It’s always better to be safe than sorry—unless being “safe” really means being stupid.

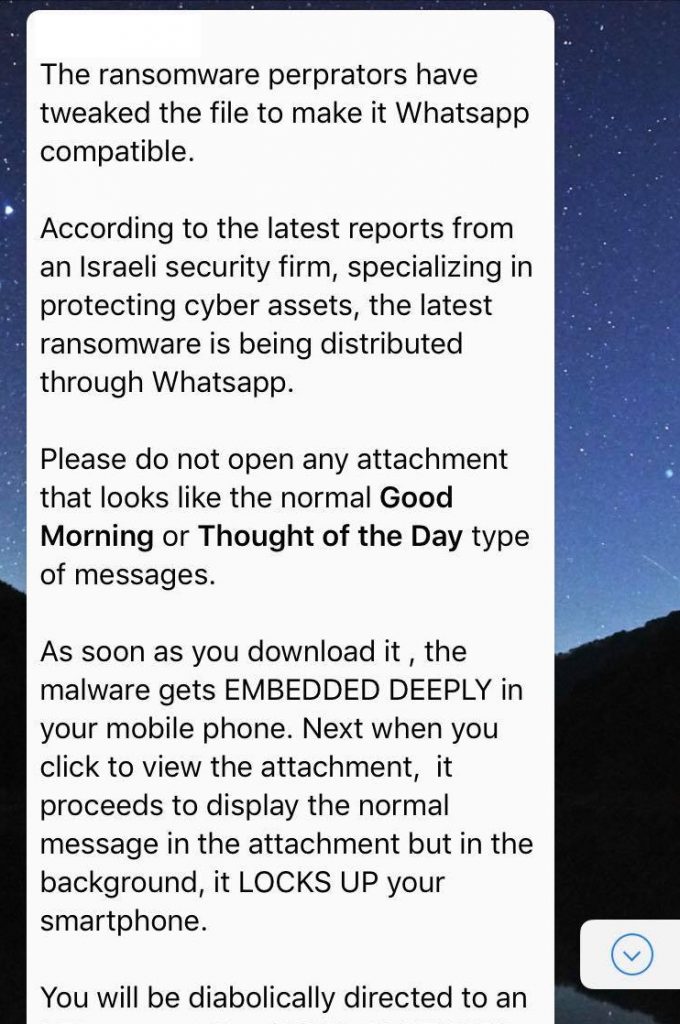

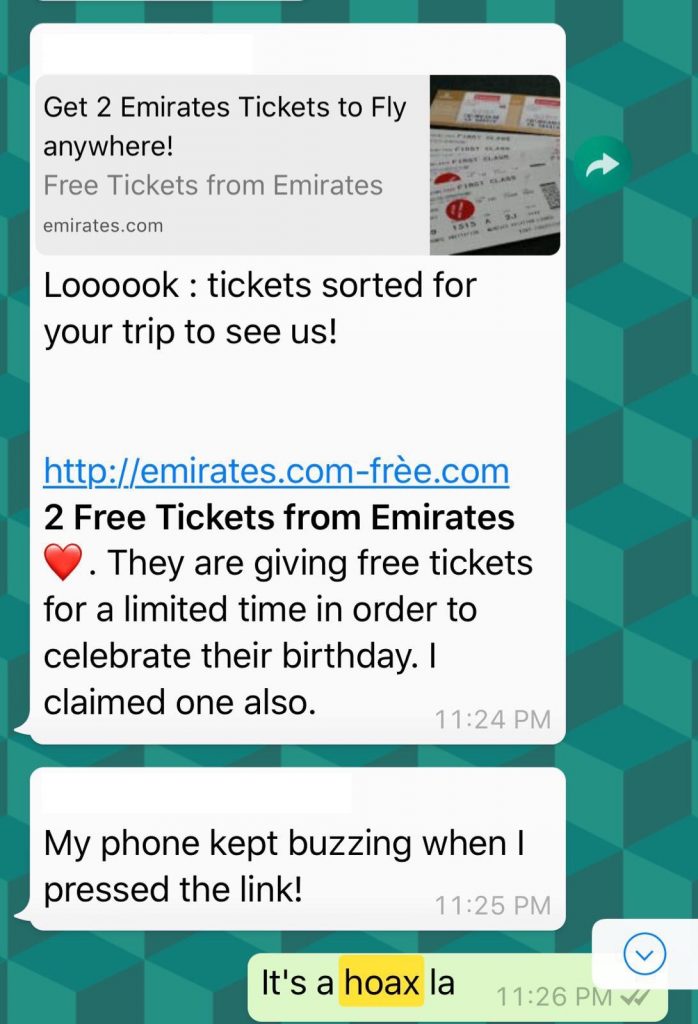

This is what I can’t help thinking whenever I receive another chain message via Whatsapp. For instance, it can be a $100 voucher for Fairprice, which I will have to click on a dubious link to retrieve. There may even be a 2D1N cruise to be won, if only I clicked another link and filled in my NRIC, home address, and credit card number.

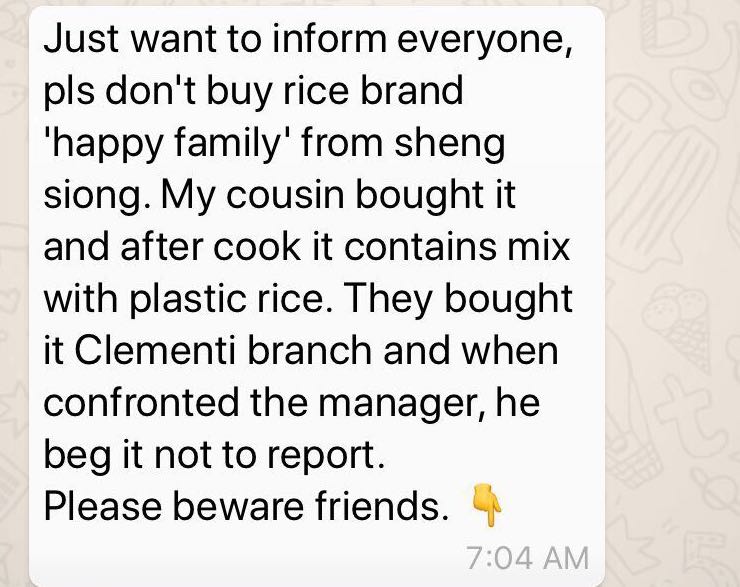

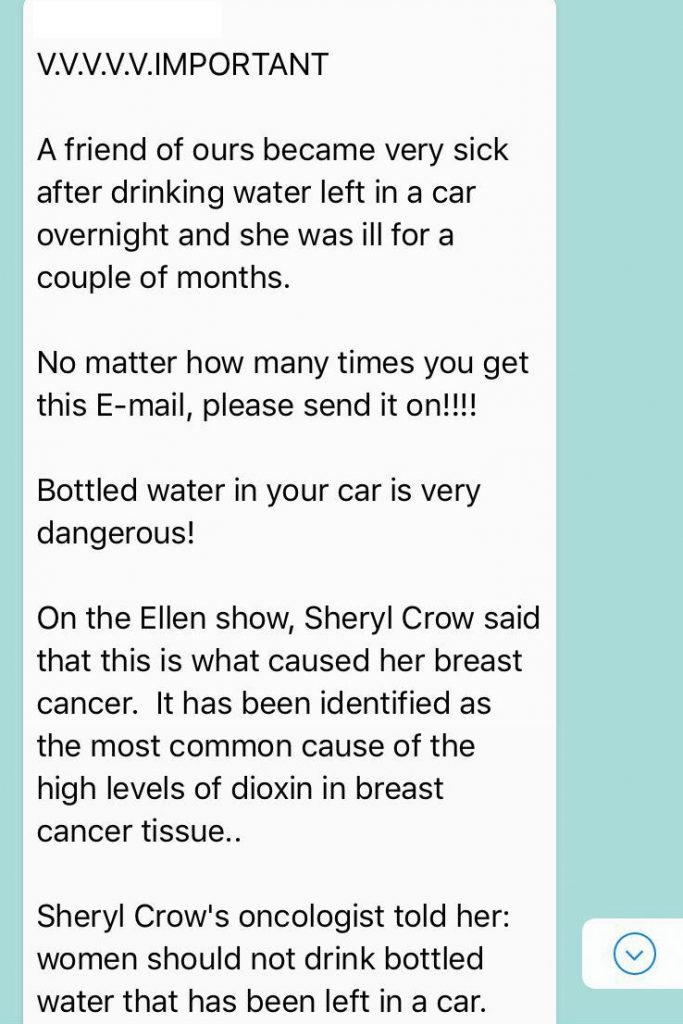

If any of these messages sound familiar, you may also have heard something about “a friend of a friend” of the original sender who drank water left overnight in a car and ended up getting breast cancer.

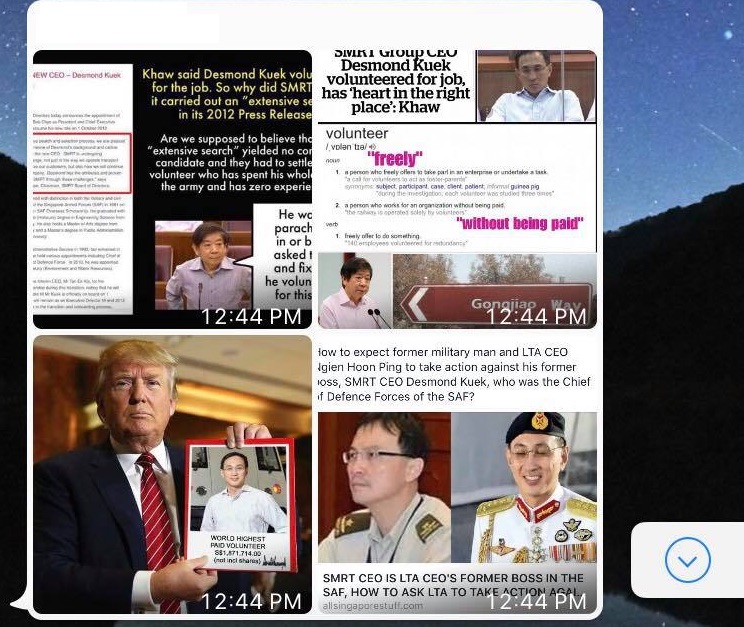

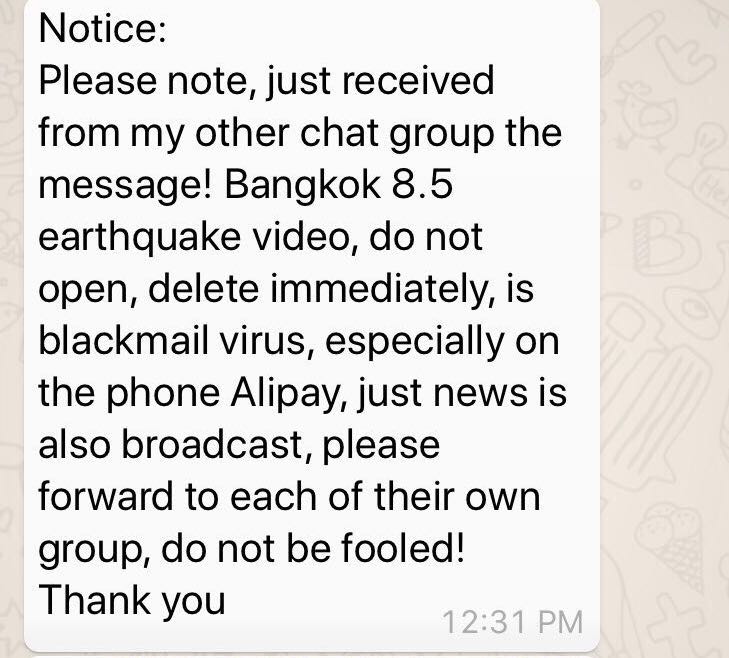

Many of these messages don’t just sound incoherent and completely bonkers, their content is often also sensational and vague. If you’re lucky, they’re kind of grounded in common sense. Otherwise, any semblance of truth tends to be stretched to an extreme.

They also typically offer a warning or reward for the recipient, effectively capitalising on human tendency to be drawn towards emotional extremes such as joy or misery.

Think about it this way: Whatsapp chain messages are the OG fake news. It doesn’t matter that these chain messages aren’t verified, and sometimes even describe completely inaccurate situations. They’re ‘fun’ to read, easy to digest, and so will get shared freely anyway.

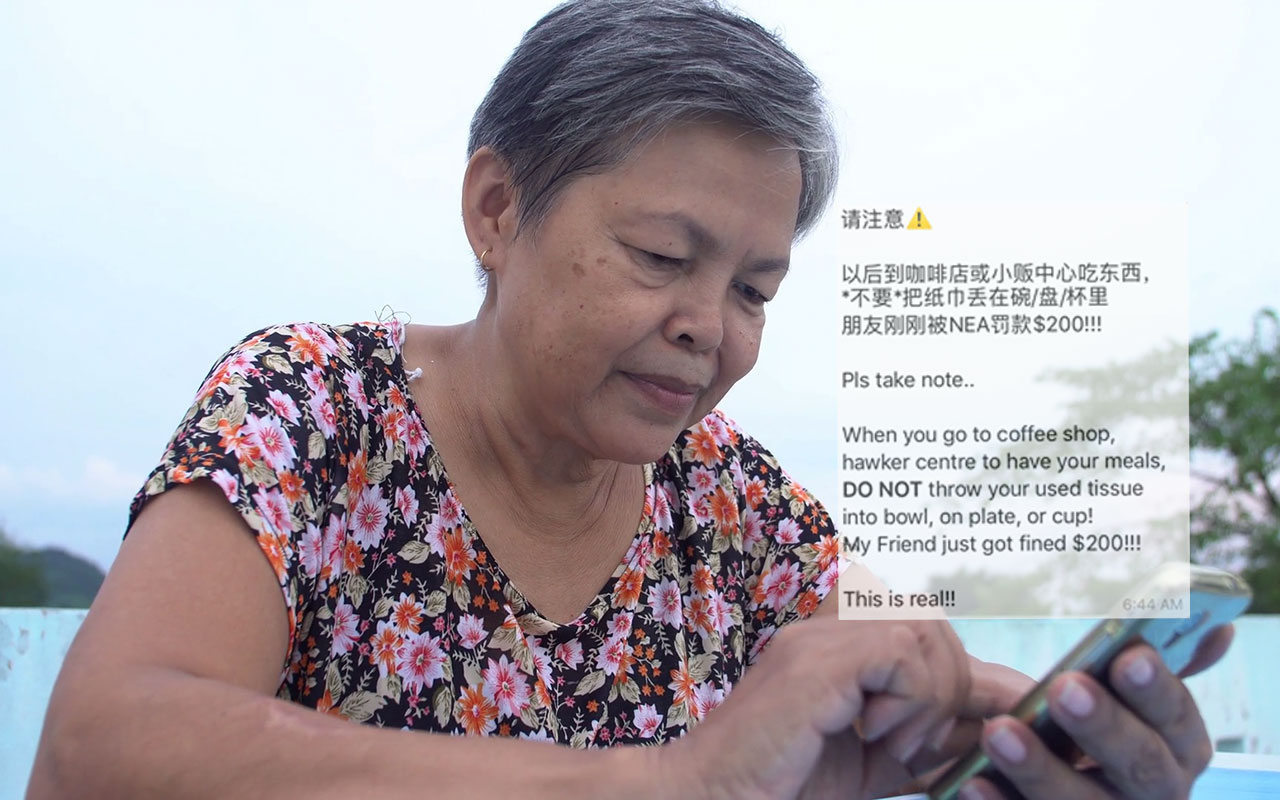

And more often than not, this fake news is proliferated by the older generation, likely in their mid-forties and older.

We understand that they didn’t grow up with this technology, hence they may be unfamiliar with the nuances of usage. This includes recognising basic style indicators that raise red flags, such as bad spelling, unnecessarily bolded words, and capitalised sentences with multiple exclamation points.

Yet despite our insistence that chain messages spread fake news, the elderly tend to be cautious to a fault. Many choose to abandon common sense by reassuring themselves that they can’t possibly lose by ‘playing it safe’.

It doesn’t help that a lot of these messages contain health warnings. Since the elderly are likely to suffer more health problems, news about illnesses and diseases can be slightly more ‘triggering’.

After all, they reason that it’s just a text message. Where’s the harm in forwarding these messages if it can save others from getting cancer or making some disastrous life choice?

Unfortunately, this desire for safety can quickly turn into paranoia. They eventually appear more gullible than careful.

In addition, their naivety isn’t limited to ‘negative’ fake news. Even forwarding ‘positive’ chain messages, such as ones about a chance to win a $50 Starbucks gift card, reinforces their belief that all chain messages are real.

In fact, trying to cure Mean World Syndrome by believing in whatever goodness comes their way may only perpetuate one’s irrational fear of a supposedly scary world.

But perhaps the most dire consequence of blindly believing fake news is not being able to discern what’s real and what isn’t.

In a friend’s family group chat, her mother thought news about the Oxley Road saga was fake and chided the sender for spreading false information. My friend had to clarify that the news was real and had, in fact, just been reported on TV.

Not only do chain messages show how out of touch with reality the sender really is, they’re also obvious lies.

Even though these messages probably aim to warn us, the outcome is the total opposite. Most of us delete the message without even reading it, because we are able to immediately suss out a fake message simply based on its format and how it’s presented.

As another friend shares, “I think out of the 400 chain messages I’ve received in my family group chat, I have read none.”

But perhaps what’s most ironic is that these older people who believe in chain messages are the same ones who once upon a time cautioned us to be wary of strangers online.

One thing remains clear: being smart will always trump being “safe”.