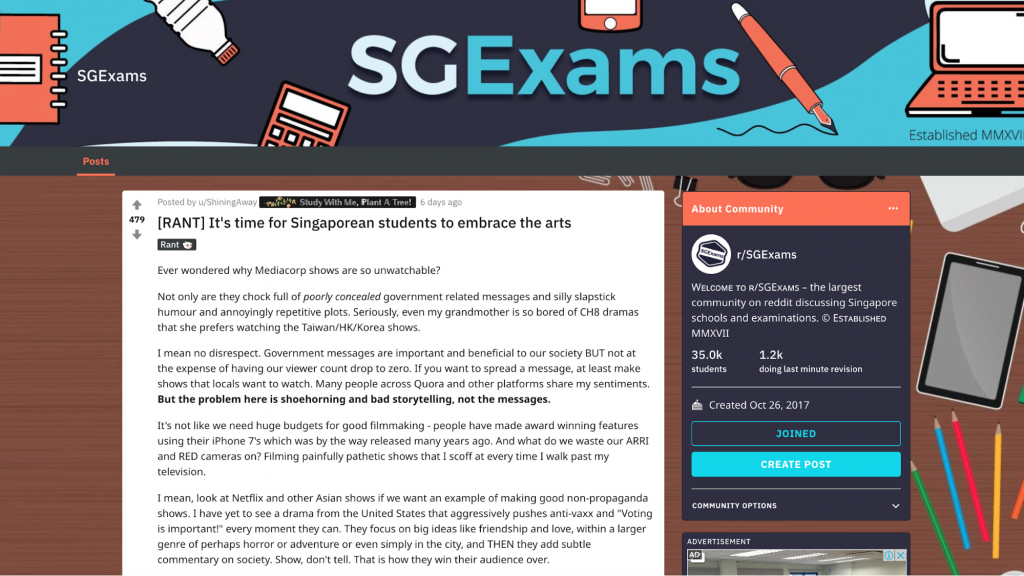

From Singapore Airlines to BreadTalk, Charles & Keith to OSIM, there are many locally-grown brands that Singaporeans take pride in. Our public broadcasting conglomerate, Mediacorp, is not one of them—as the posts that pop up every once in a while on r/singapore attest to.

If not for the extension of the circuit breaker and the untimely expiry of my Netflix 30-day free trial, I—a card-carrying member of this Mediacorp-hating demographic—might never have given Channel 8 a second glance. But bored at home with few alternatives for entertainment, I decided to take a nostalgia trip by rewatching some of my childhood favourites: The Little Nyonya (2009), Daddy at Home (2009), Love Thy Neighbour (2011), and It Takes Two (2012).

It doesn’t feel like so long ago that I was Channel 8’s most ardent fan. At first, my parents encouraged this, hoping it would improve my command of Mandarin and translate to better P1 Chinese grades. Later, they even capitalised on it by bribing seven-year-old me with permission to catch the latest episodes if I finished my homework by 9 PM. At the time, I was not the anomaly amidst a sea of Mediacorp-hating peers. There would be entire recess discussions among my P4-5 classmates devoted to psychoanalysing the con-artist characters of Game Plan (2012). Even in secondary school, when most had ditched Game Plan for HBO’s Game of Thrones, there would still be that one or two classmates excitedly discussing the events of the latest episode of 118 or its (less popular) sequel, 118 II.

But nowadays, Mediacorp dramas draw decidedly less excitement from this same generation.

DISILLUSIONED WITH MEDIACORP

“The acting and storylines are subpar compared to the Netflix and K-drama shows,” Chloe Toh, 18, says frankly. The last time she watched a Mediacorp drama was in P6.

“It’s ok, and that’s it. It’s literally only ok,” comments Rachel, 19.

“My issues are that it’s very predictable and bland. They don’t seem to be willing to take risks with their content and explore fresh new stories. I think in general, it’s not very well written either. Plotlines seem either very basic or overly convoluted. […] And it doesn’t help that the dialogue tends to sound quite stilted and isn’t delivered the best, so it becomes even more unbelievable.”

“It sounds so pretentious because literally no one speaks like that in real life in Singapore,” adds Charisse Kwong, 18.

“We pepper our real-life dialogues with fillers. I feel like the screenwriters write as if everyone plans out essays in their minds before they even open their mouths.”

This point about dialogues was something I had picked up myself while on my Channel 8 nostalgia trip.

Mediacorp channels are subject to the IMDA’s Managed Linear Services Content Code, which requires that “programmes should maintain high standards of language and speech in the four official languages of Singapore”.

In more concrete terms, only Standard English (“grammatically correct”) or Local English (“grammatically correct but pronounced with a Singaporean accent and which may include local terms and expressions”) can be used for English programmes like dramas, comedies and variety shows.

On the other hand, Singlish—described by the Code as “ungrammatical local English”, which “includes dialect terms and sentence structures based on dialect”—is allowed only in the case of interviews where the interviewee speaks only Singlish. However, the interviewer himself should not use Singlish.

Given that the vast majority of Singaporeans tend to communicate with their friends and family using the aforementioned “ungrammatical local English which includes dialect terms and sentence structures based on dialect”, it’s really not that hard to see why it might seem unnatural or even pretentious to local viewers when Channel 5’s police officers speak Queen’s English.

“Many Singaporeans use Singlish in their daily conversations, but this aspect is not accurately reflected in [Channel 5] Mediacorp dramas,” says Afeef, 16, who feels that this is less of a problem for Suria.

“Shows on Suria incorporate the mixture of English/Malay conversations that many Malay people are used to.”

As for Channel 8, the Content Code specifies that sub-standard Mandarin—characterised by poor syntax or use of vocabulary, or poor pronunciation—should not be used for locally-produced Chinese programmes. Dialects are also not allowed, with small exceptions such as for terms like ‘ang ku kueh’ and ‘kopi gao’, where the Mandarin equivalents might not be commonly understood. This emphasis on pure Mandarin has led to a similar feeling of surreality for Channel 8 viewers, for example, when superglue is referred to as ‘wan neng jiao’ or a component as ‘ling jian’ instead of using the English word, when even most Chinese-speaking households would probably refer to it as such.

Another effect of this strict language policy is that Channel 8 actors may sometimes “sound unintelligible” as Mandarin is not the first language for many of them, as admitted by Mediacorp script supervisor and scriptwriter Lau Ching Poon in this 2014 interview.

Unnatural dialogue aside, other common grouses included a lack of original plots, cheesy humour, and the same old faces headlining drama after drama.

Admittedly, the last one can’t be helped, due to the creation of non-traditional celebrity status career pathways like ‘social media influencers’ and ‘YouTubers’ that compete with Mediacorp for the same limited pool of local actors. Even then, local actors would also rather venture into larger overseas markets. Malaysian-Singaporean actor Lawrence Wong of Story of Yanxi Palace fame claimed that he made more from one show in China than a local actor makes in two years.

“I think it’s more relevant to Singaporean life compared to overseas TV shows, but it’s quite draggy and the jokes they use are quite lame,” said my friend Yvonne (not her real name), 18.

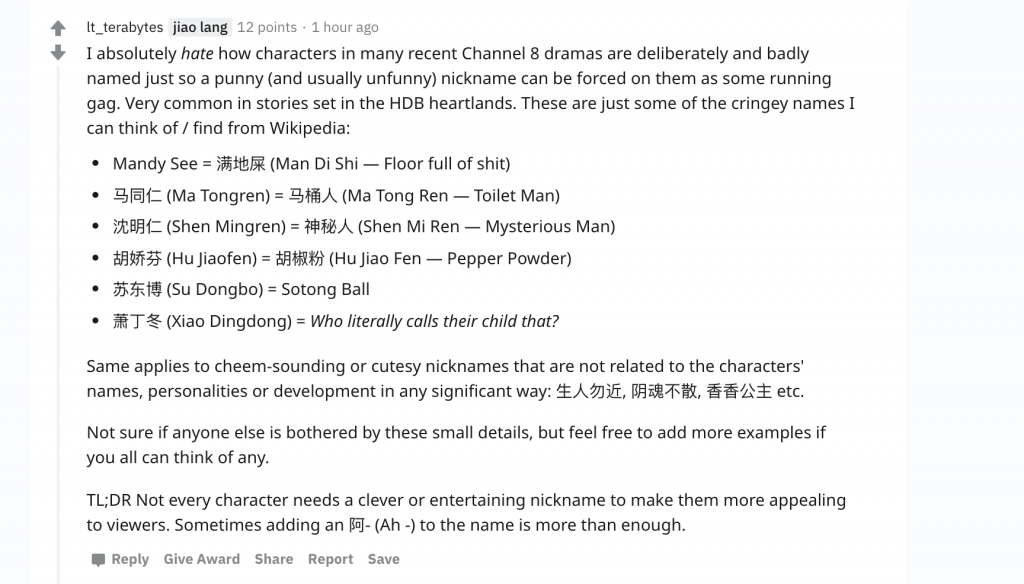

From my own experience, Mediacorp humour tends to rely heavily on pun-based wordplay, visual gags, or Singaporean references. A prime example of Mediacorp humour would be this line, delivered during a breakup scene in My Guardian Angels, which was (at the time of this article’s writing) Channel 8’s most recent 9 PM drama: “You think you’re a dreamboat? You’re just a broken sampan!”

Not exceptionally witty, but hey, somewhat funny and somewhat relatable.

For another friend, Manoj (not his real name), 18, the buck doesn’t stop with dramas: “Our local game shows are also notoriously short and usually copy the format of a well-liked international show rather than coming up with something original, so no one really gets involved. And it’s always the same few people acting as hosts or panelists, making it really boring.”

Considering all these factors, it does appear that local viewers have become thoroughly disillusioned with Mediacorp’s programmes. And yet, there is evidence to suggest that some still enjoy them.

LOCAL TV HAS ITS FANS

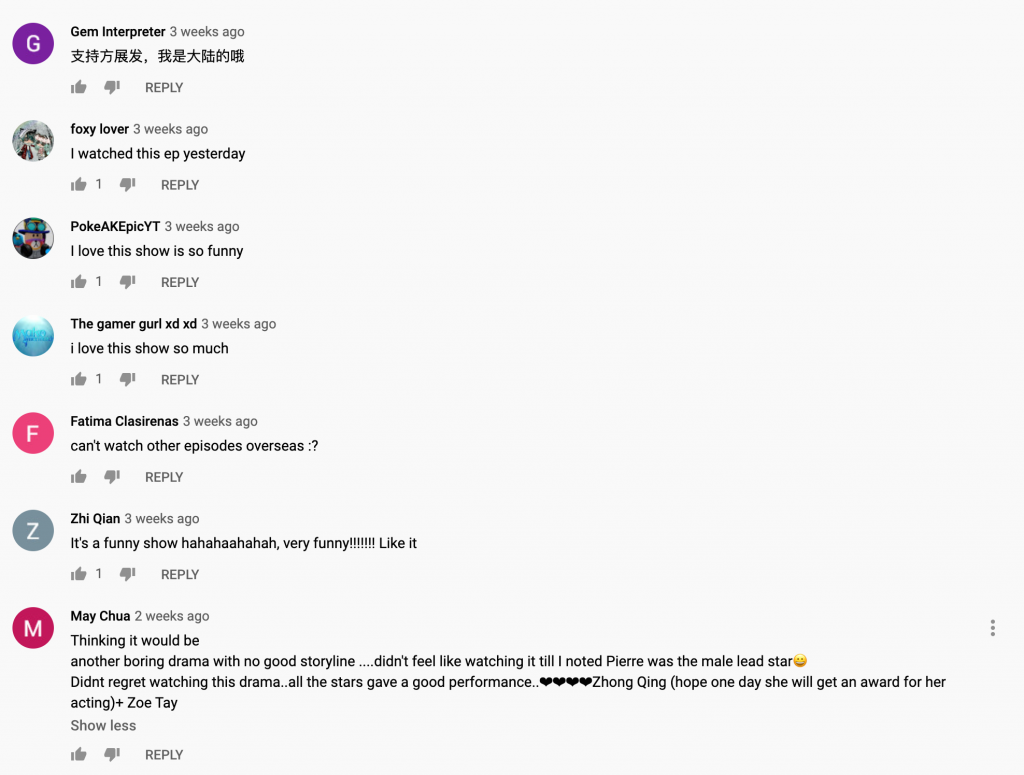

Call it self-selection bias, internet trolls or whatever else you want, but the comments section on Channel 8’s YouTube upload of episode 1 of My Guardian Angels seems to paint a very different picture of Mediacorp drama viewership.

I even managed to locate a teenage fan of My Guardian Angels from within my own social circle: 17-year-old Nicole Lim Regin, who counts Channel 8’s My One In A Million (2019) and the Toggle, I mean, meWatch original Bluetick (2018) among her favourites.

“I love Mediacorp dramas,” she tells me, although she acknowledges that she is somewhat of a minority among our age group.

“My friends always ask me [what I like about Mediacorp dramas] too, and I think it’s the nostalgia that it brings, back to childhood and the family bonding time that comes out of sitting on the sofa together at 9 PM sharp.”

However, Nicole admits that there is still room for improvement: “I think they should definitely invest in [grooming] newer actors for their dramas because newer actors have potential for more growth. Now, it’s just the usual ah jies, so this won’t attract people our age.”

Kenneth Poh, 17, acknowledges that predictability is another issue which plagues Mediacorp dramas: “The cliches of a single mother struggling with work and her child, or an entitled housewife who is deserted financially when her wealthy husband leaves her seem to appear often in Mediacorp dramas, and in the same shape and form.”

However, he adds that predictability is not necessarily a bad thing: “I think there is some feeling of certainty when you are watching the show too, where you can guess how things will pan out. When they do, it is comforting, and in some cases, humorous.”

In fact, one could make the case that Mediacorp dramas are intentionally playing to their strengths by being predictable. After all, it is precisely this predictability which Mediacorp’s most loyal and reliable demographic craves.

“Younger generations definitely find it boring and cliche-filled, but it’s quite the lifesaver for my grandparents, who would otherwise not have anything to do other than read the papers,” said Sia Xinyu, 17.

Elderly people are unlikely to have the technological literacy to go online to watch shows, so free-to-air TV channels like Channel 8 are often the only means of entertainment available to them. Elderly people are likely to take comfort in these stories, which utilise familiar tropes and maxims such as the importance of family.

This theory actually starts to make even more sense when you consider that the ubiquitous community messages about government schemes could actually serve a very practical purpose:

That scene where a group of elderly people sits around a hawker centre table to extol the virtues of CHAS while chowing down on char kway teow? It’s there for Uncle Tan, 76, who is suffering from a toothache but is too worried about the cost of seeking treatment to visit his local polyclinic. That scene where a 40-year-old woman finds out about a Zumba classmate who contracted breast cancer but discovered it early enough to seek treatment? It’s there for Auntie June, 55, an avid watcher of Channel 8’s 9 PM drama, who might not have considered going for a health screening otherwise.

Further supporting this theory is the fact that many of Channel 8’s most recent dramas have featured middle-aged protagonists who face midlife woes such as the loss of a spouse, career woes, and their teenage children.

Who’s to say that Mediacorp hasn’t already abandoned younger viewers in favour of doubling down to appeal to older ones? This could actually be a sound business strategy. After all, by trying to produce dramas that cater to everyone, you essentially end up catering to no one.

But apart from the elderly, another group that enjoys Mediacorp dramas is—surprisingly—the very young. It was my uncle who informed me that my younger cousins, aged 7 and 9, are big fans of My Guardian Angels, and that “They love the 9 pm show.”

This made me wonder when it was that I stopped thinking of Mediacorp dramas as something to talk about with friends, and began perceiving them as “uncool”, “cliche”, and “too cheesy”.

Rachel proposed another theory: that the biggest problem that local TV faces might not be so much a quality issue, but more a branding and perception issue.

“I think part of the negative perception of local shows is due to ‘cultural cringe’, where we think [international] shows are automatically better by virtue of the fact that they’re foreign. But this isn’t true—just look at Friends.”

Cultural cringe refers to an internalised inferiority complex—the feeling that anything locally produced is inherently inferior, and will only become worthy of praise after it makes it big on the international stage. We only celebrate local productions (like the CNA documentaries) when they’ve won international awards; we only support local actors when they come back after making it big in China or Hollywood. Otherwise, no one really gives a shit.

“Let’s say The Noose, for example, arguably the Singaporean show that made it the biggest because it was Emmy-nominated. That’s definitely making it big. Ilo Ilo winning the Caméra d’Or at Cannes—also making it.”

What Rachel is saying is basically this: Singaporeans refuse to watch local TV because they perceive local TV as being trash. Because of this, local productions fail to attract funding and talent. As a result, they actually become trash. The only way for local TV to break out of this vicious cycle is to receive external validation overseas. But this is difficult because part of what makes local TV programmes unique is their focus on Singaporean stories and Singaporean issues, which may not resonate much with overseas viewers.

While issues like bad acting, bad dialogue, and bad scripts can be fixed, the self-fulfilling prophecy of the perception problem is arguably more damaging for the local TV scene in the long run.

THE EXPERIMENT

As an experiment, I got a few similarly-aged friends to watch the first episode of either My Guardian Angels or one of the two other dramas that Nicole recommended, before telling me how they found it.

Bluetick won this popularity contest hands down with its unusual murder-mystery premise: a man attending his deceased friend’s funeral sees one of the other guests sending a text message to the deceased. To his shock, the message shows a ‘bluetick’, indicating that the recipient has read the message.

“Really, really cool premise!” said Xinyu, who has a passing knowledge of Channel 8 dramas because her grandmother tends to keep them playing in the background. “I remember the trailer vividly precisely because the concept of an unexpected ‘bluetick’ was so intriguing.”

However, she felt that there were points where the drama was too slow—“[They] could have packed a lot more suspense into those thirty minutes?”

She also isn’t sure if Bluetick can be considered a “full Mediacorp drama”, since it was a collaboration between Mediacorp and Viu TV, and is labelled as a ‘Toggle original’. (Toggle has since been rebranded as meWatch). However, she is heartened to see Mediacorp trying to experiment with new themes.

“Yes, because it’s not your typical 9 PM Mediacorp show,” answers Chloe when I ask if Bluetick changed her initial perceptions of local TV. “Like not the family drama kind. Also, there are Hong Kong actors in it and it seems more high-budget than usual.”

“I liked the cliffhanger,” says Brendan Mark, 17. This is Brendan’s first time watching a Chinese-language Mediacorp production.“Done very annoyingly and now I want to watch episode two, but that means it’s done well.”

Despite his appreciation for the plot, he found the cinematography—especially the frequent panning shots—to be sorely lacking. In his words, “It feels a little unpolished.”

Brendan’s perception of Mediacorp dramas has changed “a bit for the positive” by this experience: “Initially, I didn’t think there was very much beyond cheesy romance dramas, but this sounds quite interesting! Though also absurd.”

While it’s true that Mediacorp dramas still have a way to go, they may not be the utter trash that most locals believe them to be without having given them a chance.

“I think now more than ever is a good time to boost those areas of the arts and entertainment in Singapore, because it’s in these dark times that people are really turning to entertainment to cheer them up,” concluded Rachel. And she’s right—after all, if not for the circuit breaker, I’d probably never have given Mediacorp dramas a chance.

Local TV’s niche in the oversaturated television industry is its ability to capture local stories. These are shows featuring Singaporean faces and uniquely Singaporean problems, from the PSLE to running a traditional coffee shop in a Tiong Bahru shophouse. They are, to use a word my generation likes to throw around a lot, more relatable.

As exciting as foreign productions might be, local TV simply resonates, or at least has the potential to resonate, more at its core. Perhaps what local TV needs to do is to stop chasing the latest trends in Korean and Mainland Chinese TV, and just focus on making its programmes as authentic and relatable to local audiences as it can.

To be fair, local TV is starting to move away from trite stereotypes, making progress towards developing more nuanced characters. Slow progress, but progress nonetheless.

“Channel 8 dramas are beginning to address more and more issues faced in society, and it’s really growing out of the past ‘skirting around’ of sensitive topics,” remarks Tay Jing Xuan, 17.

She points to some recent examples from Channel 8 dramas: the discussion of mental illnesses in Mind Matters (2019) and the depiction of a trans female character in 29th February (2018). And in My Guardian Angels, one of the female protagonists is the single mother of a child with ADHD. Such a character would have been deemed too controversial for a Mediacorp drama just a decade ago.

Sure, the single mother gets back together with the father of her child by the end of the drama—in a mushy wedding scene, no less—and the drama’s primary purpose in including the character with ADHD seemed to be to raise awareness about what parents of special needs kids could do to help them, rather than to comment meaningfully on the acceptance of special-needs kids in Singapore. But characters like these show that Mediacorp is, at least, trying on some level to be more inclusive in its programming?

So is there hope for local TV? Two months ago, I would have said no. But now?

Mediacorp dramas may not be up there with the Money Heists and The World of the Marrieds. But perhaps in a decade or two, they could be. The change is slow, but it is happening.

I remain optimistic.

What are your thoughts on local television? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.