What does it mean to be Singaporean? Many will say that being Singaporean means speaking Singlish, or being kiasu. But in recent years, it can feel like being Singaporean is all about being in a constant state of change—constantly measuring trade-offs against bets on future growth, having to re-establish our identities as the spaces around us face a seemingly never-ending cycle of being torn down and built up, taking with them intimate memories and slices of our culture.

This story is part of a series where we explore the spaces, subcultures, and stories of Singapore that may no longer exist as we pursue urbanisation and progress. It’s not just about conservation and nostalgia, but also about understanding why, as a nation, these transformations are sometimes necessary.

Golden shafts of light line the pale pink walls, casting quivering shadows of trees jingling their sleeves of green. As the mynahs trill, a sense of peace settles snugly over a cluster of five-storey HDB blocks in Siglap. Supposedly due for demolition under the Selective En Bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS) in 2015, the four stout blocks still sit solemnly along East Coast Road today, its empty hallways and vacant grounds a queer sight amidst the neighbourhood.

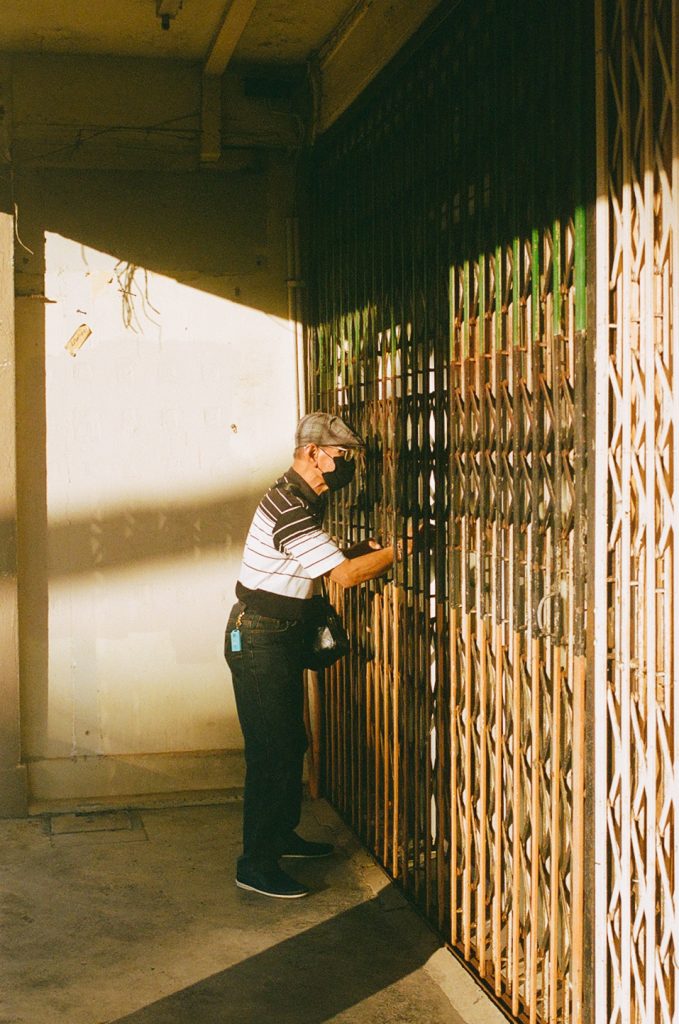

This curious compound is very much the lesser known Dakota, sporting the same apocalyptic qualities, now that residents have all but emptied its quarters. Dated posters are splashed against dusty storefronts, obnoxiously publicizing telco offers or coyly showing off the latest sultry hairdo. Void of their original inhabitants, mailboxes are stuffed full with an assortment of leftover flyers, plastic bottles, and other alien intruders. A mishmash of wooden boards are deftly nailed to windows and entry ways, while hefty locks coil around grills with their paint peeling off, a warning to the stray explorer.

A former kampung, the Siglap flats were built in response to a case of Chinese New Year festivities gone awry, when a blazing fire in 1962 consumed several attap houses. The new flats to rehouse affected residents were completed in 1964, consisting of a mix of residential units and shop spaces.

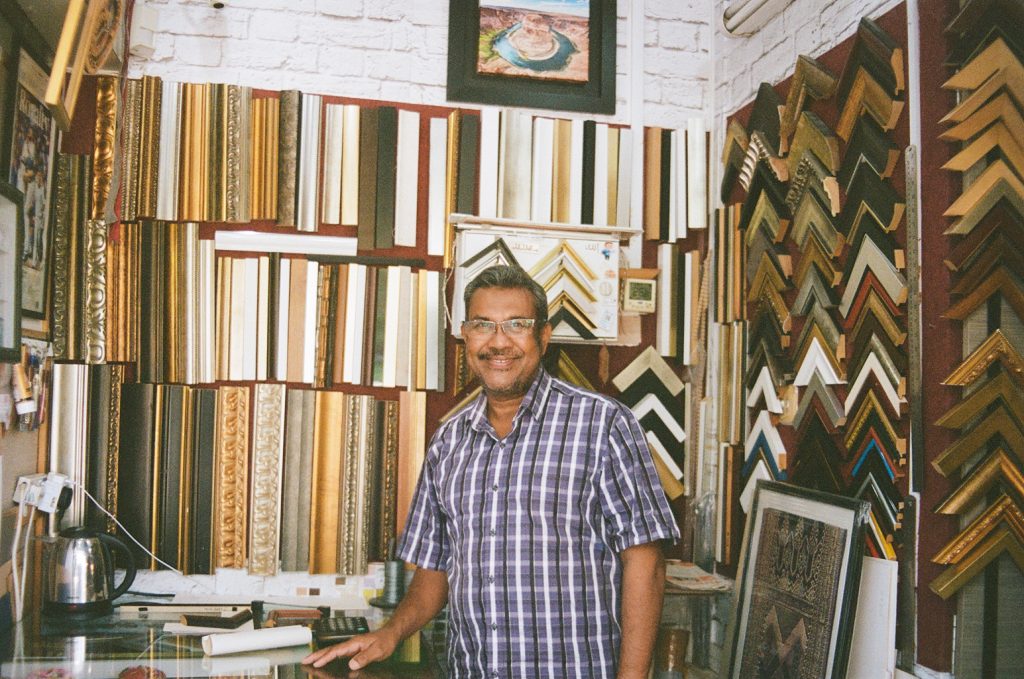

Setting up Framer’s Choice some 20 years ago, Mr Kadir was one such former tenant before he moved to a corner unit at Siglap Centre. With a wealth of experience in frame making, Mr Kadir is one of the few craftsmen in what he labels as a dying trade.

“Last time when I’m missing a material, I can just call my frame-making friends to ask if they have spares. But now, less and less friends,” Mr Kadir muses. He is seated amid a stack of frame samples lined up like a searing arrow, with a jumble of tape, receipts and other handy tools crammed on the neighbouring shelf.

Mr Kadir’s brother was the one who first showed him the reins, and the two shared a frame making business together.

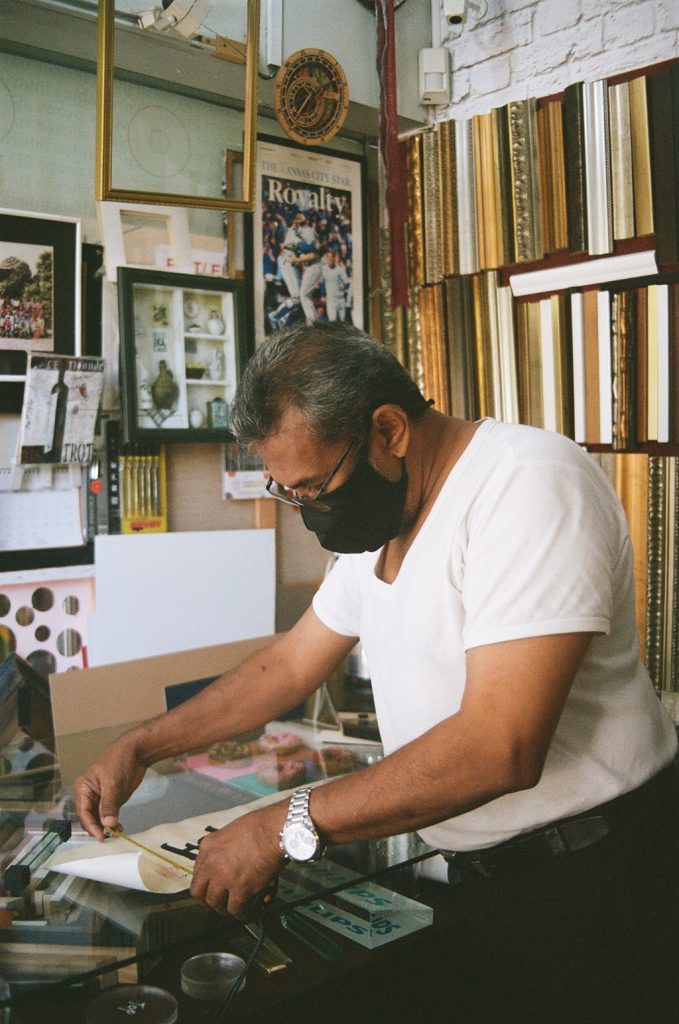

“It was tough at first when I didn’t know anything”, Mr Kadir shares. Gesturing to his palm, he explains, “I would get my hand cut on glass, cut here, cut there, all bleeding.”

Mr Kadir has framed all sorts of knick-knacks, from Ming dynasty replicas to Nyonya beaded sandals. He claims there is no secret to frame making, but expertly recommends a medium tone wooden frame with a thin gold line for the chinese calligraphy scroll I brought.

As talk turns to life at the Siglap flats, a glimmer of nostalgia enters Mr Kadir’s voice.

“All the ground floor shop owners were friends,” Mr Kadir reminisces. “Dr Wong, his clinic was just beside my shop, so he actually helped me to get many customers. Whenever people visit him, they would see there’s a frame shop next door and come in to enquire.”

“When I had to move out, I felt, how to say,” Mr Kadir ponders, searching for the appropriate word. “Uneasy, I felt uneasy.”

I ask if he still keeps up with the other folk, but he shakes his head, telling me that they all lost contact. “Every now and then, I’ll hear that someone passed away,” he says softly. “Like that la, old already.”

One friend, however, made the move to Siglap Centre with him, setting up a salon in the basement of the creaking building.

Always sporting a hat of some sort, Uncle Sam, as he is affectionately known by his customers, is an unmistakable sight at the salon. Picking up the tricks of the trade from his father at the tender age of 18, the exposure sparked off a journey that would see Uncle Sam move from salon to salon to garner experience, before finally opening Siglap 5 as his own.

He readily offers an explanation for his shop’s name, pointing to a framed poster of a Malay band.

“My friend’s band back in the day was called Siglap 5 and I really liked their music,” he says.

Stepping foot into his salon is akin to taking a trip back in time, with walls peppered by retro looking posters of local bands from the 60s and old school barber tools strewn over the counters. He even has a sleek, black electric guitar hanging on the wall, a relic of his distant musical past. “Now my hands cannot press the chords la,” says Uncle Sam.

In fact, Uncle Sam used to belong to a band, but he abashedly brushes me off when I ask about their songs, insisting that it was merely for fun. “It’s just for the photo,” he humorously quips when I point out his guitar wielding self in the faded print.

A constant stream of customers flow in and out of his shop, “How are you”s and smatterings of Malay echoing throughout the basement. Experienced folk help themselves to plastic stools stacked by the side, and sit by the corridor waiting for their turn on the black leather chair. The tune of Seruling Anak Gembala, one of his favourite tracks, reverberates as he nimbly works scissor and razor.

Malay tunes are swapped out for cartoons on his iPad when little Nicholas gets his hair cut. Uncle Sam personally hoists the young boy up on the barber chair, and confidently snips away. I ask Nathaniel, his older brother (who has been narrating an adventure from The Land of Stories to me), why he likes coming to Uncle Sam.

“Because …” he says shyly, “he gives me sweets!”

I wonder how the move to Siglap Centre has been for them.

“Totally different,” says Mr Kadir as he shakes his head, forlorn. “Last time, I can just go out under the big tree and sit at the chess table outside, chit chat. Now here I feel so cramped,” he adds, gesturing dispiritedly at the tiny corner his shop now occupies.

In a bid to reminisce about old times, we cross the street to walk along the foregone pathways of the Siglap flats. The faded storefronts bear testament to the life that once existed, an ode to the hair salon and the photo studio, the coffee shop and the violin store. The banter flows naturally between the two, with Mr Kadir impishly dishing out a schoolboy refrain of I don’t want to sit near him when I ask them to pose for a photo together.

On our evening stroll, we discover one of the doors left ajar, and cautiously peer in. I am beyond myself with curiosity, but the two of them are nonchalant.

“This one the owner pass away already,” Uncle Sam says. Surprised, I ask how he knows, to which Mr Kadir interjects, “This fellow knows everyone here!”

When asked about the kampung spirit, the pair enthusiastically gush about the good old days, voices overlapping one another as they speak. The kampung spirit has always been a rather elusive concept to me, a distant mantra rather than a lived experience, an elevated synonym for courtesy and awkward neighbourly bonding.

“Kampung spirit is real, you not part of kampung you don’t know,” Uncle Sam chides. “Last time 5km down the road, whose son whose brother I also know.”

“Next to my shop, there was this auntie selling joss sticks and traditional Chinese items,” Mr Kadir said. “She would always help to jaga my shop when I need to go out, and when customers come she will help me to tell them to wait. After the work day finishes, she’ll always tell me to go home safely, I always remember that.”

We hear of a neighbourhood’s demise all the time. A season ends, shops shutter up, residents move on. In my own homeground of the Siglap-Katong area, storefronts are always changing rapidly, with new tenants swiftly occupying jilted spaces in hopes of a different fortune. With the kaleidoscopic changes come an amnesia that seeps in unconsciously, often climaxing in the shuddering realization that we no longer remember what previously occupied the space where the shiny new cafe now sits. While I welcome the plethora of coffee options now bestowed upon us east siders, I cannot help but feel a pang of worry about the creeping homogeneity slowly encroaching neighbourhoods like Katong. It is the relentless tug of war, the tension between preserving a slice of old history and welcoming a new chapter of modern development.

There has always been a tint of artifice to nostalgia, a lament for the bygone days seen through rose tinted lenses. We clamour for second hand bookstores to stay open even though we rarely patronize them. Or bemoan the loss of kampungs we have never set foot in. Yet, there exists a group of people who are well justified to lament, a community for whom the treasure trove of memories does not simply exist as a caricature. Places breed relationships, and the relationships fostered at Siglap flats are real to both Uncle Sam and Mr Kadir.

In Tan Pin Pin’s film In Time to Come, the fanfare accorded to stately milestones is contrasted with the ordinary, quotidian moments often swallowed by the headstrong rush toward productivity. The glittering sea of camera flashes anxious to capture the opening ceremony of the Downtown Line is contrasted with a mundane shot of commuters sprawled on the train, a subtle critique on our biased curation of what is “worth remembering”.

The film goes on to chronicle the exhuming of a time capsule from the past, and a making of a time capsule for the future, where the objects both uncovered and prepared are ironically the inconsequential—a telephone book filled with obsolete addresses, a life jacket peppered with unidentifiable signatures. It is regrettable that when in preservation, focus is given to the ordinary, yet in present life one remains shockingly unconcerned about the commonplace.

Thankfully, the excavation of a place is rarely sufficient to uproot the totality of memory, as Mr Kadir and Uncle Sam have so proven.

“Of course sad,” says Mr Kadir when asked about how he feels now, but then adds, “so that’s why you must give me the photos you take.”

“You must be happy when you’re cutting hair,” Uncle Sam chirps, “cannot be unhappy.”

Is there a place in Singapore that’s about to be forgotten? Tell us all about it at community@ricemedia.co.