It’s Friday night on Ann Siang Road.

After dark, laughter erupts from tables of office workers with martinis in hand, lounging on the high stools decked along the street of bars aplenty. Past 10:30pm, the boisterous gossiping dwindles like a child sinking deep into slumber, then the hum of late-night traffic takes over.

The corner unit of Ann Siang Road used to be the street’s most notorious troublemaker. On weekends, crowds of gig-goers would spill out of the 1,000 square feet space of White Label Records onto the road. Even after the encore had cadenced, people would gather on the tarmac outside the now-defunct bar and performance venue. They sat, stood, caught a smoke, or chatted with friends—it was a party all night long.

It’s been six months since the lights in the corner unit of Ann Siang Road last flickered on. As dust took the place of where Charlie Lim and Linying once stood, music lovers had least expected their ‘be right back’ in March to be their epilogue. With a heavy heart, White Label Records had ceased operations earlier in June.

“There were so many memories I’ve made there, not just with the events, but with the friends I met there. It was really cool and it was fun while it lasted,” said Daniel Peters, who previously frequented the venue weekly for gigs.

Live music has seen its longest dry spell in history—gigs have been called off, studios have been met with months of silence, and musicians have been left without income for months. The onslaught of Covid-19 not only meant that independent music venues such as White Label Records and Lithe House suffered financial losses from the temporal halting of live events—it also meant that music had to move beyond its physical setting to not be drowned out by the deafening silence.

Having hosted music trivia nights on Tuesdays during White Label Records’ heyday, Daniel, too, had borne the brunt of the cancelation of live events. “I feel that the nightlife and live music industry still have not been taken care of by the government because right now, a lot of them are struggling, a lot of them have closed down, [and] a lot of them are turning to other jobs in order to make ends meet,” he said.

As unfortunate as the closure of the venue was for co-founder Darren Tan, he shared that he honestly ‘kind of saw it coming’. Despite government relief measures provided, rental took a toll on their operating costs.

“Since the beginning of the year, I was already in heavy discussion with my team that it was going to be an eventuality that we might not be able to operate. Rents at Ann Siang aren’t cheap, even with subsidy, it wouldn’t be viable for us to continue there,” said Darren.

White Label Records was co-founded by Darren and his business partner Kurt Loy back in 2018. From Tuesdays to Saturdays, each night was a blast to the past—beneath the soft violet glow, genres such as Asian Boogie, Jazz, Britpop, and 80s Hip-hop came to life as the DJs spun the vintage records on turntables.

However, White Label Records’ spirit of creating a social space for music lovers to appreciate vinyl has not waned. September marked the re-launch of SG Community Radio (SGCR) as a multimedia platform that not only showcases livestream gigs, but also one that spotlights the realms of film and literature.

Led by Darren, the SGCR team includes managing editor Daniel and producer Tan Hwee En. Through getting local creatives on board, SGCR has built up a multidisciplinary repertoire, including podcasts featuring NSFTV, Asian Film Archive, and The Moon. White Label Records’ resident DJs were not missed—their sets have also resumed as weekly livestream shows on SGCR’s Twitch platform.

“With Covid, one thing I’ve learned is that the only people we have is each other. And the only way we can really get through this is to help out,” said Daniel.

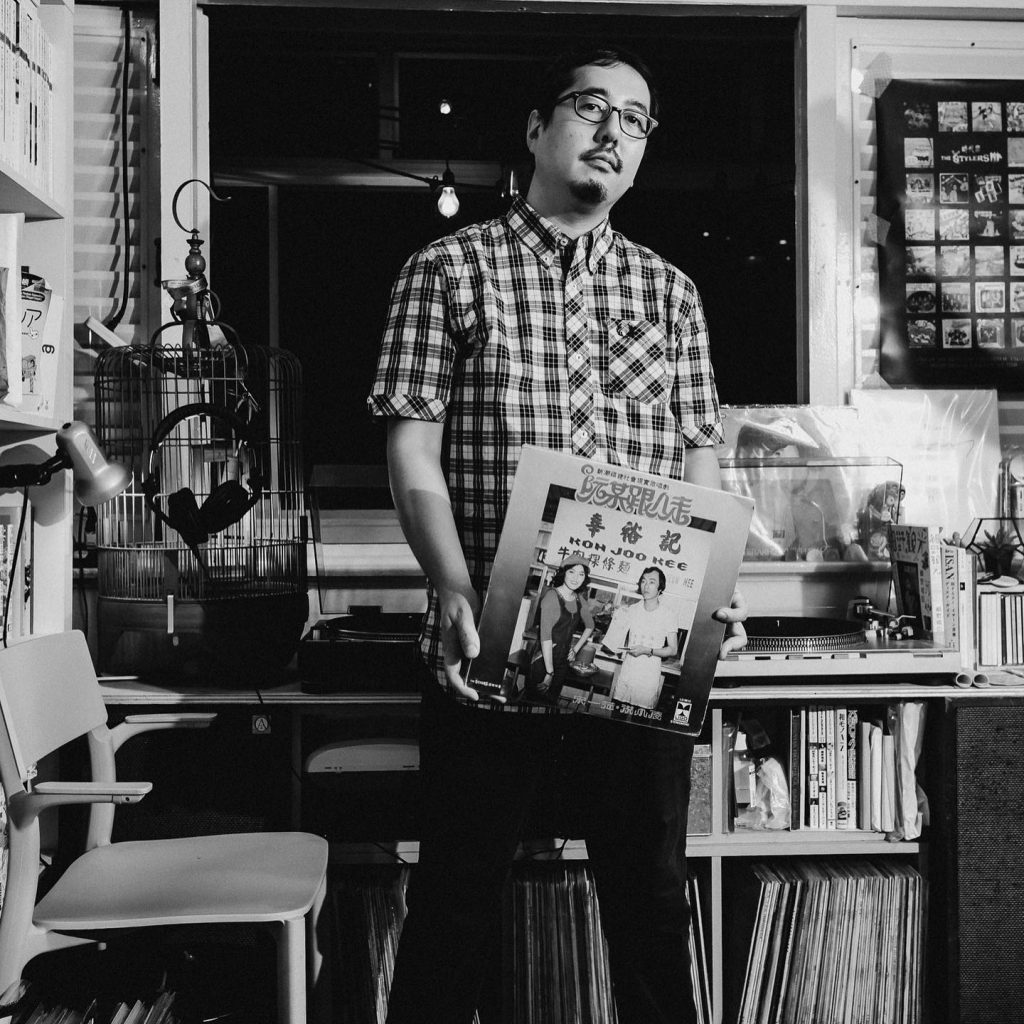

The refreshed concept of SGCR has allowed for Ichiro Nagasawa, better known as DJ Itch, to continue his Saturday NIGHTCAP shows digitally. The ex-resident DJ of White Label Records shared that he was fortunate to be able to celebrate the first anniversary of NIGHTCAP in February before the venue’s closure but bringing Asian Boogie and Japanese City-pop to his fans online is a meaningful experience for him as well.

“The SGCR team has been very supportive to continue NIGHTCAP online and help bring back the audiences. Also, what motivates me about livestream DJ-ing is when listeners share their comments on the chatroom. Sometimes, I would receive good feedback about my music selection,” said DJ Itch.

In the downtime during Singapore’s circuit breaker, DJ Itch revisited his collection of over 1,000 vintage Asian records, which boasts grooves as diverse as the Malaysian pop yeh yeh and the Cantonese Cha Cha. Prior to NIGHTCAP shows, DJ Itch had piloted hour-long sets entitled Stay Home Singapura on his personal Instagram account, and the series has been going strong since June.

“Digging vinyl records from my shelves was an interesting way to find music which I haven’t played in venues before, so I started the livestream to share [this] newfound music with my friends and followers to bring some positive vibes,” he said.

While DJ Itch was able to find a silver lining in the pandemic, the frontman-bassist of local emo band Forests, Darell Laser, admitted that creating music from April to June was a struggle due to the temporary closure of their studio at Lithe House.

“We couldn’t practice as a band and that’s how we usually would write songs,” said Darell. “I miss the energy of playing a live show filled with humans. Livestream just hits different.”

The decade-old performance and rehearsal studio along Madras Street was founded by Anvea Chieu and serves as a gig space for both local and international bands. It hosted bands like Leavings & Requin from Australia as well as Sans Visage and Falls from Japan (when they stopped over at Lithe House on their Asia tours).

Similar to White Label Records, Lithe House’s earnings were punctured by the temporary closure of the venue since the end of March. With utility and rental bills piling up during the circuit breaker, Anvea immediately checked their reserves and brainstormed ways to sustain their business. In June, she took a leap of faith and announced a fundraiser for Lithe House, reaching out to music enthusiasts, local musicians, and regular studio users for donations to help them tide through the turbulent period.

Within the first 14 hours of the launch, Lithe House surpassed their initial goal of $9,000 and raised $14,556 in five days with the help of 385 backers. The funds raised had allowed for Lithe House to reopen its doors for studio booking since 19 June.

In response to the overwhelming success of the campaign, Anvea said: “We believed many would come forward, knowing our contribution to the music scene for the past 10 years. Hence, we were confident [that] we would garner support from a few, but it turned out to be much more than we expected.”

As the pandemic is gradually easing in Singapore, skies are also clearing up for the nightlife entertainment scene in Singapore. Some bars, pubs, karaoke lounges, and clubs are set to resume operations in limited capacity, as announced under a pilot by the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI) and the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) on 6 November. Beginning as early as next month, the revival of nightlife in Singapore hopefully put an end to the curse that had fallen upon nightlife establishments since March.

With larger venues such as The Esplanade, Marina Bay Sands, Capitol Theatre, and more being able to hold smaller performances with social distancing measures in place since 1 November, there is glimmer of hope for live music performances to return in their full glory possibly after Singapore finds its footing in Phase 3.

However, both Anvea and Darren shared that given spatial constraints, performances at local independent gig venues are unlikely to resume anytime soon.

“Rehearsals and recordings are now up and running but live performances may never return at Lithe House,” said Anvea. “These days, no one hangs out casually at Lithe House unless they are there for official businesses.”

In a period of time where live music is taking a backseat, the new normal has seen musicians jumping at any opportunity to play livestream shows in a bid to stay connected to their fans.

Homegrown DJ Robin Chua, who goes by the moniker KiDG, used to frequent both White Label Records and Lithe House regularly for gigs and rehearsals. However, hosting livestream sets on Twitch has become his coping mechanism since the pandemic.

“Live music is important. It uplifts moods and does something good for our mental state. Despite many artists doing shows digitally at the moment, I can safely say that for live music, the best experience is still watching it before your eyes,” said Robin.

While livestream sets have rejuvenated the local independent music scene in trying times, the shared connection between the performer and the audience from being physically present at a gig still remains sorely missed by both musicians and audiences alike.

“Sometimes, even that (livestreaming) can get pretty draining but there’s really no choice now. Like what they say, it’s the new normal and that’s something we all have to live with it until the day Covid-19 subsides,” he said.

Till the faithful day when live music can erupt in song again, the independent music scene will play by ear, without fear.