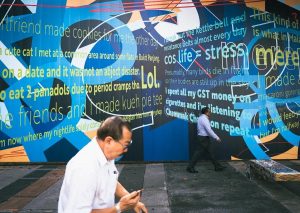

Top image via Unsplash.

I have thought that I could read people’s minds, that I could control animals, that I was going to defeat Trump and become the next president of America. I’m not even American.

I have bipolar and I am my greatest danger. One of the defining traits of a bipolar manic episode is the feeling of invincibility, like your amygdala deciding to go on an indefinite sabbatical.

Early November last year, I was escorted from my holding cell in the police station to a small examination room, where a doctor sat behind a desk. I was wearing broken jeans and a Uniqlo heat-tech t-shirt, which were soaked. I scowled at the doctor. I’m a criminal, I thought, I’m not sick.

“You swam across the Singapore river?”

“Yeah. And back.”

“Why?”

“Because my bag was on the other side,” I said, rudely, thinking it a stupid question.

The doctor laughed and looked at his phone. He typed something into it and scrolled for a bit.

“Excuse me. Taxpayers are paying you.”

He looked up and smiled.

“I was just checking to see if you were on STOMP. Luckily you’re not. The last person documented to swim across the Singapore river was in 1991.”

“Stupid guy,” I said, with a complete lack of self-awareness.

The other defining characteristics of bipolar are high levels of energy, racing thoughts, irritability, impulsivity, and the need for less sleep. I have a severe form of Bipolar I, with rapid cycling, which means that in a year, I may have a manic episode, a depressive episode, a hypomanic episode, or a multiple of each. Bipolar is mainly due to genetic predisposition, and triggered by trauma or long periods of stress. It affects about 1 in 100 people, and those who have it have twice the risk of early natural death by means of lifestyle and the side effects of medication.

I’ve walked into strangers’ homes and knocked three times on their stone garden gnome, thinking it was a message to unlock the next gameplay. I’ve followed a musician into his motel room, asked him to sing me a song, and left. I’ve slept on the streets in Melbourne’s winter, where I was teaching English in high school, with nothing in my bag but paper, whiskey, and a blanket. I’ve spent 5 months all day on Twitter, tweeting at strangers who I thought were people I knew in real life.

I lived in San Francisco in 2015, where I was running a startup based on the computation of persons’ body measurements with a selfie based on reverse engineering. I was losing my self and my mind at the same time, reading texts on ego death and science fiction on simulation theory, challenging my own free will. At one point, I thought I was literally dead. I was euphoric and devastated. I wasn’t sure if I was in heaven, hell, or purgatory. All I knew was that I could not go home. When my family WhatsApped me, I imagined them writing these messages on incense paper and burning it at Mandai columbarium. I asked a friend when I had died. He replied with this:

“We are in purgatory. There will be monsters coming after you, so you’ll have to stick close to your friends.”

Then, when he realised I wasn’t joking, he brought me to the hospital. At the hospital, my sister called. I hadn’t spoken to her in a long time, and her accent sounded really Canadian (her boyfriend, who she was living with, was Canadian).

“You’re not Mei.” I kept saying over and over again.

“Of course I’m Mei,” she kept saying over and over again.

I slammed the phone against the wall, intensely distressed by this imposter who was pretending to be my sister, who I really did miss sorely.

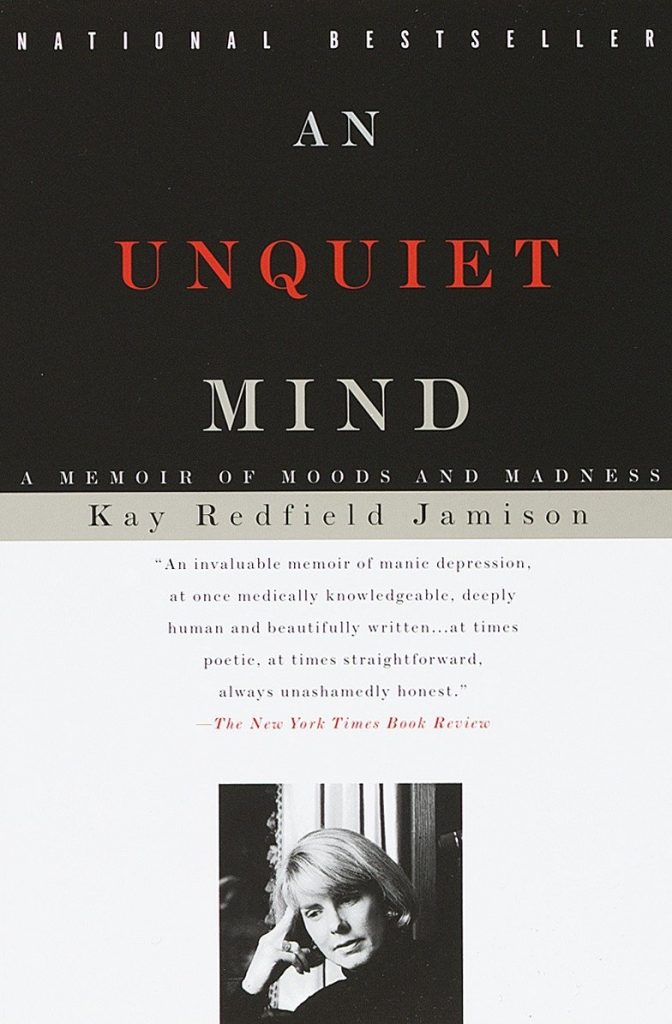

Kay Jamison, who has a doctorate specialising in the field of bipolar disorder, and wrote many of its definitive textbooks, suffered from bipolar. She ended up writing an autobiography, An Unquiet Mind, which helped me come to terms with having bipolar.

Bipolar is an immense journey. In the offbeats of the funny stories, lay a grief so deep that I felt I deserved to be on the streets. There was also terror. Terror about the state of world affairs, paranoia about people intending to harm me, and most of all, the blind searching for an answer to my existential problems. I have thought about suicide many times, and called the Samaritans of Singapore (SOS) hotline sobbing because I could not talk to any of my loved ones about this. How disappointed and betrayed they must feel, I thought, to hear that I was contemplating ending my own life, my life, a gift which is absurd in physics, but made real by our experiential bliss and suffering.

Notable figures with bipolar have committed suicide. Robin Williams, Brody Stevens, Carrie Fisher, Virginia Woolf. This was all despite being extremely accomplished. Brody Stevens was even an advocate for mental health.

There is a tendency to romanticise mental illness, especially mania. But I will not hold onto the diagnosis as the primary feature of my life. It does not define me, even if it takes a gargantuan effort to manage it well.

Currently, I have better care of my condition, as well as the awareness to check myself into NUH’s psych ward for a couple days when the depression or mania starts to act up. I keep a log of the medication I take, as well as significant events that trigger an unstable mood. Despite having mania and depression, I do not take antidepressants because it bears the risk of triggering a manic episode. During cold wintery depressions and hot racing mania, I take the same dose of lithium, a mood stabiliser. I once told another patient in the hospital that I was on lithium. He then said, “So essentially you have a lithium deficiency?” I thought it incredibly hilarious.

Our physiologies are not quadratic equations, unfortunately, which makes us both fragile and complex.

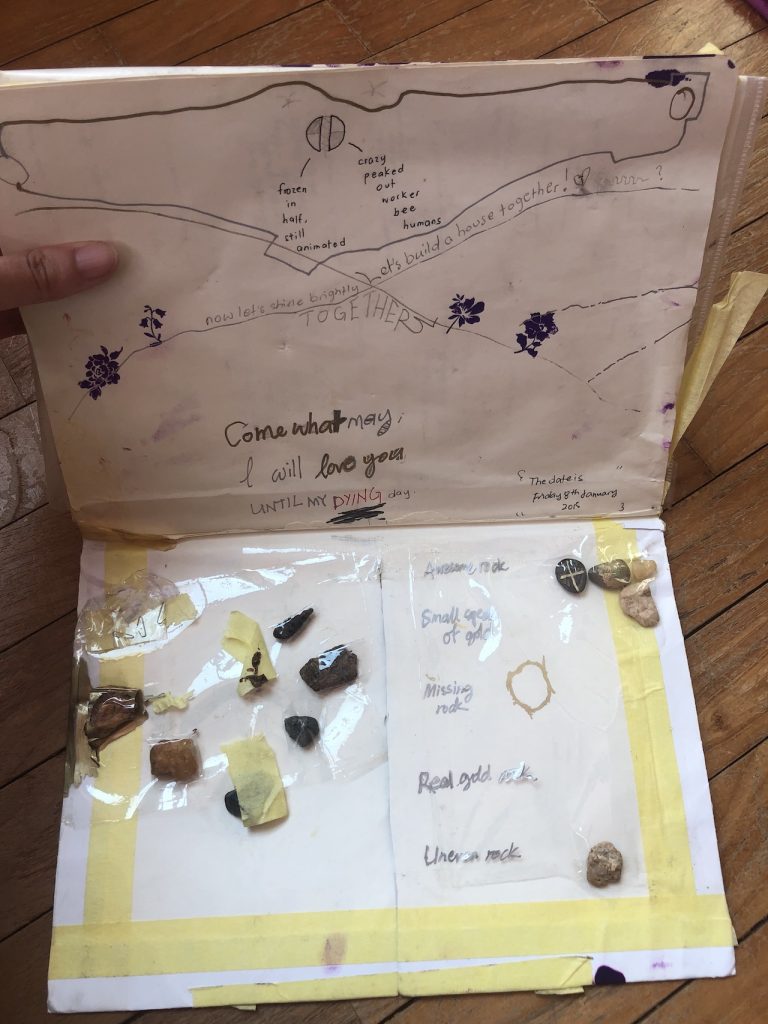

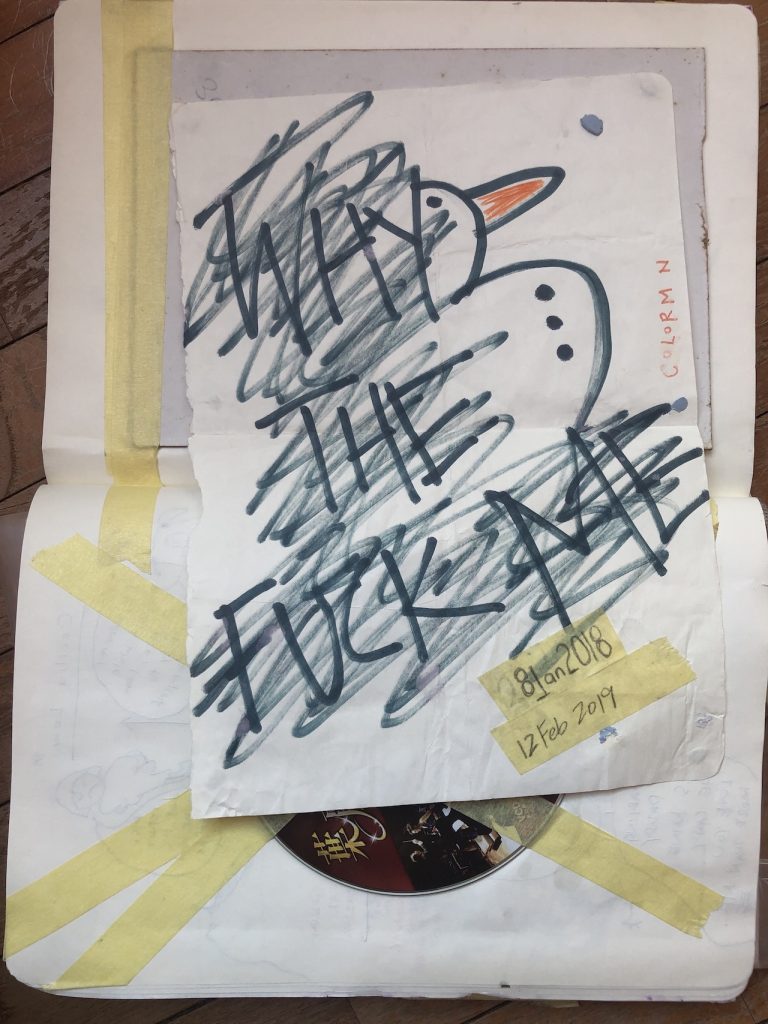

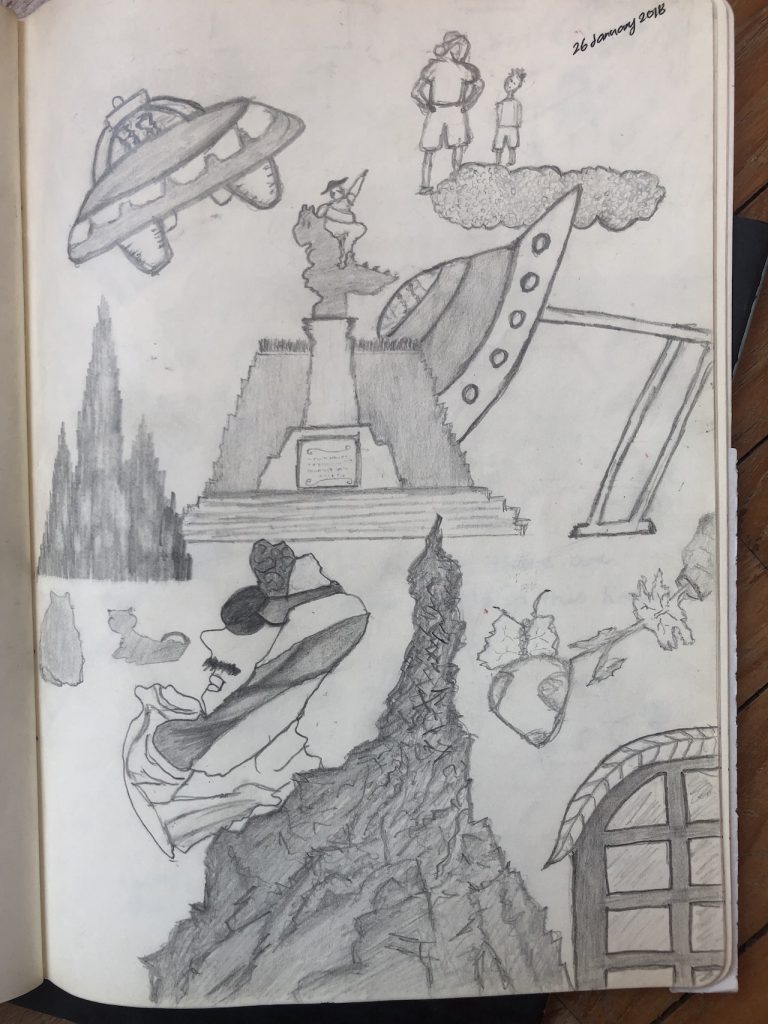

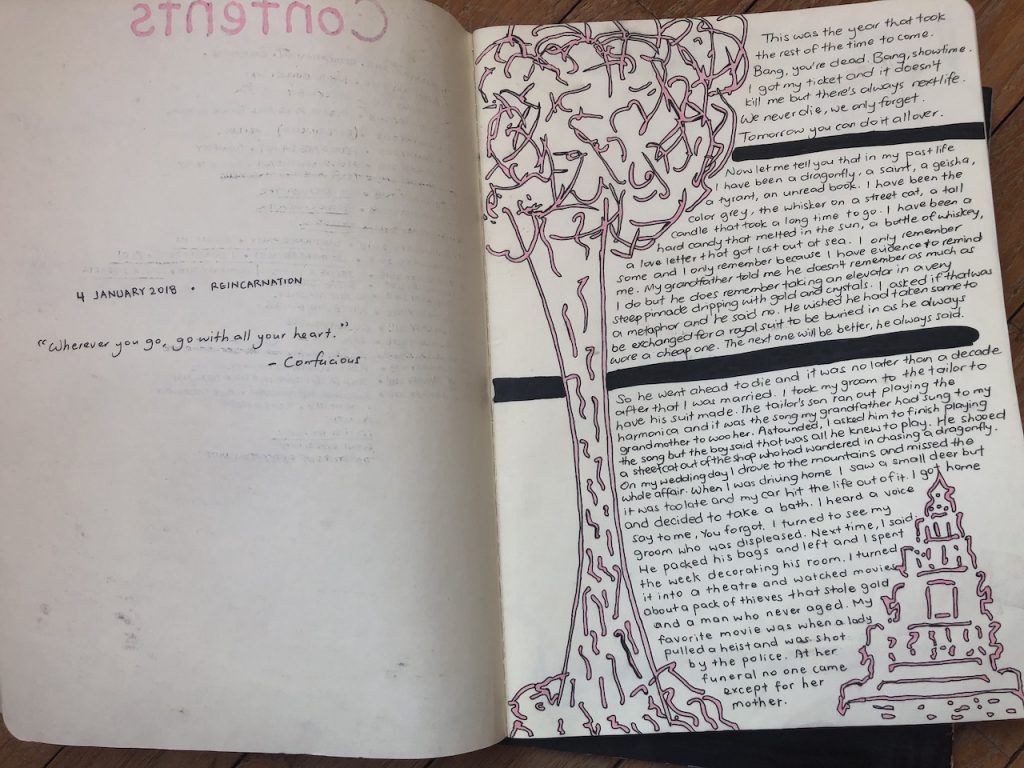

When I’m in mania, I channel the energy into making music videos, writing, and walking. When I’m in depression, I exercise more frequently, complementing daily morning walks with a swim in the evening. I spend more time with people who care, with people who I’ve known for a long time, people who can clearly see that my behaviour during an episode is not the person that I’d always been. I’ve also plucked up the courage to go through my old notes, drawings, and journals from when the bipolar began to flare up. By looking at the indecipherable cryptography which must have appeared pertinent and brilliant at the time, I’m able to remind myself of the unreliability of my judgment.

I arrange the books on my shelves in a relational manner. My core philosophy hangs in three separate notes beside my bed. And on a navy blue feature wall, there are pictures from National Geographic magazine, of a cougar, black bear, mule deer and a snow white weasel. Below it is Darwin’s exploratory drawing of the tree of life, then labelled the coral of life (because of its extinct branches at the bottom), with his famous handwriting, “I think”.

Having rapid cycling from being extremely curious and distractible to being extremely bored and indifferent, my room—this space—helps me focus. As in the principles of minimalism, intentionality in the use of physical space really does help. For example, I’m totally interested in the American elections, but it’s also really none of my business, so I’ve put a coral of the primary candidates on the far wall from my desk, a reminder of this ongoing event that is a secondary interest.

I am not disabled. I have a condition that is difficult to manage, but not impossible. As a writer, I looked at it as a twisted blessing. What better condition could I order from the kingdom of plausible sickness, than one which afforded me the ability to feel the hopelessness of millions, as well as the grandiosity of millions? What condition could be more funny than one which convinces you one minute that life is everything, and the next that life is nothing?

Of course, the stories of my manic episodes are funny; cocktail dinner party anecdotes. But the reality is that they did not take place in fiction, but in the real world; in my real life, with people who were worried sick and stressed out trying to take care of me.

There is a term for people grieving the ones they love, who haven’t passed away, but have lost their presence of mind due to dementia or mental illness. That term is “ambiguous loss”. This is what my family has gone through, and what my closest friends have witnessed. Even after I moved back home and was living with my family, it was as if I had died: the daughter, the sister that they knew was gone, and some stranger’s soul had taken over my body by force, yelling at them that it was all their fault I was this way, that they were bad parents, that I didn’t belong with them but back on the streets of San Francisco, with my real family. Lacking the ability to be responsible for myself, I blamed everything on them: all my unhappiness and all my failures.

My cinematography mentor in Los Angeles said this. At the end of a good movie, everybody is wrong. This is true here, in this story.

My parents had insanely high expectations of me, and I reacted childishly by being reckless with my life, being careless about my education, acting completely antithetical to the daughter they wanted me to be. They wanted me to be polite and caring, and I was rude and aggressive. They wanted me to have a successful career, and I picked fights at every full-time corporate gig I got, until I got fired, or was asked to resign. They wanted me to get married and have children, and I turned down every marriage proposal without considering it.

At the end, we were all wrong, and we were all fine. At the end, we were all trying our best in the throes of the brutal sickness. And at the end, they were the ones who loved me courageously through the long haul. Who while fighting with me, were fighting for me. This proof of unconditional love was a holy truth. And now, my gratitude and redemption manifests in my efforts to take care of them as they near retirement age. One can repent without being guilty. My bipolar condition isn’t my fault, but now with insight into my behaviour during episodes, I can take responsibility for the things I say, the way I act.

It is such a big part of my life, but it is not the core of who I am. Who am I? I’m endlessly curious, I’m endlessly sensual (not sexual), I’m endlessly strong. I have been through months of catatonic depression, specified and generalised trauma, three arrests (without charges), and 8 hospital admissions.

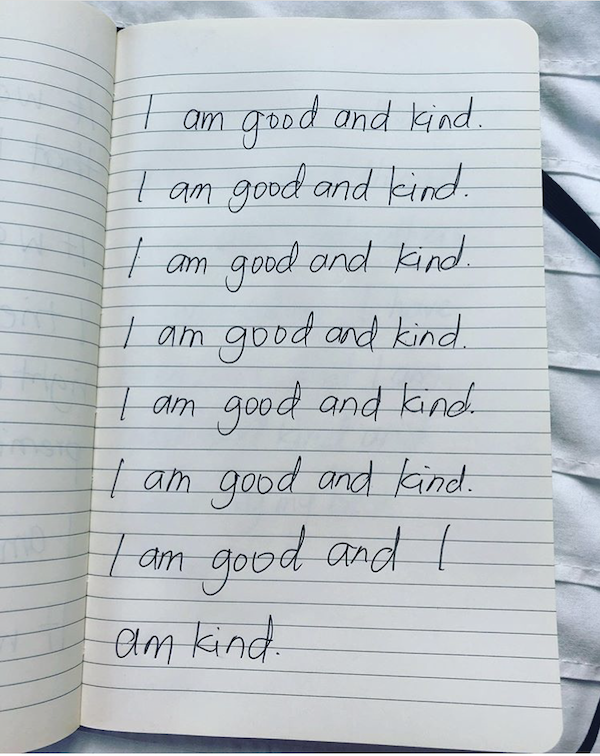

And now, I’m fearless but not reckless. The hurt is here. The hurt is no longer screaming and running barefoot on broken glass down the streets, throwing myself in front of moving cars. The hurt is the soft feeling of my breath as I lose myself in the music of Mozart’s K. 465: Dissonance. It’s the days where I sit at my desk and no words come to my mind, so I practice the penmanship for a curated soul, writing over and over in my journal the words: “I am good and I am kind.”

But the hurt is good. As Jim Hopper said in Stranger Things, “It means you’re out of the cave”. We all have this, the human condition. If you care, and when you care, you will hurt. In a world where fascists, misogynists, and the callous rich roam, being a little sick is perfectly normal. My friend was right. There are monsters. But it is not an all pervasive reality of cruelty like hell, nor is it the cathartic reality of heaven. It’s something in between. There is suffering, and there is redemption; a purgatory.

In this brutal sickness, there were progressive facets of struggle. The reckless behaviour, coming to terms with my diagnosis, and the immense sadness of losing friends. I will walk, I will read, I will write. I will observe the thoughts I have about being talentless, loveless, and useless. I will not depend on anyone for my happiness, even if my well becomes dry during this parched season. I will drink water wherever I can, I will walk miles to find a river, a stream, a trickle of serotonin, or whatever the hell runs my juice.

Stability has to be earned through hard work and patience. I will always have bipolar. Like the seasons, I will march on.