Recently, my colleague Edoardo wrote an excellent profile on local influencer Wendy Cheng (aka Xiaxue) which, judging from the comments sections, has sharply divided online opinion.

This backlash didn’t come as a surprise. Before deciding to pursue the interview, there was heated debate among the Editorial staff about whether the subject was worth covering, and its relevance to our readership.

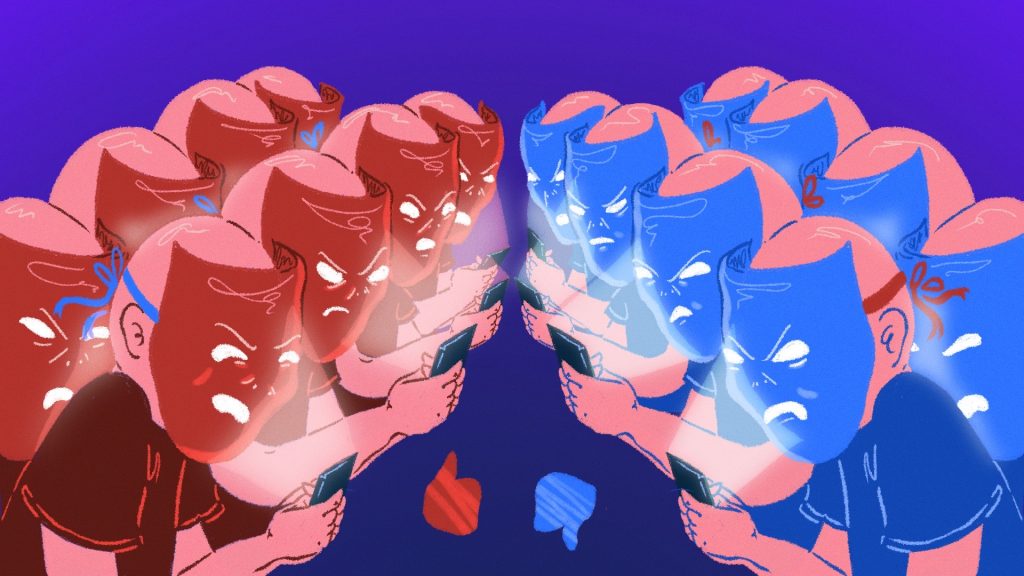

While I personally have zero interest in influencer drama, I don’t believe that the profile vindicates Xiaxue or justifies the things she said. Coverage does not equal endorsement, although in the increasingly polarised world of social media and online discourse, that line has blurred significantly.

In this climate, tackling subjects that fall outside the norms of online echo chambers is seen as an act of betrayal, amplifying problematic voices that need not be heard.

This attitude in itself is problematic. It promotes a self-righteous form of censorship and handicaps our ability to understand people whose views we disagree with. However ‘deplorable’ some of those views may be, we can only address a problem if we make the effort to identify it correctly.

If RICE’s feature of Xiaxue has managed to ‘soften’ or ‘humanise’ her at all, that’s only because the image that had been vilified online was a cardboard caricature, not a human being with flaws and contradictions.

But the problem of mob mentality is not just limited to influencers or getting cancelled by K-pop stans. For every example of public figures getting attacked, there are countless other victims of the online mob that go nameless.

Losing Yourself to the Mob

To better understand how mobs form and mob psychology, I turned to Dr. Geraldine Tan, Director and Principal Registered Psychologist at The Therapy Room (TTR), a local centre that provides therapeutic services for adults and children with depression, anxiety, autism, and other mental illnesses. Dr. Tan has over two decades of clinical experience working with individuals with a multitude of psychological problems, using treatment techniques such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT).

“Human beings have always had this tendency to follow the herd. In the past, it was essential to our survival,” explains Dr. Tan. “To join a herd, we only need a small nudge in that direction. Once the group grows large enough to support each other and reinforce each other’s beliefs, this becomes further assurance that what [the herd] is doing is normal and ‘the right thing to do.’ Anyone who opposes this becomes the minority, and is thus, discounted.”

This is an example of social proof, a psychological phenomenon where people act in accordance with others in an attempt to reflect the ‘correct behaviour’.

“Those that partake in the mob start to lose themselves. More often than not, when asked, they can’t really articulate why they did something except that “it felt right,” says Dr. Tan. “An angry or negative emotion has clouded their judgment.”

The takeaway here is that all mobs feel like they’re fighting for a worthy and just cause. As a result, the individual identity, with its ability to see nuance and uncertainty, gets subsumed into the larger group identity.

This natural human tendency only gets amplified on social media. The online herd is faceless. A person can hide behind an avatar or a screen name without fear that they’ll be held accountable for their behaviour. While anonymity offers individuals safety, there are also no penalties for misconduct, increasing the chance that such behaviours will be encouraged.

“Once we rally around “like-minded” individuals in a herd, we start to feed off each other’s belief that our behaviour is for a righteous cause,” says Dr. Tan. “This, in turn, firms up the group’s conviction to perpetuate that behaviour.”

The Consequences of Feeding the Mob

It’s easy to dismiss local influencers who become targets of the mob because their comeuppance is seen as ‘par for the course.’ Singaporean’s perception of their power and influence justifies the schadenfreude we feel when we see them fall.

But mob psychology doesn’t just apply to influencers and those in power. It can also happen on a smaller scale, against targets who are powerless, ones with no PR teams or platforms to fight against these attacks.

Dr. Tan recounts a case that affected one youth:

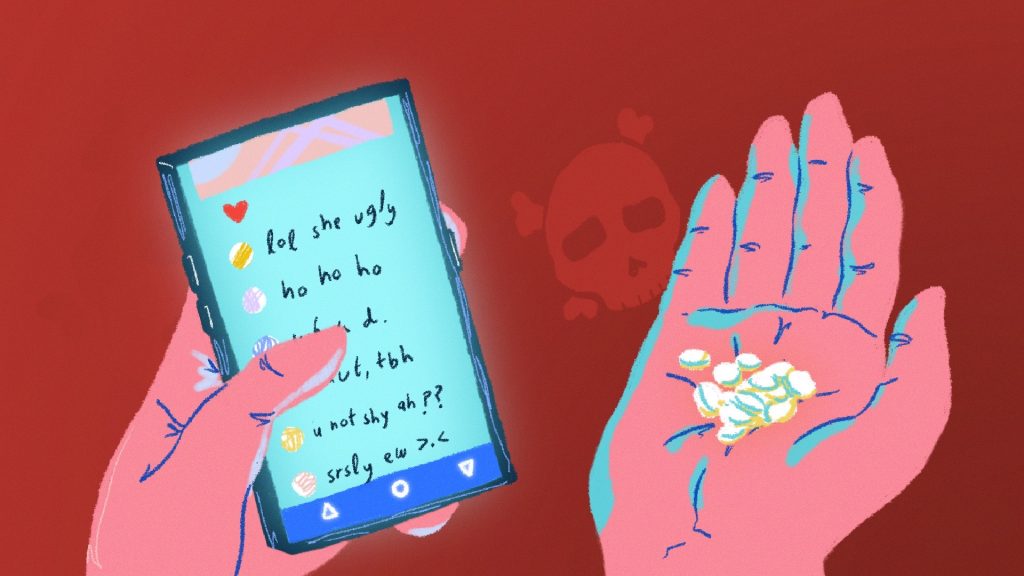

A young girl, N, had just entered secondary school. Like any teenager, she develops a crush on a male schoolmate.

When her crush shows N more attention than the other girls, K, her classmate, becomes jealous. She creates a “spam account” on Instagram, and invites all of her schoolmates, including N’s friends, to follow the account. In the beginning, K’s posts are only mildly critical of N, as she tries to recruit people to her ‘cause.’ The classmates reinforce her negative behaviour by following the account and liking the posts.

K has now planted the seed. Support for her cause, in the form of follows and ‘likes’, empowers her to escalate the attacks, as she grows more abusive.

Eventually, N finds out about the account. The sudden attack leaves her vulnerable. The fact that K has so many followers, including people N thought were her friends, is devastating.

The breaking point came when her crush decided to “join in” by following the account and ‘liking’ the posts that criticised her.

Feeling isolated from the rest of her classmates, and unable to cope with the constant attacks, N tries to commit suicide by taking an overdose of pills. Thankfully, she is found by her sister in time to seek treatment and therapy.

For every story about public figures getting taken down by the mob (rightly or wrongly), there are stories like N’s that we never hear about. These stories are more prevalent, yet invisible. While the motivations behind every mob may be different, the fundamental psychology of how mobs work remain the same.

A RICE Guide to Being More Human Online

To combat the negative effects of the mob, RICE has come up with three rules for a kinder internet:

Rule #1: Communicate as you would if the person was sitting across from you

Call it the 21st century update to the Golden Rule: do unto others as you would have them do unto you—offline. This bridges the gap between what’s acceptable conduct in-person versus what’s acceptable on social media.

Rule #2: Engage – but be specific and constructive in your feedback

Creating a kinder internet does not mean ignoring problematic statements. It’s about addressing the point(s) being made rather than the person making it. For example, instead of dismissing someone as ‘just another alt-right/left wing/PAP/Opposition’ supporter, be specific when you disagree, avoid invoking a straw man or jargon, all while remembering rule number one.

Rule #3: Avoid reacting based on negative emotions

This includes seemingly innocuous behaviour such as liking or retweeting a negative post online, which empowers the perpetrator, while absolving them of responsibility.

These rules are by no means exhaustive, but it’s a start towards tackling the more toxic aspects of social media.

As Dr. Tan states, it takes a conscious effort to transcend our most primitive impulses. To combat the effects of the mob, we have to want to be thinking and feeling individuals first.

Will this call for moderation actually work? Well, the response to this article should give us an early sign of how much room there is to improve.

It all depends on whether we actually want to promote constructive dialogue, or just live in a world of battlelines, where we can all hide behind the illusive safety of ‘being right.’