Does your pulse race? Does your chest tighten whenever you hear the familiar ‘ping’ of a WhatsApp message? Or maybe you look forward to it—a shot of dopamine coursing through your veins every time you shoot off another hot take on Twitter?

Gwyneth used to be super active on social media. (To some, she probably still is.) But over the years, she has become increasingly cautious.

Now 23-years-old, she has been using the big three (i.e. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) since secondary school. She eventually lost interest in Facebook, even deleting her account. She remains active on the other two apps, but not-so-pleasant experiences have soured her appreciation of the platforms.

Gwyneth describes how one of these incidents started with the Monica Baey saga. She noticed that there was a lot of discourse and conflicting messages from multiple parties.

“We had people making certain claims online, the university released statements that seemed contradictory, and news reports were giving scattered information via updates that made the whole situation chaotic.”

Frustrated at the state of affairs, she posted an “expletive-laden rant” on Instagram.

But the internet isn’t our personal diary, as much as we want to believe so. The next thing she knew, someone had taken a screenshot of the post and sent it to her superiors in school. This is unbecoming behaviour of a student leader, they said. She should be punished accordingly.

“It was very jarring for me because my account was actually private at the time,” Gwyneth says. “That told me that it was someone that I knew, and probably trusted.”

“I struggled with this for a long time. I felt betrayed and upset. At the same time, I was wondering, is it right that I am behaving like this? To what extent can my online persona be generalised to me in real life?”

Paul, 26, is a self-described “digital native” and an active Twitter user.

“Sometimes, it feels like certain arguments on Twitter resemble a class discussion, where you have someone who didn’t do the readings just playing devil’s advocate in order to score participation points,” he explains.

Indeed, Twitter often gets a bad reputation for facilitating very incendiary, reactive posts. In May, it even tested a ‘rethink your reply’ feature, where tweets that contain harmful language would be flagged with an option for users to revise them before being published. Just this month, they added a feature that limits who replies to tweets, similar to how Facebook allows users to restrict comments.

Paul adds, “Twitter, like other platforms, can have ‘bad faith’ actors who are there just to stir shit or leave an instigatory comment, and not bother to follow up on it or engage with people in any meaningful way.”

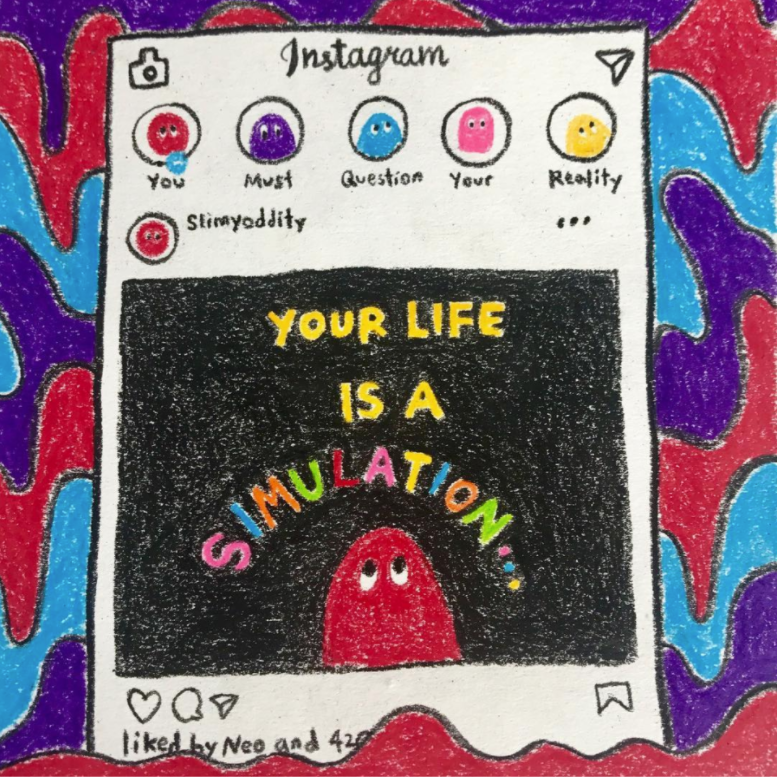

Much of this is a result of how social media, including Twitter, favours content that is short, snappy, and (sometimes) provocative.

Even if you can technically post your entire dissertation on Twitter/Instagram/Facebook, the chances of someone actually having the patience to trudge through it is almost zero. A provocative one-liner will get far more likes and reposts than a thoughtful, nuanced essay.

Dr Geraldine Tan, psychologist at The Therapy Room, explains, “If I get into a verbal fight online with a person that I do not know, half of it is in my fantasy world. I’m fighting someone I created in my mind that is—pardon my language—a bastard. So he deserves to be screamed and shouted at online.”

At the same time, we imagine that our online avatar grants us some level of anonymity (even though our personal data is literally right there for any low-brow hacker to scrape). This “fantasy” that we create also makes it much easier to get riled up in the first place, because the consequences simply aren’t as tangible.

“If I’m looking at you, I still can see your expression,” Geraldine explains. “But when I put something online, I cannot see your expression.”

“So the magnitude of it when we don’t restrain ourselves can be more than [when we are] face-to-face.”

Social media interactions literally activate our brain’s reward centers. Every like, every comment, every new follower—they all deliver that lovely rush of dopamine, keeping us addicted and coming back for more. Some people even tie their self-worth to the number of likes they get, Geraldine adds.

But Paul argues, “I think people overstate the point that social media is an echo chamber. While social media can create echo chambers, we forget that it is a tool that extends from real life, amplifying parts of it that already exist without the facilitation of social media.”

Even without social media, we are more likely to gravitate towards people with similar worldviews in real life to begin with. Psychology—and, increasingly, popular culture—has a word for it: confirmation bias.

These echo chambers, which are already present in some form, translate to and are strengthened by the online world.

Gwyneth agrees, noting that, despite the diversity of perspectives available on social media, she’s not sure if she has actually become more open-minded because of it.

For example, she follows pages about women’s empowerment and about uplifting marginalised groups. She acknowledges that they build upon her existing knowledge, giving her a more nuanced perspective on different issues.

“But I am not exposed to the opposing perspective, maybe like anti-social justice. And sometimes when I see opposing comments, I don’t actually want to engage.”

Furthermore, online disagreements rarely involve just two parties. “There are at least two people who disagree, but there’s the audience also,” Gwyneth points out. “People who are silently watching this whole thing unfold, and they bring with them their own biases and perspectives.”

Spectators are just as important. They judge whether or not the debate is worth engaging with, and have the power to increase its visibility by participating, or even just liking and sharing.

“I think that’s how social change happens, when the majority finds that actually something is not right with the current status quo. We have to get together and make something better.”

Confrontations that were once more straightforward and temporary are now immortalised online. The screen enables us to engage in a way we might not do so in real life. And all these disagreements, these debates and dialogues and conflicts, are weaved in with the echo chambers that we exist in, and involve more than just two dichotomous parties.

Perhaps, then, disagreeing isn’t always about picking a winner or even coming to a middle ground.

“Too many of us see conversations as a debate in which one side has to win. We need to be aware of forms of conversation that involve laying our opinions out on the table, digesting what we’ve all brought to the potluck, and telling each other what we think without having to award a winner,” Paul adds.

“Of course, this doesn’t mean that everyone has equal rights to certain opinions. If your dish is raw and undercooked, then obviously we shouldn’t hesitate to prevent dinner guests from getting food poisoning.”

With the sheer visibility of social media, and its power to galvanise a critical mass, the goal of disagreeing or online discourse—barring those who are clearly there to stir shit, like ‘bad faith actors’ or ‘trolls’—could then be to merely share our perspectives.

Ultimately, even the most controversial topics on social media will fade away eventually. What truly matters is the people who remain and move conversations forward; who engage without prejudice, building open communities that allow voices to be heard and drive tangible change.