This story very nearly didn’t happen, because I kept falling asleep every time I tried to write it.

It wasn’t just writer’s block. I’d open up Google Docs and stare at the screen, only to give up one or two limp sentences in and go in search of coffee. Or I’d get back from work, open up my laptop, and pass out.

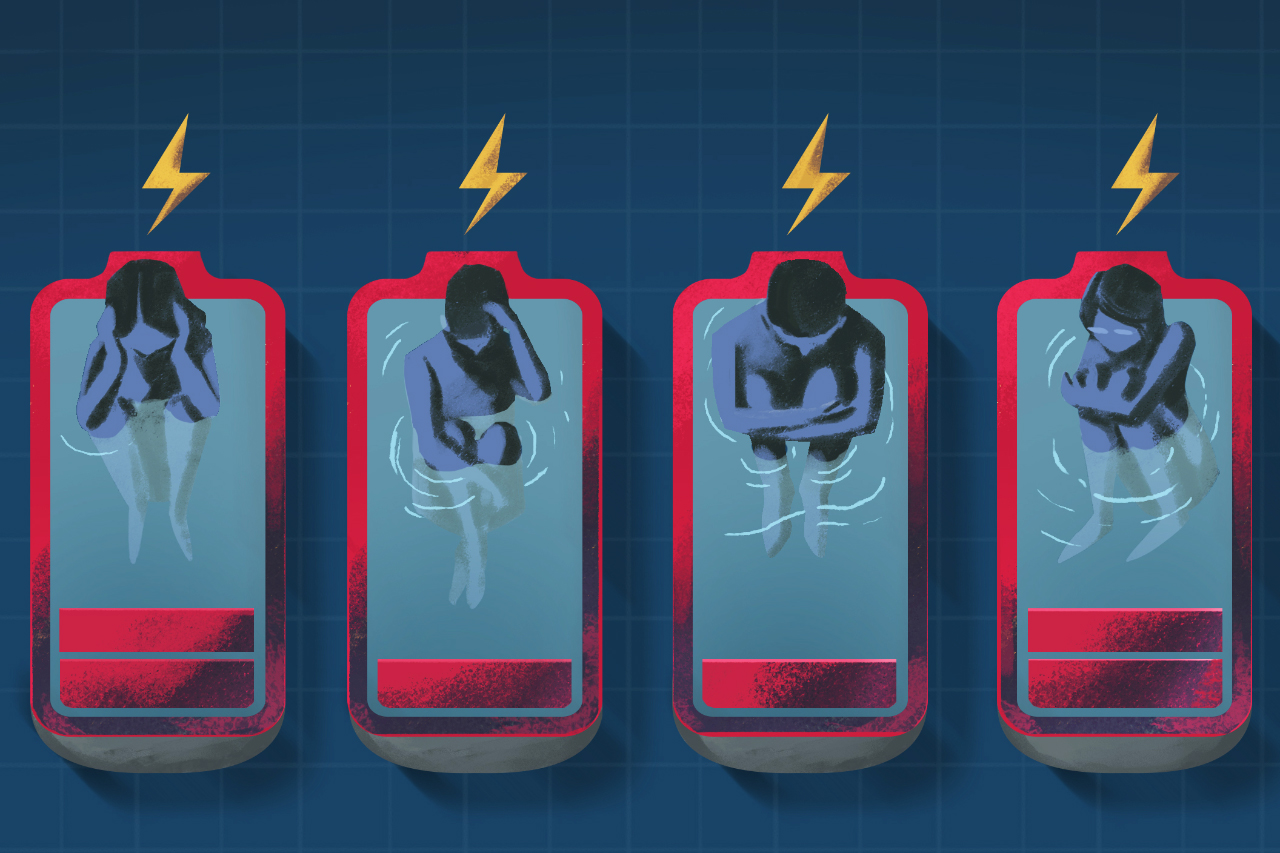

Most of the time, summoning a thought felt like I was groping through the densest, darkest parts of the ocean; it was as though my brain had been replaced with fog that no amount of caffeine or deadline panic could penetrate, lingering long after I’d closed my laptop.

Often, this extends beyond work. Everyday things seem to take an inordinate amount of effort. Remembering dates and names and random-but-important facts. Staying present during meetings and conversations. Speaking in coherent sentences. Finishing them. Getting out of bed.

Sound familiar?

When I finally kept my eyes open long enough to take a look around, fatigue seemed to be everywhere.

It was in the wan faces on the MRT at rush hour, and emails that took three times as long as they should to write. It was in Post Malone’s ‘Always Tired’ face tattoo, and the reflexive rise of self-care. It was in zoning out mid-conversation and waking up already feeling run down, and always, always feeling like you could get so much done if you didn’t want to take a nap all the damn time.

Ironically, when I brought up the topic with friends over dinner, everyone perked up in recognition.

“It sucks,” said one. “I’ve literally gone out to meet friends and just ended up resting my head on their shoulder and saying, “Sorry, I’m listening, I’m just really tired.” It’s definitely affecting my health too.”

All around the table, heads bobbed in agreement.

Several days later, another friend posted the following status update:

Them: “What words would you use to sum up 2018 so far (e.g. ‘blessed’, ‘happy’, ‘sorrow’, ‘love’, ‘heartbreak’)?”

Me: ‘Damn tired’ and ‘eat what?’

If it weren’t so sad, it’d be hilarious: for people supposedly in the prime of our lives, all we want to do is crawl back into bed.

To some extent, this isn’t exactly a new phenomenon. Singaporeans and poor sleep go some way back. A quick Google search of ‘Singaporeans and exhaustion’ turns up a list of newspaper articles from the last decade or so, cataloguing our troubled relationship with sleep: ‘Tired of feeling tired?’; ‘Singaporeans not clocking enough sleep’; ‘60% of Singapore workers feel mental fatigue at work’, and so on.

Of course, the causes of fatigue can be manifold. According to Dr. Lim Boon Leng, a psychiatrist at the Dr. BL Lim Centre for Psychological Wellness, many cases of poor sleep are caused by an underlying psychiatric or physical condition, like sleep apnea or impaired thyroid function. And as anyone who’s dragged themselves to work after a night out will recognise, Dr. Lim confirmed that poor sleep can cause anxiety, irritability, poor concentration, and fatigue—all of which can escalate into depression or anxiety if left untreated.

That said, the pervasive tiredness so many of us are dogged by doesn’t appear to have a distinct medical cause. If anything, it often doesn’t seem serious enough to be anything more than privileged grumbling, let alone a ‘real’ problem warranting medical attention.

It’s not quite a medical issue, and yet more than being run ragged from overwork. The roots of millennial fatigue seem to lie instead in a mix of unavoidable cultural and technological shifts over the last decade, when most of us came of age.

That, and if we’re being completely honest, some of our own bad decisions.

On one level, the causes of this epidemic are structural; the unavoidable collateral damage of living in this day and age.

For example: we can’t disconnect, because smartphones, email, and messaging apps didn’t just change the way we communicate; they’ve effectively rendered us on-call 24/7, both in our professional and personal lives. Not only has the concept of ‘after hours’ become all but moot, being ‘always contactable’ is often conflated with being ‘always available’.

Expectations have evolved at all levels, from clients making last-minute requests to ‘unofficial overtime’, like WhatsApp discussions about work that continue long after leaving the office (particularly in smaller business environments, where work processes can be more informal). Similarly, we think nothing of receiving texts from friends and family throughout the day (or texting them ourselves), be they about weighty personal matters or someone sharing yet another meme to the family group chat.

This is the technological equivalent of a stream of people banging on your door at all hours of the day, and it’s just as mentally draining. Even if you choose not to answer immediately, you can’t tune everyone out.

We’re all intimately acquainted with the tyranny of the blue ticks—all those messages you’ve left ‘for later’ nagging away at the back of your head, elbowing you in the brain, reminding you that they’re still unanswered.

Similarly, we’re constantly distracted and overstimulated, at the cost of our ability to focus. The detrimental effect of tech on our attention spans has been getting a lot of press lately, and for good reason: it’s designed to make us behave like five-year-olds in a candy store.

As experts have pointed out, there’s a legitimate explanation, known as Directed Attention Fatigue, for why always being distracted is so draining.

Human attention manifests in two ways: as ‘directed attention’ (the ability to focus on tasks requiring conscious effort, like reading a book), and ‘involuntary attention’ (which governs our responses to unexpected stimuli, like a notification popping up on your phone). The problem is that we only have a limited capacity for directed attention, and as anyone who’s found themselves flagging as the day wears on will recognise, the more things there are competing for our attention, the quicker we end up depleted.

We’ve also had a lot to worry about lately.

The rising cost of living and whether we’ll be able to afford a BTO. The devastating impact of climate change. Whether our jobs will still be around ten years down the road, and whether we’ll be equipped for them. Whether we’ll be able to look after our parents when the time comes. Moreover, within the last few years, many norms we grew up taking for granted have been interrogated and turned on their heads: race, gender, consent, meritocracy, and success, just to name a few.

None of this is to say that becoming more critically engaged and thoughtful citizens is undesirable—far from it. However, learning to navigate adult life at a time when so much is uncertain can contribute to us feeling anxious, disempowered, confused, and ultimately, exhausted.

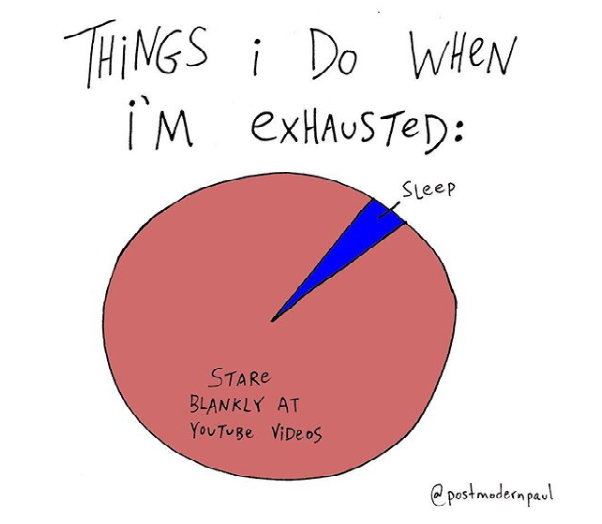

All this being said, we also tend make some poor decisions around how we manage our exhaustion.

Take, for example, the creep of our phones and laptops into our beds—scrolling through Instagram or watching an episode of Modern Family to help us ‘wind down’ before turning in, despite the copious amounts of research pointing to how these activities actually keep us up. Habits like these don’t just throw our circadian rhythms—the biological systems governing our sleep cycles—out of whack; blue light of the kind emanated by our screens inhibits the production of melatonin, a hormone which encourages sleep.

Or how, despite the emergence of the wellness movement, we’re still not all that good at self-care. Many of us eat terribly, don’t get enough exercise, and medicate with alcohol or coffee.

It’s a recipe for disaster. Take our often rich and carb-heavy local diet, combine it with schedules that can leave little time or inclination to exercise, add in a drink with friends to take the edge off a long day, and top off the mix with a coffee (or three) the next morning.

The result: we’re broke, hungover, dehydrated, and to add insult to injury, still tired.

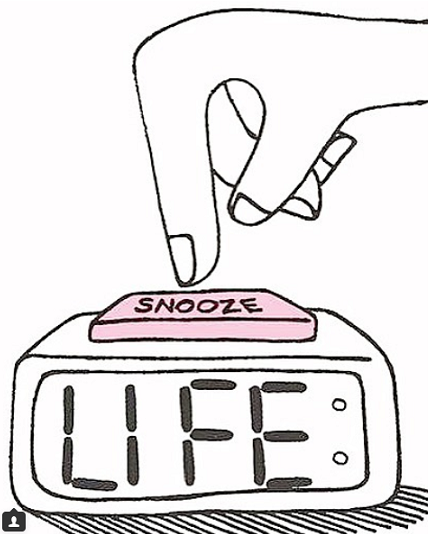

Last, but perhaps most vicious, is how we took out memberships to the Cult of Productivity.

The Cult of Productivity is, in a sense, the ugly cousin of the carefully nurtured Singaporean work ethic. Despite the name, it actually has nothing to do with working smartly or efficiently. It’s ego and insecurity souped up with a dash of FOMO, an obsession with having it all, and the urge to prove that we’re doing life right by squeezing every drop of it out of our 24 hours.

To this end, how tired we feel, and how much we advertise it, have become directly proportionate to how meaningful we think our lives are.

We’ve all seen this in some form or perpetuated it ourselves. Engaging in competitive bragging about how late we stayed last night or the worst all-nighter we’ve pulled or how little sleep we can function on. Sending emails at stupid hours of the night just so our bosses know how hard we’re trying; posting Instagram stories of bringing our laptops on vacation, or the fluorescent glow of empty offices at night, proclaiming, “Last one here!”.

Fetishising coffee addiction, productivity apps, and having a side hustle. The rise of slogans like #cantstopwontstop and the proliferation of ‘How I Get It Done’ listicles, written by people whose lives are so earnestly jam-packed they read like parody.

To this end, even if you don’t subscribe to the Cult (or think you don’t), you’ve probably felt its reach in some form. For example: seeing posts by people whose days are so busy just reading about them makes you tired, worrying you’re not doing enough, and then wallowing in self-doubt until you fall asleep.

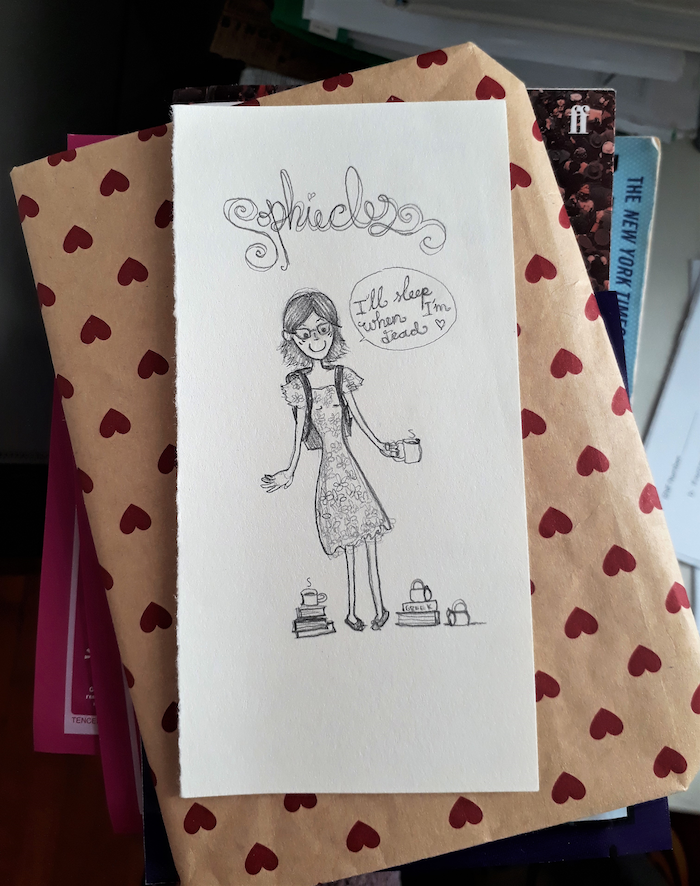

At this stage, I should own up: I’m a member of the Cult myself, and have been for years. Back in university, I was notorious amongst my friends for sleeping just two or three hours a night, between going to classes, attending extra courses, participating in several extracurriculars, volunteering, hanging out with friends, going on dates, and completing my readings in time for the next morning’s 9:00am lecture.

At one point, a friend drew a little sketch of me surrounded by piles of books and empty coffee cups, proclaiming, “I’ll sleep when I’m dead!” Not sleeping had become a point of pride; it was my way of signalling that I was disciplined, industrious, of advertising that I’d managed to enjoy an active social life while keeping up my grades.

Obviously, the reality was much less glossy. The truth of it was that I was all of twenty years old, in good health, privileged enough to be financially supported by my parents, unencumbered by adult responsibilities, and with no concept of my own limits.

The upshot of all this is that how we talk about tiredness is shifting.

We’ve already normalised it without even noticing; as my editor put it, somewhere along the way, we went from replying to “How are you?” with “Like that lor” to “Busy lor” to “OK la, just tired”. Yet choosing to actively commend ourselves for being tired is a conscious decision, and one which we need to resist.

If it weren’t already obvious, let me make it explicit: approaching tiredness in this fashion is a Very Bad Idea. It wreaks havoc on our mental and physical well-being, not to mention our expectations of what we can be reasonably expected to accomplish in a single day. It wrecks our relationships, self-esteem, and our ability to draw pleasure from the things that truly matter.

And in viewing exhaustion as a measure of how hard-working or fulfilled we are, we mischaracterise rest as a moral failing, rather than a fundamental pillar of physical and mental health. As Dr. Lim points out, “In our culture, we tend to see rest as a waste of time which is, of course, wrong. Our lack of rest is what is fundamentally causing tiredness in us.”

All of this is to say: we need to stop treating tiredness as a barometer of a meaningful life, lest we end up a generation of lunatics.

Waking up feeling wretched doesn’t mean we’re doing it right. It’s a reminder that our bodies need to recharge, and our brains only have so much bandwidth.

Similarly, no matter what Sheryl Sandberg might have us think, believing you can have and do it all doesn’t make you ambitious or empowered. It means you have the self-awareness of a toddler. All our talk of self-care and ‘me time’ means nothing if we can’t accept that to be human is to have limits—ones which we need to respect by allowing ourselves to just lie down for a minute.

So on the off chance that it’s 1:00am and you’re still reading this, put your phone aside. Drink a glass of water, maybe stretch a bit. Switch the lights off. Remind yourself that you’re a human being, and that the next day will seem much less challenging if you can start it refreshed and well-rested.

And, for Pete’s sake, just go to bed already.