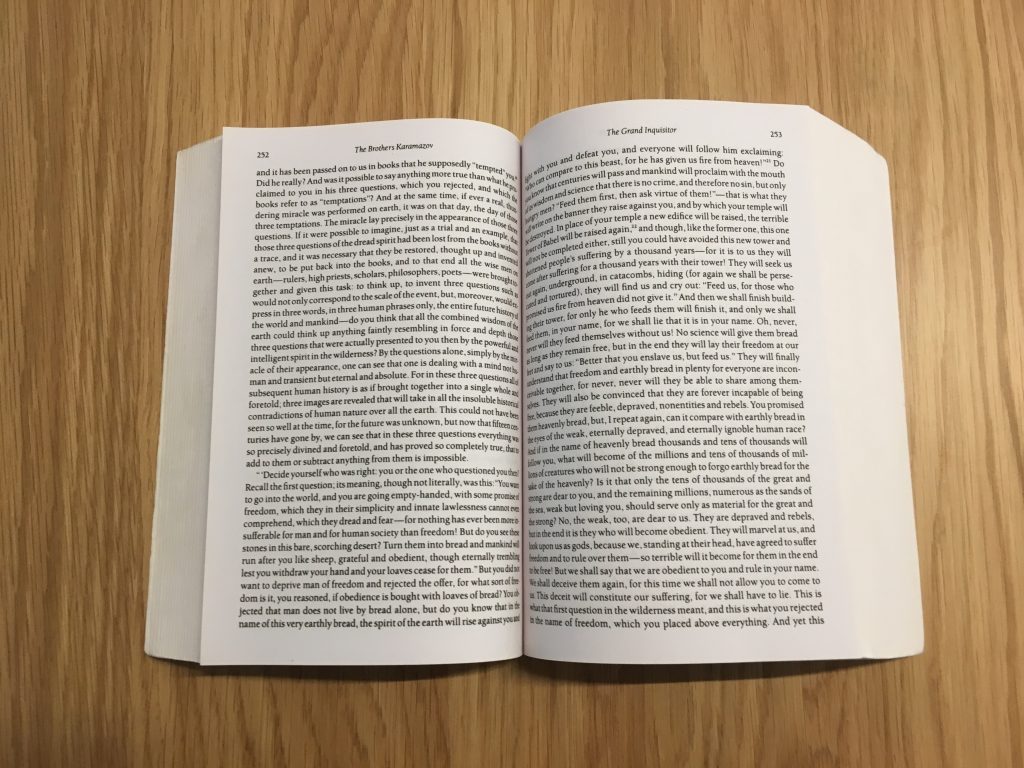

Panic. Chaos. I try to access Slack via my phone’s browser, but I’ve forgotten the login details for Slack because WHY WOULD I REMEMBER WHEN I HAVEN’T LOGGED OUT IN OVER A YEAR. By now, all zen-like smugness has evaporated. I’m cursing God, Cal Newport and myself. It is impossible to focus on reading The Brothers Karamazov because, in my head, I’m imagining the angry Facebook comments and my boss’s displeasure. The one-hour bus ride feels agonizing. When I reach home, I’m in a state of such nervous agitation that I whip open my laptop without bothering to turn on the lights or de-sock my feet.

There is no spelling error.

As it turns out, my editor had fixed it 40 minutes ago, while I was frantically trying to log in. He informed me in a text message which I missed because I had muted Whatsapp.

Video games and Instagram Stories are ‘bad’ because it’s ‘passive consumption’. Reading a ‘difficult’ book is good. Carpentry is better. Social activities like Crossfit are best of all because they provide a ‘supercharged sociality’ of sweaty hugs and boisterous high-fives.

With this in mind, I went to a Barre class because

- a) Crossfit scares me

b) My friend was the Barre instructor so I could join for free

You said it was the last set, 12 SETS AGO, YOU LYING B-[redacted]. I swear to God, I want to punch someone, or collapse on the ground sobbing in the fetal position. Probably the latter because it requires less energy, and anyway, I am already crying; you just can’t see the tears because my face is a Niagara of sweat.

After an interminable hour of indescribable agony, the class finally ends. There are no sweaty hugs or cheerful whoops of joy. Everyone is lying corpse-like on the studio’s expensive teak floor.

Do I feel better? Actually, yes.

Why yes, I do feel better than if I had spent the evening playing video games. Admittedly, gaming is a low barre, but I do feel a sense of pride (for surviving Barre) and camaraderie with my fellow masochists.

Then, something in the studio’s changing room catches my eye: a selfie-ready mirror with #barre stenciled at the bottom. What would Prof Newport say to this? What if your low-value social-validation is used to reaffirm high-value leisure activities like Yoga or Spin?

Digital Minimalism permits the use of digital tools if they are using them to support ‘high-value activities’. You could, for example, watch Youtube to learn the proper Barre posture or how to fix the toilet. But how does this differ from sharing a #barre photo with your #barrebuddies for mutual support?

The distinction strikes me as an arbitrary one, but I’m too tired to care. After a shot of coconut water, I move on.

As it turns out, I had pulled a muscle during Barre. Seeking pain-relief, I shuffle downstairs to the pharmacy like a hip-replacement patient.

This is a good day to lie in bed and watch Netflix. It is the perfect excuse to order KFC and play Stardew Valley on my computer. I desperately, ardently want to, but Digital Minimalism offers no medical exemptions, so I forge ahead onto High-value Leisure Activity No. 2: Cooking.

Prof Newport suggests ‘craft’ as the ultimate ‘high-value’ leisure because it taps into our strong instinct for manipulating objects in the world’. Unfortunately, all of his suggestions are painfully American: fixing your car, carpentry, learn the guitar.

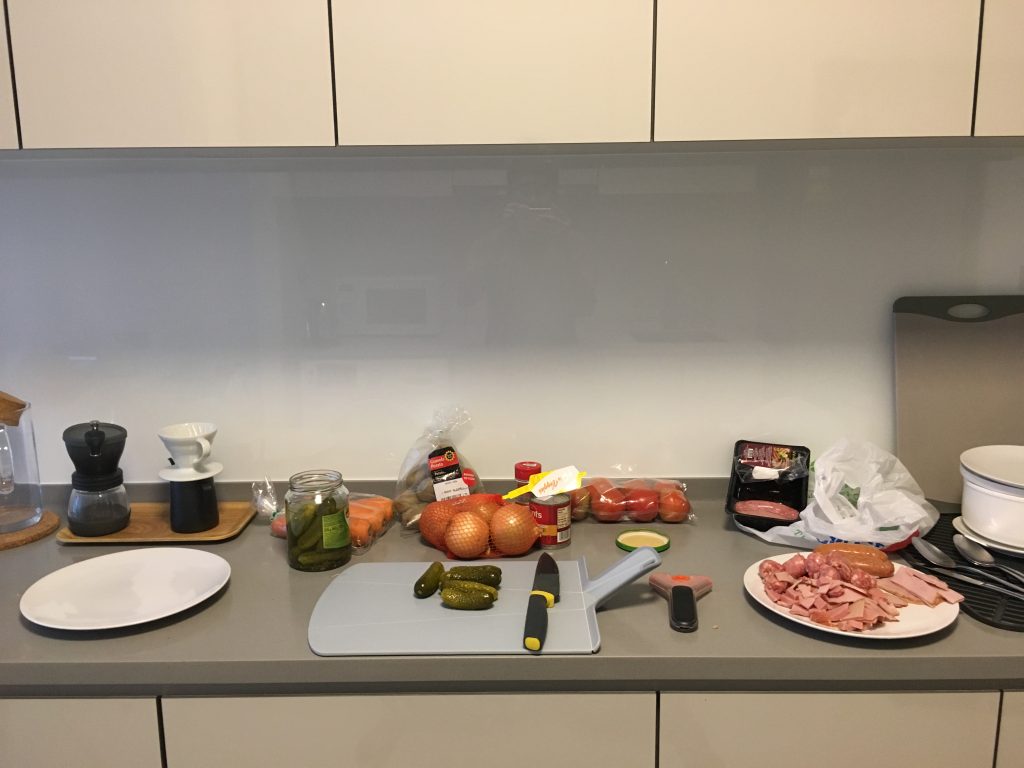

Since I don’t own a car or a guitar, I settle on cooking. To provide some ‘mental strain’, I pick a dish that is relatively difficult: solyanka, a soup of slavic origin which I had been unable to forget since tasting it six years ago in Berlin.

For three long hours, I brown meat, stew tomatoes, grind pepper, and cut approximately 9000 different vegetables into tiny, OCD pieces. It’s not difficult, but the prep is longer and slightly more complicated than the history of Russia itself. Halfway through cooking, I have to stop and wash dishes because I’ve run out of plates for my diced onions, pickles, carrots, sausages, ham, potatoes—pause for breath—beef, sour cream, dill, and bay leaves. There is supposed to be a deep mental satisfaction to be gleaned from this, but all I feel is the pain in my arse and a sense of boredom as my weekend dissolves in a sea of sausages and pickles.

Normally, I would stave off boredom by listening to music or an audiobook while dicing onions. However, Mr Newport advises against this. Those earbuds interrupt ‘time alone with your thoughts’. They result in a ‘solitude deprivation’—a state in which your own mind spends close to zero time with your own thoughts, and free from input from other minds.

This is, perhaps, the most miserable part of Digital Minimalism for me. As an audio addict of the first order, my every waking hour is filled with noise. Some men pay beautiful women to touch their genitals. I pay people to tickle my eardrums as I walk home or cook dinner. My favorite activity of all time is to go for long, pointless walks so I can listen to an audiobook, returning hours later both exhausted but illuminated.

This absence of sound is sorely missed. Watching my tomatoes simmer in near-total silence, I feel not just bored, but desperately, existentially lonely. As if the whole world had shrunk into the contents of my stew.

It is so painful that I turn into a needy person. I call my friends to ask when they’ll arrive and they answer wearily: ‘Check your WhatsApp’. When they do arrive, I talk too much and laugh a little too loudly at every joke.

But for good reason.

Even for someone baptised into the rigours of Russian literature by way of Tolstoy and Chekhov, TBK is headache-inducing. It is probably the only novel in the world which uses more exclamation points than commas. Everyone is always either making passionate speeches, running distractedly out of rooms, or having intense philosophical debates about the soul.

Nobody talks about the weather or what to eat for dinner; everyone talks endlessly about God.

And yet, it’s not uninteresting because the characters behave in ways that are contradictory but unexpectedly true-to-life.

Unfortunately, it’s a novel that requires a lot of focus—just to keep track of those confusing Russian names. After a long day of staring intently at my screen, it’s hard to stay awake whilst staring at a wall of printed text. Instead of ‘reclaiming leisure’, I end up falling asleep….

The book is filled with such testimonials. There’s Dave, a creative director who found meaning by limiting his Instagram use and there’s Daniel, who has a better relationship with his wife.

My name is not on that list.

Instead of becoming more serene after adopting digital minimalism, I became less happy, less focused, and slightly unhinged, not unlike certain characters from Dostoevsky.

In the absence of online distraction, I did not become a more productive, more capable writer. Because there is nothing inherently modern about the idea of procrastination, I came up with ‘story ideas’, bought ‘snacks’ for the office and scribbled nonsense into presentation decks under the guise of ‘helping out with pitch work’—all in an effort to avoid the unpleasant task of actual writing.

In the absence of the usual WhatsApp to-and-fros, I did not end up having deeper, more meaningful conversations. Instead, I tore around like a bored encik, annoying everyone with my shower thoughts.

Worse of all, I did not enjoy the solitude and introspection that Cal Newport deems good and necessary. It might have worked out for Abraham Lincoln or Albert Einstein—solitary role models in Mr Newport’s book—but not for me. In the absence of music and sound, I am left alone with the person I hate most: me. The thoughts that enter my head are not happy and contented reflections on a day well spent, but Iago-like voices of self-doubt and despair.

Instead of letting workplace difficulties go, I obsess over tiny mistakes, long-forgotten conversations, and imagined slights. Anxiety followed me to sleep like a bad smell.

Deleting WhatsApp seems like a good way to cut your employer’s digital leash, but it’s a meaningless gesture unless you free yourself from the expectations they represent. If not, by allowing emails and deadlines to follow you home and occupy your thoughts, you’re actually working even more.

In The Pleasure And Sorrows of Work, Alain de Botton wrote that coffee and wine are essential beverages for the office worker because they provide the hard take-offs and soft landings that make white collar life bearable. I would argue that Instagram or Youtube function in the same way. They massage the tension from your mind and enable you to unwind.

Cal Newport himself makes the case for this in his earlier book Deep Work: Rules For Success In A Distracted World. There, he preaches against social media, because our mind will dwell on these distractions even after we close the tab and return to work.

However, the reverse is also true. We can also dwell on work at the expense of leisure. So why shouldn’t we purge those thoughts by means of Reddit or Netflix? The argument ought to cut both ways, but it doesn’t.

At home, I play 2 hours of DOTA until all the tension has been drained from my body and redirected towards my imbecile teammates. After some Chamomile Tea and ASMR, I fall asleep feeling more contented than I had ever felt in weeks.

The next morning, I did not bother to purge my phone of these apps. I ended my digital declutter, in the same place where I had started.

His critique of the Social Validation Industrial Complex is, likewise, savage and utterly convincing. I am sold on his version of recent history; where the iPhone began life as an ‘iPod which made phone calls’ before evolving into a portable roulette, whose main purpose is to capture an ever larger market share of your attention/time for the benefit of advertisers or Russian bots.

Although he only devotes one or two chapters to The Evils of Digital World no one can read it without being disabused of their belief in Silicon Valley’s self-proclaimed benevolence.

However, that much has been clear for quite some time. What separates Mr Newport’s condemnation of the Digital Life is that he prescribes a regime to combat these ills. Alone amongst the whistle-blowers and defecting Twitter executives, he remains one of the few who believe that we can fight back by doing a Marie Kondo of the mind.

Distraction is not inevitable, and through sheer willpower, we can restore deliberation and intention to lead a more meaningful life.

This is where he loses me because I find this solution trite and fundamentally flawed. The idea of replacing distraction with intention, and working from your ‘deeply-held values’ sounds very reasonable, but it’s utterly unworkable for losers like me who don’t have any ‘deeply-held values’ or grand ambitions currently being hindered by excessive Facebook usage.

“Intentionality is satisfying”, Mr Newport preaches, but this argument is only true if you are a type-A ladder-climber with goals in mind and many miles to go before you sleep. If you are someone like me, who’s just happy to get through each working day, intention is merely another chore.

Therein lies the basic mistake of Mr Newport’s philosophy, in my view. Social media is not distracting us from a more meaningful life. The lack of a meaningful life is what draws us to social media in the first place. In the absence of a firmly-held purpose/belief, nothing can save you from distractions, whether analogue or digital.

It is often said that young people use their phones too much. We suppose this is because they ‘grew up with it’ as ‘digital natives’. It occurs to me that maybe—just maybe—it’s not their familiarity which undergirds their addiction, but youth. If you’re sixteen, unsure of yourself and don’t know what to do with your life, you are more likely to waste your time on Instagram, seeking approval. It is the same reason why so many older people are drawn to Fake News, Candy Crush, and Pokemon Go.

The absence of intention is the egg, and digital distraction is the chicken.

Cal Newport, however, cannot furnish your life with a purpose. He can help you get to your destination, but he cannot help if you don’t know where to go.

Before Digital Minimalism, I was a smug asshole who considered myself better than everyone else purely because I moderated my meme intake and spent a miserly 1.5 hours on my phone everyday. After being baptised into the Reformed Church of Newport, I realise how reliant I was on my games and audiobooks. Without these distractions to while away the quiet moments, I became restless, bored and existentially, dreadfully lonely. I became unable to function and quickly relapsed.

Just as an alcoholic is not defined by the amount of alcohol he/she consumes, the digital addict is not defined by the amount of screentime imbibed. You can use your phone for 40 minutes each day, but it’s still a compulsion if your life falls apart without those 40 minutes. In short, I was a smartphone addict just like my friends, even if my use was sparing in comparison.

The challenge then, is to find one’s deeply-held values. For that, no self-help philosophy can really help. This is the hard part, because to quote Dostoevsky, who wants to be “one of those who live their whole lives without finding themselves in themselves”?

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport is available on the Storytel App, a subscription-based audiobook platform.

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky is also available, but do get some sleep before listening.

Rice readers get a 30-day free trial, so download Storytel to get started, and check out over 110,000 titles they have available for streaming or download.