I might not continue the tradition of the annual Chinese New Year reunion dinner with my extended family once my elders pass on.

I can’t speak for every blasphemous individual, but the sole reason I don’t appreciate reunion dinners is simple: I am not close to my relatives. We’re on different wavelengths, have zero hobbies and interests in common, and share no overlap in our social circles. If we weren’t related by blood, I doubt they’d be in my life.

Still, I do it every year because I respect my elders and their wishes to see the entire family get together. And for the most part, I’ve learnt to love—okay, tolerate—the obligatory gathering. After many years of dreading the few hours in the evening where the mind-numbing small talk is enough to give me an aneurysm, the angst has given way to acceptance.

While I haven’t cared enough about the tradition to buy new clothes for Chinese New Year for over a decade, I was determined to investigate the validity of my sentiment towards reunion dinner and prove I wasn’t alone.

After all, many of us regularly complain about various microaggressions from relatives that anyone would objectively believe we’d rather do away with all mandatory customs if we had a choice.

The bad news is, I hate being proven wrong.

Of the remaining who do, the top two reasons for attendance are years of tradition and familial obligation, making me believe the respondents are like me—passive-aggressive complainers who can’t find a legitimate reason to back out of the inescapable family gathering, hence show up just to count down the minutes till they can head home.

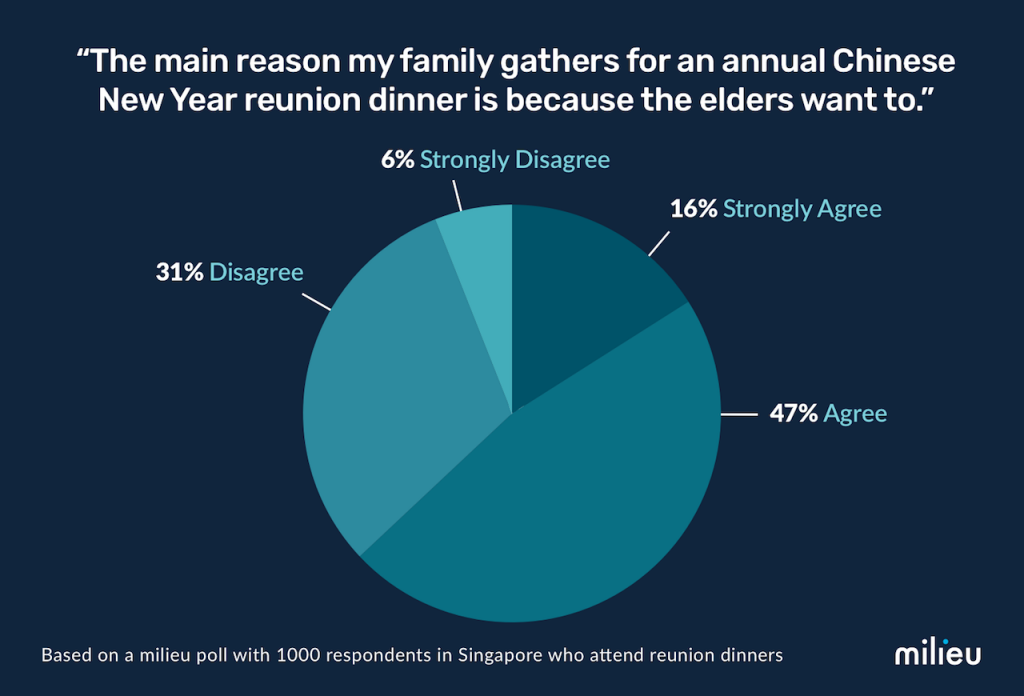

This appears to reinforce tradition and obligation as the core reasons that we still bring ourselves to see the people whom we wouldn’t see any other time of the year if we had a choice.

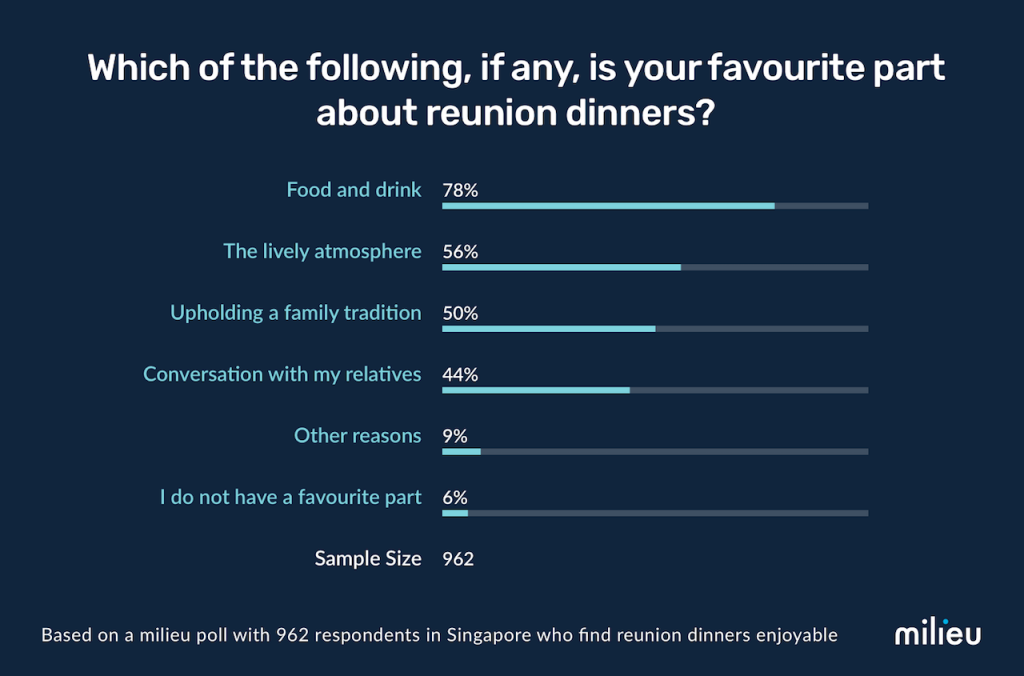

But what’s unexpected is exactly half the respondents feel that “upholding a family tradition” makes the reunion dinner enjoyable.

To the average millennial, one would assume “tradition” is associated with tedious, stuffy, and antiquated perspectives or ways of living. According to the poll, however, “tradition” might carry an inherent sense of pride, responsibility and duty, or even love, ensuring we desire—and even enjoy—upholding said tradition.

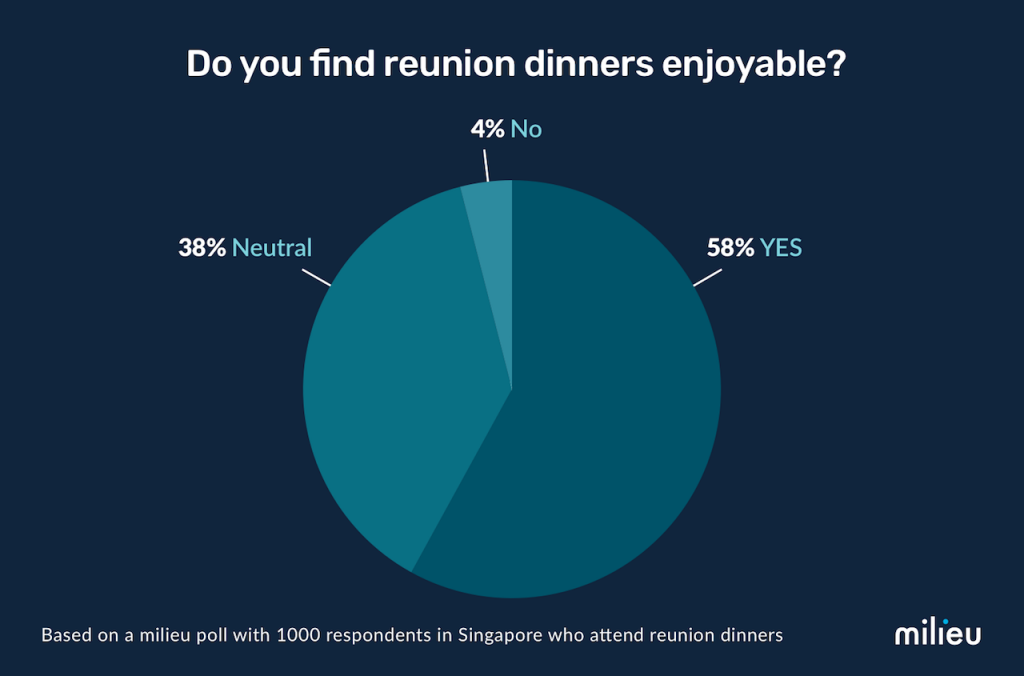

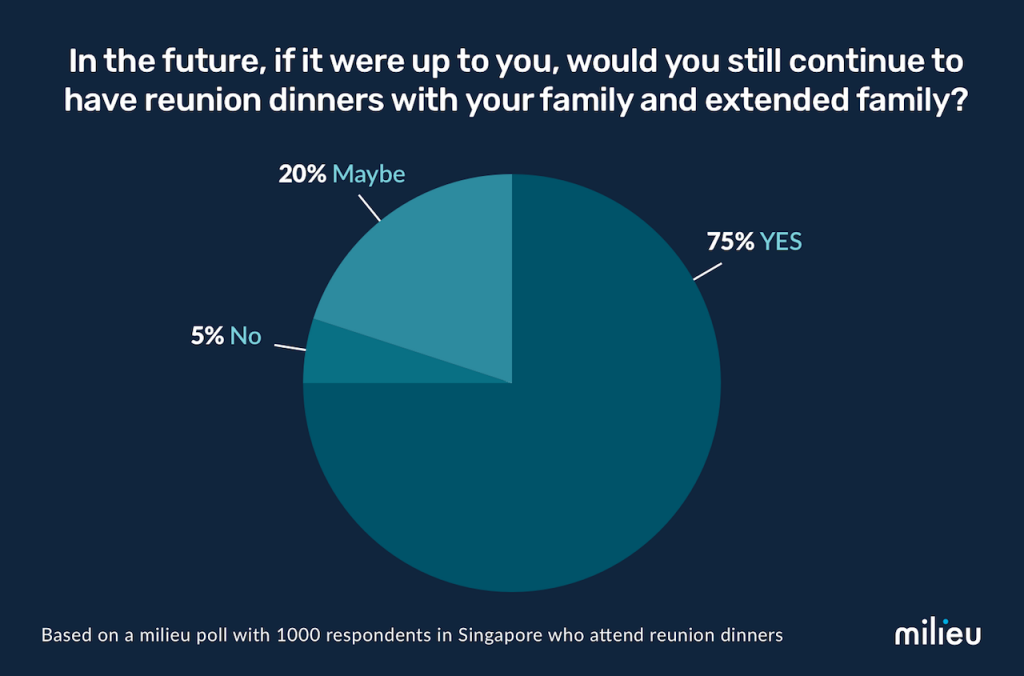

Only 5% said they wouldn’t hold a reunion dinner—noticeably around the same percentage of respondents (4%) who mentioned they didn’t enjoy reunion dinners in an aforementioned infographic.

Whether you’re like me (i.e. on the fence about seeing your extended family) or categorically dreading tonight’s reunion that no amount of food and drink will sway you, this piece isn’t meant to shame or guilt-trip you. Many of us have understandably complicated relationships with our families that few others are privy to.

But as I’ve discovered over the last three decades, your relationship with your family—and anyone, really—inevitably changes as you change. You might not be able to move mountains or singlehandedly abolish years of unquestioned tradition, at least not without potentially being branded as the black sheep of the family, but you can change your perspective towards tradition.

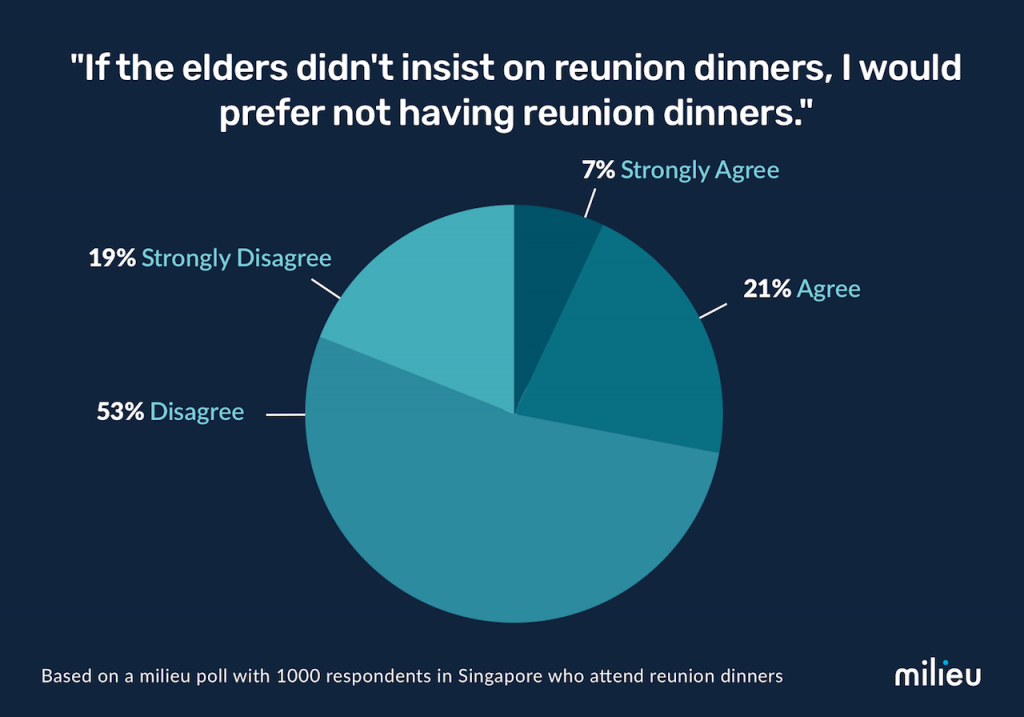

Although the conventional belief that “tradition” and “familial obligation” make attending reunion dinners a downright chore, it appears we like attending reunion dinners for these very reasons, as the poll results show. We like doing things that make our elders happy, such as dressing up and showing face, even if we might not genuinely and completely want to be there.

In the end, even the most anti-social of us might conclude that a reunion dinner only happens once a year, so there’s no reason we can’t give our elders a fond memory for the next 364 days.

In the spirit of Chinese New Year, there might be nothing else that brings forth more joy than making others happy.