This is a cliche repeated so often that it no longer has any meaning. We know that Lee Kuan Yew wanted Singapore thus and we can see the rows of neatly planted trees. But familiarity breeds contempt, so we barely register their presence as we go about our lives.

This shouldn’t be the case because ‘Garden City’ is not just a marketing catchphrase, but the truth. Much has been written about Singapore’s strategic location as a port and blah blah blah, but little is said about the economic contribution made by our trees.

The ubiquity of ‘Garden City’ sloganeering has all but obscured the reality that Singapore IS a ‘Garden Nation’. Singapore’s destiny has been (and continues to be) shaped by the trees that grow here. And not because Ah Gong say so.

The mangrove forest hosts many salt-tolerant species, but the most useful amongst them is probably the Nipah Palm a.k.a. Attap. Found further inland, where the sea gives way to freshwater, the Nipah/Attap is an essential ‘tree’ for pre-colonial Singapore. Throughout Southeast Asia, the attap is the basic building block of a kampung because the large palm fronds can be made into roofing for your attap hut, or weaved into baskets, hats and other useful items.

Aside from dope hats, the tree’s sap can also be made into a Gula Melaka-like sweetener called Gula Apong. It is supposedly more fragrant than its Malaccan cousin, but we will never know because it is a) labor-intensive to produce and b) rarely eaten outside of Sarawak.

Although the Nipah Palm can still be found in Pulau Ubin or Tekong, it is no longer seen, even in Kampungs. Writers note that Bukit Ho Swee and Kampung Buangkok had attap housing, but fire reduced the former into ashes while zinc roofs have long since replaced attap in the latter.

The incredible value of nutmeg was due to its scarcity. The tree grows only on Maluku ‘spice’ islands (Indonesia) and export was controlled by local kings. Arab/Indian traders brought it to Malacca, where it was bought by Portuguese sailors and shipped back to Europe via Sri Lanka, then South Africa.By the time it disembarked in Lisbon, nutmeg was basically spicy cocaine, sold at 300 times the production cost.

In the 1600s, the Dutch East India Company got tired of haggling with middlemen and decided to violently subjugate the region. They conquered the Moluccas, killed everyone on the islands and monopolised the spice trade once and for all.

That is, until the British arrived, also in pursuit of nutmeg and also ready to shed blood for spices.

Thus, it comes as no surprise that Nutmeg became one of the first trees cultivated in Singapore. Raffles planted Nutmeg in the area around Fort Canning immediately after claiming Singapore. It flourished, causing nutmeg plantations to crop up in Singapore, Sri Lanka and further afield.

Although changing tastes and oversupply eventually crashed the nutmeg market, it can be argued Singapore would not have happened if not for the Nutmeg Tree, whose strange and bloody fruit brought the Europeans to SEA.

While commercial rubber trees were found only in Brazil, but British spies smuggled it back to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. The tropical plant did not grow well in temperate England, so it was forwarded to Singapore Botanic Gardens in 1877, where they were taken under the care of Scientific Director Henry ‘Mad’ Ridley.

At Cluny road, Ridley developed a superior ‘wound response’ technique for tapping rubber trees and promoted rubber planting at every opportunity. Unfortunately, he had a rather low EQ and everyone in the colonial government ignored the ‘Rubber Crank”s rants on how RuBbEr Is dE fUTuRe.

Despite a lack of initial interest, Ridley’s Rubber advocacy was eventually taken up by a Chinese tapioca planter named Tan Chay Yan, who starting planting them near Melaka. Within a few years, demand for rubber seeds exploded and the Singapore Botanic Gardens could barely keep up. The 98,000 rubber seeds sold in 1898 grew to 157,000 rubber seeds in 1901 and eventually 837,500 seeds in 1911, with orders coming from as far afield as Nigeria and Cuba.

In short, Rubber was the OG start-up unicorn.

With 20 years of Tan Chay Yan’s first crop, the scant 345 acres of rubber trees in Malaya became 2.3 million acres. Malaya supplied half the world’s rubber and the Singapore Botanical Gardens became the leading distributor of rubber seeds. In Singapore, rubber trees could be found everywhere from the Istana to Ang Mo Kio to Pulau Ubin. Much of it was exported to America for use in the burgeoning automotive industry.

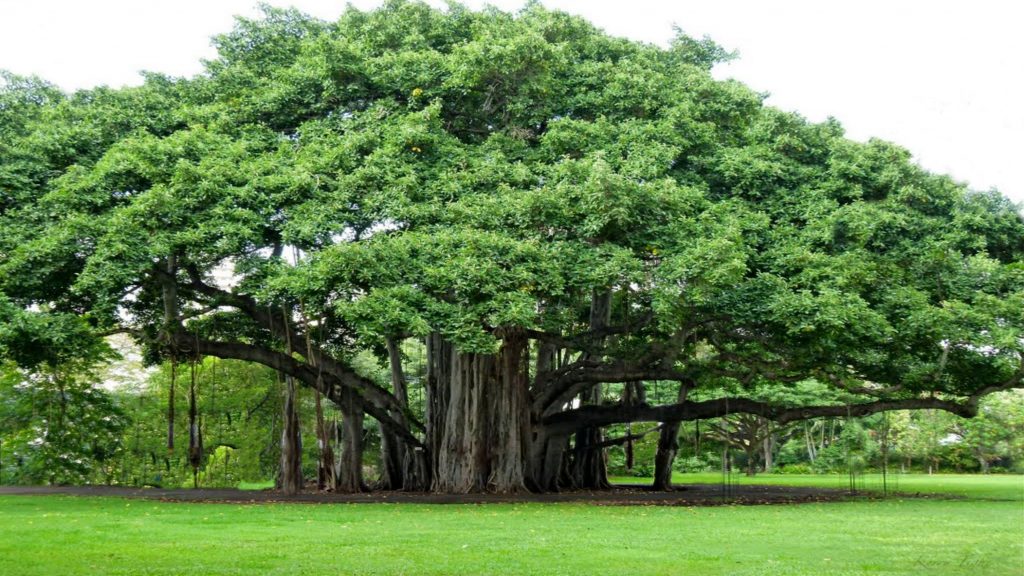

I am referring of course to George Yeo’s infamous 1991 speech comparing the PAP government to a Banyan Tree. Trees are usually flattering metaphors because they stand for rootedness, shelter and all that good stuff. However, George Yeo’s choice of a Banyan—a strangler fig—complicates matters because Banyan Trees are parasitic in nature. They graft themselves onto a host tree, compete with it for resources, and eventually kill the original host. The foliage of the Banyan is so dense that it prevents other leaves from getting any sunlight.

Just as Banyan Tree throttles its host alive, Singapore’s nanny-state was strangling the civil society it governed. Hence the need for ‘pruning’, so that Banyan and host (i.e. PAP Government and society) could happily co-exist.

Kudos to George Yeo for calling out our government’s most repressive tendencies with the most elegant of metaphors. Although the analogy is 37 years old, it remains relevant today because the central tension between authoritarianism (Banyan) and liberalism (pruning) still exists. You can see it in the government’s eagerness to enact fake news legislation and its reluctance to let political opponents be political opponents.

If you ask critics like Cherian George, the proverbial Banyan could probably still use a few more whacks from the chainsaw.

Despite its sheer numbers, the rain tree is not particularly interesting. It has no real commercial purpose like Nutmeg and sorrow awaits the man who tries to build a kampung from Rain Tree leaves. Even when LKY launched his ‘Garden City’ campaign in 1963 to make Singapore green again, he planted a Mempat Tree instead of the more common Rain Tree.

Perhaps the only fascinating thing about Singapore’s Rain Trees is the origin. Like the Rubber Tree, it was an American immigrant, first planted here around 1882/1876(?) to provide shade for plants that wither under too much direct sunlight. Like 377A, caning and the Internal Security Act, the Rain Tree is part of Singapore’s invisible colonial legacy, persisting into the modern era.

Oil palm estates were common in Malaya and Indonesia throughout most of the 20th century. Yet, production never really exploded until the 1980s and 2000s, when Malaysia and Indonesia became the world’s largest producers of palm oil.

The reason is twofold. Firstly, Europe and America passed regulations against trans fats and palm oil is a low-cost alternative with no trans fat. Secondly, the FMCG industry (Unilever, Nestle, etc) gradually found more and more uses for the palm oil. Your ice cream probably contains a sizable pint of refined palm oil standing in for more expensive dairy and so does your lipstick, soap, chocolate, bread and many others.

What does this have to do with Singapore? Well, Peter Lim/Robert Kuok’s Wilmar International is one of the world’s largest producers of palm oil. A great many Singaporean fortunes have been made by investing in palm oil, even if the tree doesn’t grow actually grow in Singapore.

Postmodern trees bear strange fruit and none is stranger than the Supertrees behind Marina Bay Sands. It is a tree that is not a tree, linked by a pathway sponsored by OCBC and decorated with plants that are 100% non-native to Singapore. It grows well if you water it with growth-hacking and it can drop immense PR gains, including but not limited to 1) a visit by Kim Jong Un and 2) a lengthy cameo in Crazy Rich Asians and 3) a Nas Daily feature.

This is also a tree that resists interpretation. Did we manufacture a tree to show that humans have finally surpassed nature and, thus, God? Has the marketing of Garden City taken over the gardening of Garden City? Are the non-native plants some kind of statement on diversity or a stance on immigration? Is social media the final frontier which must be conquered just as the Dutch conquered the Molucca islands? Is the fruit of ‘exposure’ an imaginary one? Or is it real because our digital lives are more real than our real ones???

Whatever the case, one has to admit they’re very pretty, especially at night. I just hope that tourists won’t tire of Instagram validation the way Europeans eventually moved on from snorting nutmeg.

It may sound strange and pompous, but Singapore’s history is at heart, a botanical history. We are defined not just by people, but also by the plants and trees that live in the spaces in-between. The ‘Garden City’ branding is true, because for so much of our history, we survived by manipulating nature, turning the wild jungle into a controlled ‘garden’, which we could bend towards our own purposes.

I know it’s somewhat ridiculous for an idiot to write on such a subject so let me end with an expert’s quote. The following is from E. J. H. Corner, assistant director of Singapore Botanical Gardens (1929 -1946):

“To write a book about Malaya for all who find beauty and inspiration in the life of the country has been my object. We sorely need books about natural history, whether they be for schools or for grown-ups because, in our exploitation and destruction of natural resources, we must not forget that one mark of civilisation is the regard that men bestow on wild things. It has always seemed to us the duty of biologists to prepare from time to time, books on natural history which will serve as guides and companions above all to amateurs, in whom the flame of knowledge burns brightest, that each generation may play its part in preserving the natural history and the wild life of the country. We have chosen trees as our subject because all the native richness of Malaya depends on the integrity of its forests. If a delight in trees and a respect for their majesty can be created, even in a small body of persons, our country will never suffer the tragic domestication which many lands tamed have undergone. Botanists know too well that when forest is destroyed, the ancient verdure of the earth is lost forever; trees depart in flames and no mantle descends to clothe our ignorance.”