All images by the authors.

Lives begin at different starting points. The more financially assured are symbolic of hares — folks with a better head start in life. On the flip side, most average Singaporeans (like the writers of this story) are born tortoises — we hustle steadily and slowly save to get through the much-dreaded #adulting. Depending on one’s circumstances and family history, resources—and in turn, lifestyles—can greatly differ.

In the classic tale of The Tortoise and The Hare, the biggest lesson is about the consequence of complacency. Tortoise, hare, or human, no one comes out on top from getting lulled into sleepy comfort and contentedness.

The same can be said about building capital for retirement and beyond. Stay complacent enough about the amount of savings you have, and everything could be wiped out on a rainy day. That leaves little money for oneself, much less money for the next of kin. In other words, don’t be foolish enough not to plan for the future.

We speak to two grandmothers in divergent circumstances to see how their senior years turned out in the end.

All the Money in the World

Written through the perspective of Ilyas.

The first thing that Madam Saleha asked me after I salam her (that Malay ritual where you kiss the hands of your elders) is if I wanted to order some Thai food on Grab. She insisted on the cash-on-delivery option, wanting to pay for the pineapple fried rice, mango salad, minced beef with basil, and other items that amounted to nearly $80.

Too late. Her granddaughter refused to let the 79-year-old retiree dole out a single cent and had already tapped the order button with the payment charged to her card. It’s a pretty standard scene that plays out among Malay families: the younger kin refusing to let their elders pay when it comes to meals.

“Hehe, thank you!” the septuagenarian eventually relented, settling back into her armchair, holding a wad of $50 notes in her hand—the cash that her granddaughter just gave as a monthly allowance. Filial piety and all that jazz.

Saleha isn’t her real name though; she requested to keep her identity anonymous. What I can tell you is that she and her husband have been together for 60 years. I can tell you that they both live with their daughter, son-in-law, four grandchildren, domestic helper, and a bunch of cats in a capacious HDB apartment in Pasir Ris.

l can also tell you that the cupboard where she stores her baju butterfly is the same place where she has $12,000 in cash squirrelled away. That’s about a thousand times more than what she had in her bank account when she got married at 19 years of age.

“I wanted to climb out of that situation,” she recalled about the days with little to her name, pledging to hustle hard to build a family.

And hustle she did. Like most people in Singapore’s pioneer generation, Mdm Saleha took on a multitude of jobs—any jobs—to sustain her family. While her husband went into education and shipping, she climbed her way into managerial roles in logistics, catering and hospitality.

She forgets how much she earned in those jobs (“So long ago, how to remember!”) but it was substantial enough for her to start investing and buying up multiple properties in Singapore, Malaysia and Jakarta. Honestly, it’s impressive. And they’ve all provided a sweet return on investment, though she hesitates to reveal just how much she racked up.

“I just managed to do it,” she says with more than a twinkle in her eye.

Putting the hows aside, I asked her about the whys. The sparkle in her eye turned watery. All that hustling, all that strategic asset planning—it was always for the kids; their two daughters who grew up in comfortable environments and now have families of their own.

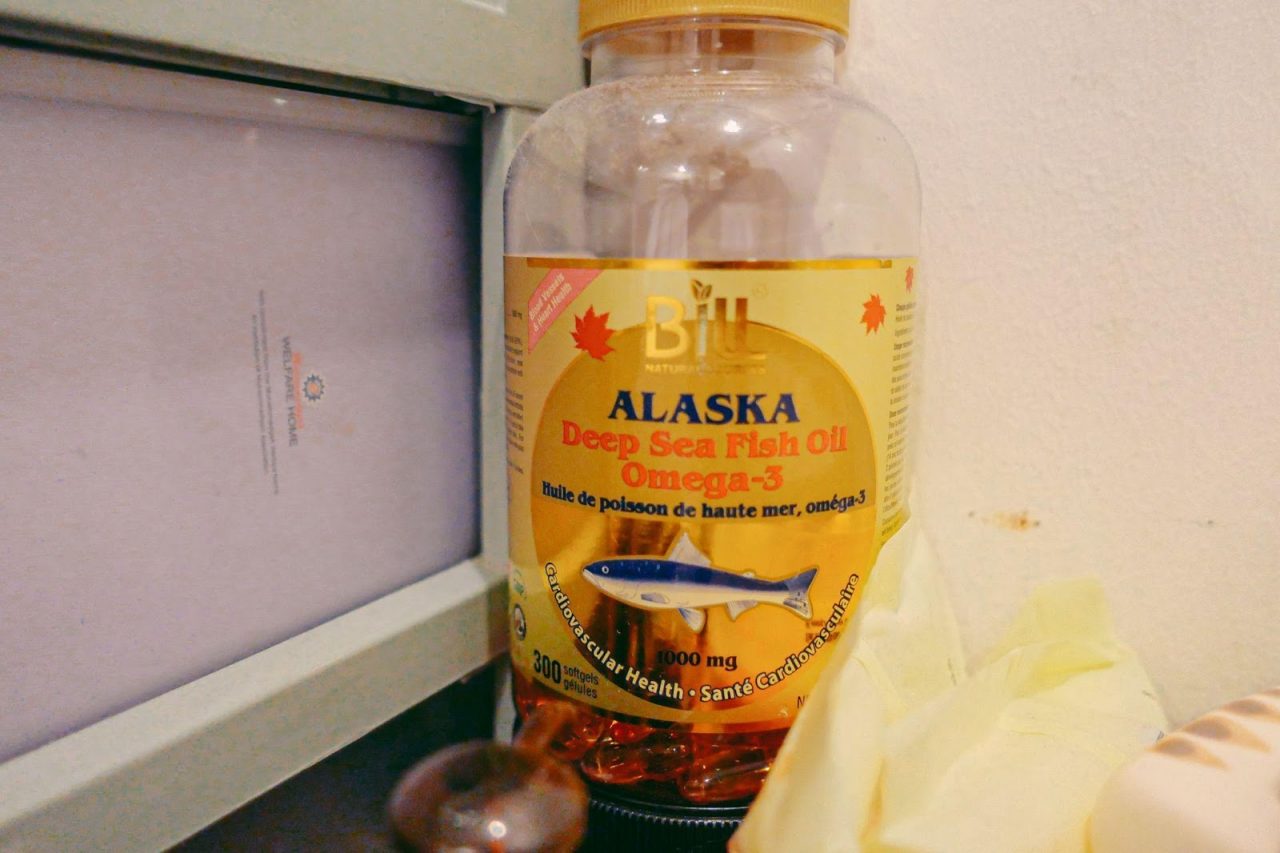

These days though, she has given it all up to live a simple life with her daughter and grandchildren. Surprisingly, as someone with hundreds of thousands of dollars stored in her accounts after cashing in on her investments and properties, Mdm Saleha and her husband live modestly. They share a double bed in a spartan room with a small television. Medication, pills and supplements are tucked away on a small table. Their daily routines revolve around playing with their young grandkids, short walks around the neighbourhood and watching whatever’s on the telly.

There’s a reason behind living frugally — all the wealth that she built could be undone without thoughtful planning or lifestyle adjustments on her end. As we tucked into our desserts, it’s clear that they’ve never fancied the high life. Macaroons, panna cottas and parfaits? Nah, just chendol and some durian for them, thanks.

Perhaps it’s this hardline principle towards prudence that enabled her to accumulate assets so easily. To Mdm Saleha, money is no issue at all. There’s the occasional splurge to go on holidays overseas during The Before Time, but that’s pretty much it. Otherwise, the money stays in her bank account (and her cupboard) to stretch out as long as possible throughout retirement.

As confident as this grandmother was in her savings—she’s got more money to her name than the funds of both her daughters combined, she reckoned—there’s always the danger of having it all obliterated by unexpected financial burdens. Leaving little to pass on to her children and grandchildren.

I have to admit, I struggled to even broach the subject of legacy planning, the financial strategy to bequeath assets and wealth to the next of kin after death. Culturally, it’s just not good etiquette to talk about death—much less post-death affairs—with an elder.

After some poor attempts to dance around the subject, she gets the hint.

“I haven’t really planned anything, to be honest. I trust my daughters to split my assets equally because I raised them to be sensible people,” she affirmed. In the hustle to snowball enough funds for a decent livelihood for the family, the official affairs of her wealth after going beyond the veil had not mattered that much to her.

But it does matter, I brought up. Tailoring exactly how she would like to distribute her assets would at least give her peace of mind about how her kids and grandkids will carry on. If she has the capacity to plan things out, why not?

She laughed it off. For Mdm Saleha, there was never a doubt that her daughters and their families will get along just fine even without her help. Like her, they’ve learned to be fiercely independent women who aren’t dependent on anyone else but themselves.

She does know, however, that her middle-aged kids will end up inheriting a substantial amount that’ll ensure they continue living in comfort for the rest of their lives.

Leaving the HDB flat with a sense of admiration (and more than a tinge of envy) over her nonchalant frame of mind towards wealth and assets, I wonder what the thought process is like for other retirees who aren’t as privileged.

Last in Priority: A Frugal Approach to Modest Living

Written through the perspective of Eve.

Nothing means more to Mdm Sally Chan than her family. At 73, she continues to be a selfless giver.

As I entered her 1-room rental flat, it wasn’t so much the tight quarters that caught my eye. Neither was it the quirky decorations that colour the interiors. Rather, it was the word ‘love’ that marked Mdm Chan’s otherwise plain t-shirt. It is perhaps the most accurate term one can use to describe her.

If I were to track Mdm Chan’s career path, it’d be a long list of odd jobs. There were so many that she could barely recall them all.

Since her twenties, she had worked as a babysitter, packer at the wet market, mixed rice stall helper, chicken rice seller, office cleaner and quality control inspector at a factory.

Some of these were part-time jobs that paid $40 a day; others were monthly gigs that provided a couple of hundreds. The highest was a contract job which offered approximately $1,300 a month.

As a divorcee and single mother raising two young children back then, Mdm Chan exclusively picked jobs that required little travel time. They had to be flexible enough so that she could still keep a watchful eye on her children.

The hustle life plopped her into a busy, recognisable routine: Work hard. Money in, money out.

Despite having little to spare, Mdm Chan made it a point to allocate a portion of her earnings into a bank account. Never mind that those savings got wiped out when her son needed it for school. Never mind that she had to give up her dream of living in a 5-room HDB flat with a balcony.

Having sold her first house after the divorce, Mdm Chan had to live with her daughter for a period of time before moving to her current rental flat.

Her daughter, also a divorcee, was busy earning dough for her family and had little time to care for the kids. Mdm Chan then quit her job, stepping in to care for her grandchildren as a paid caregiver.

Retirement only began at 66, when the family’s financial situation stabilised. Life is a lot less hectic these days. Every day, she wakes up at 7AM to prepare breakfast, before walking to a coffee shop to buy lunch around 12PM. She then cares for her plants, does some housekeeping and watches TV before preparing dinner.

At times, medical ailments like knee joint pains arise. Doctors have made in-house visits, while social workers check in occasionally. There are trips to the grocery store too, but that wraps up her daily routine.

The plan was to stay for dinner. Rather than opting for food delivery options, Mdm Chan insisted on a hearty home cooked meal. We weaved through the tight walkway, chatting as she turned her attention to boiling soup in the kitchen. Through it all, a loud Hokkien tune played on the radio.

Discussions about death may be disconcerting and even morbid for many. When prompted for her thoughts on the topic, she remarked: “Aiyo, What’s so scary about death? We all die one day.”

When people spend their most productive years fulfilling familial responsibilities, this causes them to neglect their own retirement and savings. In wanting to provide for her loved ones, Mdm Chan has left little for herself. She was never a top priority.

While Mdm Chan is content with living a modest life, she sometimes worries about her dependents; and wonders if they’ll get along fine in the future after she passes on.

“I don’t have much to give them, and I’m lucky that they have stable incomes. But worrying has always been part of my nature. Good thing I’m healthy. At least for now, ” she laughs.

Silence descended momentarily, and there seemed to be a collective tenderness between us. Even in the absence of words, I knew that the situation would be vastly different if a serious illness ever came knocking on the door.

Coming from the pioneer generation, she depends on a small allowance from the government and some pocket money from her children. These quickly go into her monthly rent and daily expenses, leaving little to spare for other luxurious wants. She rarely pampers herself with anything — no annual vacations, branded handbags, fancy high tea sessions, or anything of that sort.

As we sat down for dinner, Mdm Chan acknowledged that she’s considered fortunate despite having little left for retirement. In fact, some elderly have it worse. Others may be in a similar financial predicament, but with the added adversity of being sickly and no family members to rely on. With no safety net, retiring comfortably would be the last thing on their minds.

Over the course of my stay, I noticed how one neighbour casually stepped in the house twice — first to collect some leftover red bean soup; second to distribute some rice dumplings. I get the sense that social ties are thicker here than in wealthier, more affluent neighbourhoods — there seemed to be an unspoken, mutual dependence between the old folks.

Retirement planning is akin to winemaking — the process is slow and requires a long term view. The finished product, however, will be well worth the wait. Surely, not every person gets the luxury to plan ahead, like in the case of Mdm Chan. But oftentimes, it is lack of foresight that holds many back from going forth with an official long-term strategy such as legacy planning, like in the case of Mdm Saleha.

7PM arrived in a blink of an eye. It was two hours before her bedtime; a cue for me to head off.

She catches my eye and smiles. A genuine, kind smile.

“To be honest, I don’t have great advice for young people, except that if you have the ability to save or plan ahead, then do that. These are habits that I believe should be imparted from a young age. I tell that to my grandchildren too.”

“If you have $1, spend 70 cents and keep the rest. You’ll be surprised by how these things add up.”

Who doesn’t wish for a comfortable life after slogging for years? With so much to consider (and life getting in the way), planning for retirement and beyond can get overwhelming. But in dreaming about the life we envision, not all of us are actively thinking about ways to make it a reality. Ironically, we could end up being our own villains by holding ourselves back from the life we seek. Take it from the grandparents then: live old, plan young.

This story is published in partnership with AIA Insurance.

If you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.

What’s your dream retirement life like? Share your thoughts with us at community@ricemedia.co