All images RICE file photos save where otherwise stated.

Oh, no. Here we go again.

This week’s announcement about the tightened restrictions made my gut clench in an unpleasantly familiar way. It caps off a week of mounting unease, as the mushrooming TTSH cluster, along with the jump in community cases, triggered dormant-but-not-too-distant memories.

Last Friday, I was getting coffee with a journalist friend when she mentioned that her colleagues were all on edge: a COVID-19 task force press conference had been announced for that evening. Oh no, we joked. At least we got to catch up first.

On Sunday night, my phone pinged with a Slack notification from my editor. Sorry to text at this hour, but given the recent spike in COVID cases, we will WFH for the next two weeks. As the week wore on, my plans dwindled, while my bag filled up with hand sanitiser and wet wipes.

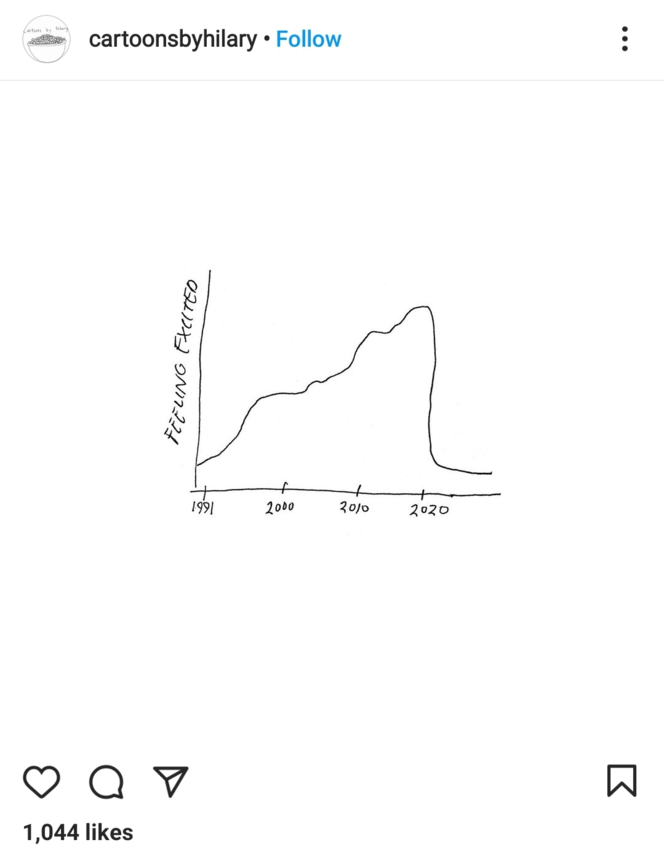

The return to last year’s hair-trigger edginess was all the more dizzying for how quickly it set in. For the last few months, I’ve been catching films at the cinema and going for Pilates without hesitation or fear. While a bump in cases was always a matter of when, not if, things still feel a bit too reminiscent of 2020, and my feelings are all over the place.

Oh no, indeed. It’s blah. It’s restlessness. It’s ennui. It’s not despair, but nowhere close to optimism. It’s the shrug which accompanies any mention of travelling again, the urge to punch anyone who says the words new normal, and the dread of reading the news mixed with relief mixed with guilt for feeling relief, capped off with a minor existential tantrum.

What right do I have to complain when people in India are begging for oxygen on Twitter? Why should any of my first-world problems matter? But hell, aren’t my feelings valid, too?

The only word I can think of for it is sian.

Feelings have been great fodder for content this last year. The pandemic has spawned a whole sub-genre of thinkpieces devoted to unpacking the collective mood, from last year’s viral article from the Harvard Business Review on grief, and more recently, the New York Times’ treatise to languishing.

Most of these, however, have been framed for audiences in the global West, only just coming out of lockdowns on a scale unlike anything we’ve experienced here.

Singapore has had quite a different pandemic ride. The first half of 2020 was a washout: anxious foreboding (February and March), followed by the trauma that was circuit breaker and the crisis in migrants’ dorms.

But since Phase 2 began in mid-June, now almost a year ago, life has been on a slow creep back to normal.

Re-entry anxieties largely subsided by around October. By the end of the year, we were actively impatient to get on with things: for the five-person cap to be lifted, for the vaccination programme to finally begin.

Since the start of 2021, life has continued to settle, but the itch hasn’t really lessened. Things already looked normal in so many ways that this only highlighted where they were not.

In my less generous moments, relief at moving back into the office and the vaccination rollout paled next to growing frustration at everything else: the endless traffic on the roads, the crowds packing every square inch from the rail corridor to Nex, at how SafeEntry adds five minutes to everything. Even moments of comic relief—the Ever Given, lawyers who are not cats—belonged to their own category of ‘only in 2021’, where ridiculousness is directly proportionate to bleakness.

Throughout it all: cabin fever, restlessness, the underlying hum of a pressure cooker on low, bringing us back to where we are now. Not back at square one, but not quite where we’d hoped to be either. Sian.

Generally speaking, sian comes in two flavours: boredom and resignation. Both are laments, but the former tends to be reserved for minor grumbling, while the latter expresses chronic discontent.

The current mood taps into both, but my editor pointed out that pandemic sian has a practical side to it too. There’s an unfortunate time-warp effect in how the day-to-day seems to be getting better, but other things—usually big ones, the milestones—remain frozen in place by the pandemic.

BTO construction gets held up. Overseas opportunities have been reconsidered. Risky career moves are put off. The big yearly holidays we plan our leave around have evaporated.

“In a country where aspiration drives so much of who we are and what we want, it’s particularly sian to feel stuck,” he suggested. Insofar as resignation is about helplessness, and helplessness is about a lack of control, the pandemic has cut right at this—the very Singaporean illusion that anything can be tamed with some bullet-points and a roadmap.

Which is where we come back to the small things. Lacking the big events to latch on to, we’ve shrunk ourselves to fit this shitty year.

I mean this in both good ways and bad. Flouting gathering limits, for example, is really a small way of trying to re-assert control, to make life go back to how it was before. But there’s a more wholesome side to how the mundane feels suddenly massive, too. Where would we be without sustenance from the small joys—dining out with family, cuddling our pets, even the repetitive cafe-hopping circuit—which helped us keep holding out for bigger ones?

Singaporeans are not known for our idealism, but the last year has only proved how much we rely on believing in better days. If we’ve held on and complied so well, for so long, it’s because we knew that while things could be better, they weren’t all that bad, and they could also be much, much worse.

This, for me, is the central irony at play here, and why the cognitive dissonance feels so great: while sian is inherently pessimistic, our current angst is really rooted in hope.

For a nation of supposed cynics, we’re very good at having expectations, and the approximation of normalcy we’ve enjoyed for the last six months has only strengthened this. Order, progress, development (and, dare I say, the instinct to compare ourselves)—the pandemic has only slowed these from the turbo-charged rates we were used to, not killed them off altogether. This is more than can be said for many, both within our borders, but beyond them too.

I don’t want to trivialise the pain of the last year, especially when so much of how it went depends on our subjective circumstances. Personally, I’ve ridden out the year in the same job I started it in, with my loved ones all around me. By any measure, this is obscenely good fortune.

2020 will be remembered differently by so many: by families whose finances went from ‘getting by’ to ‘precarious’ overnight, and those who toppled from precarity into distress. By businesses and industries, small and big alike, many of which haven’t recovered, and plenty which never will.

By our hundreds of thousands of migrant workers, still penned up in their dorms after a year, worrying about their families back home all the while.

In March, young protestors from Myanmar I spoke to told me that the military coup had driven the pandemic to the back of everyone’s minds, even as the healthcare system teetered on collapse. Earlier this week, a colleague described a news clip he’d seen of the nightmare engulfing India, of corpses literally being cremated in the streets.

“Not to sound preachy, but it made me pause,” he said. “It’s not like it made me stop complaining, but it put my complaints in perspective.”

At this stage, I think many of us will have resigned ourselves to 2021 as another lost year, one of start-stops and dreams deferred (again).

It sucks. I can’t pretend it doesn’t. But I can’t pretend that getting to write off 2021 isn’t a privilege, too. That we can choose to roll with things—to say that the worst fallout from this year might just be more lost time and money, not death and devastation and heartbreak—is already so much in itself.

As I struggled through this draft, the question of what we can choose to accept niggled at me. Managed expectations can be liberating, after all (and I say this as someone idealistic enough to try to make a living from writing).

Still can’t go on holiday? Just save that money, I guess, or make up for it with nicer dinners. Can’t do that big group gathering? Stay in and do a small movie night. Can’t make that big career switch just yet? That’s annoying, but maybe that space can be filled with other things: opportunities to work on our relationships, or more breathing room before the hustle resumes. Time, after all, is fluid. (In other words: bo bian, lah.)

And yet, one of the biggest lessons of 2020 was how much the outcomes we live through are shaped by decisions we make, by things we can choose and conditions we refuse to accept.

Already, many of the cries for ambitious structural change from 2020 risk fading away. Gaping inequality, the climate emergency, our shameful treatment of migrant workers and precarious gig-economy labour: all these will continue unless we actually act on the knowledge the pandemic forced us to confront.

Just before the circuit breaker was announced, one of my colleagues wrote that apathy is a luxury we cannot afford. I don’t think this is any less true today.

What we choose to do with our days is what we choose to do with our lives, and to recognise this is to claim power we don’t always remember we have. The danger of feeling sian is not that it exposes the folly of having expectations, but that it dulls us to how much we can still do, even in the strange, fragile space we live in now.

At the start of May, I re-read one of my favourite poems: The trees are coming into leaf, it goes. Their greenness is a kind of grief. Last year is dead, they seem to say. Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

So we’re sian. We’re still stuck and tired and drained. But the trees have stayed green all this while, and when you listen, there is birdsong.

Tell us what you thought of this story at community@ricemedia.co. And if you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.