“My name is Koh Kim Hong. I’m 71. I was working as a building contractor and property developer on my own. Gone through ups and downs in my business, but it’s okay, I’m retired now.

I got into contact with Falun Gong, or Falun Dafa, twenty-one years ago, when I was 50. The words that really struck me was truthfulness, benevolence, and forbearance (真 zhen, 善 shan, 忍 ren). I thought to myself: this cannot be wrong! These teachings sound so simple in theory, it is not so easy to follow in practice.

The next thing my wife and I did was go for a nine-day Falun Gong exercise workshop in Singapore. About a month after we finished the workshop, Falun Gong was banned in China and the persecution started. Many practitioners in Singapore stopped practicing because of the pressure. At the time, my wife and I had to sit down to decide whether we wanted to continue. I told my wife: Falun Dafa. Is it righteous? Is it good? Yes. So we didn’t follow the others in withdrawing and continued practicing.”

(The above is an excerpt from RICE’s interview with Mr. Koh Kim Hong, veteran FLG practitioner)

A Brief History of Falun Gong

Contrary to popular belief, Falun Gong is not banned in Singapore.

In 1996, it was legally registered in Singapore as the Falun Buddha Society and remains a legal entity today. The association office is located on a second floor shophouse at Geylang Road, within walking distance of Kallang MRT station.

By current estimates, there are between 500-1,000 Falun Gong practitioners in Singapore, some of whom practice privately and are not affiliated with any organised group.

But knowledge of Falun Gong is surprisingly scarce among Singaporeans. Most young people under 30 years of age have never heard of such a practice, nor are they aware of the controversy that still surrounds it.

Which is why when I received the invite from Mr. Koh Kim Hong, veteran practitioner of the Falun Dafa association to conduct an interview, the reaction from my colleagues was a mixture of surprise and amusement.

“They’re allowing you to take photos?” one colleague asked. “But isn’t Falun Gong illegal?”

“Good luck,” said another colleague. “And don’t get brainwashed.”

Most of these responses are based on misconceptions about the practice that still persist to this day. Over the past two decades, a propaganda war has been waging between Falun Gong and the Chinese government, which has only further obscured the truth. Most notably, Falun Gong publishes The Epoch Times, an anti-CCP newspaper. It is also affiliated with the Shen Yun Performing Arts troupe, a performance that advertises itself as ‘5,000 Years of Civilization Reborn.’ You can read Jia Tolentino’s New Yorker review here.

To summarise Falun Gong’s history based on the generally accepted facts: Falun Gong, or Falun Dafa, is a ‘new religious movement’ that was founded in China in the early 1990s by its leader Li Hongzhi, riding the wave of the ‘qigong boom’ at the time. Qigong is a slow-moving energy exercise that traces back to ancient Taoist practices. In many places with large Chinese communities, qigong is stereotypically practiced in the early mornings by the elderly at public parks.

By the mid-to-late 90s, relations between the Chinese government and Falun Gong deteriorated, as China increasingly viewed Falun Gong’s growing membership as a threat. Founder Li Hong Zhi migrated to the United States years before 1999, when the practice was banned in China altogether. He continued his teachings in the U.S. and still resides there today in upstate New York, in a 400-acre compound called Dragon Springs.

At this point, the accounts get murkier.

Falun Gong practitioners have alleged widespread persecution of its followers in China, including accusations of systematic organ harvesting of tens of thousands of Falun Gong prisoners of conscience. The Chinese government has consistently denied these allegations.

In 2006, an investigative report conducted by Canadian MP David Kilgour and human rights lawyer David Matas concluded that “there has been, and continues today to be, large-scale organ seizures from unwilling Falun Gong practitioners,” although critics of the Kilgour-Matas report point to the circumstantial evidence used to support its conclusions.

In short, while some form of religious persecution of Falun Gong exists in China, the severity and nature of that persecution is in dispute.

As a writer, I’m neither qualified nor equipped to evaluate the truths behind these claims. What I am interested in, however, is the human side of the story: why some Singaporeans find themselves drawn to the teachings of Falun Gong, what its practitioners actually believe, and what they have reaped from its teachings.

This is particularly relevant in the times we’re living in. Whether you’re young or old, this year has had a lot of people trying to make sense of their lives. For some, religion provides them with answers and perhaps more importantly, with a purpose.

Which was how I found myself working Saturday night OT at a Falun Gong exercise workshop.

An Invitation to the Falun Dafa Society

The exercise workshop started promptly at 7 PM on Saturday. There were about a dozen people in attendance, along with 3-4 association volunteers.

Mr. Koh Kim Hong, a veteran practitioner at the association, was there to greet me.

Kicking off the interview, I started off with the basics: what is Falun Gong?

“Falun Gong is about mind and body enrichment,” said Mr. Koh. “Improving the mind means practicing our core tenets of truthfulness, benevolence, and forbearance (真 zhen, 善 shan, 忍 ren). When you upgrade your morality, you have dignity, and then goodness can come in.”

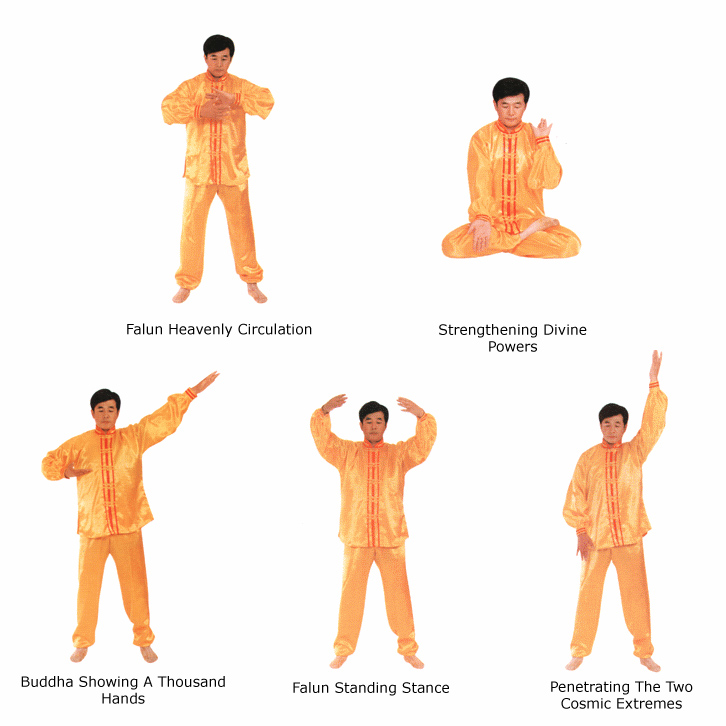

For the body, Falun Gong practitioners have five sets of exercises: four slow-moving qigong exercises and one meditation pose. Practitioners believe that these exercises slow down the body’s metabolism. The theory behind it is derived from ancient Buddhist and Taoist teachings, as well as the principles of qi (energy) that underlie traditional Chinese medicine.

“Through the course of normal human life, some of our acupuncture points are blocked,” explained Mr. Koh. “The exercises we do can enhance our circulation. You will feel healthier. Because you need to be healthy to learn the morality part.”

The nine-day workshop is typically structured as follow: one hour of lectures based on the Zhuan Falun (轉法輪), the religious text authored by its founder Li Hongzhi. This lecture involves watching footage of Li Hongzhi expound on Falun Dafa in a series of nine talks. Volunteers at the association then spend time trying to put these talks in context. Finally, the workshop concludes with a half-hour exercise session, followed by meditation.

The night I arrived was the second to last day of the workshop, and attendees had already gone through most of the lectures. The final day is set aside for “interactions,” where volunteers explain the positive and negative bodily reactions that may have arisen in participants as a result of the workshop, and what this means in the context of their qi.

The general worldview of Falun Dafa is that morality in modern society is in decline and that Falun Dafa is a way to help navigate the mental and physical stresses that this society brings about.

To quote the words of their master Li Hongzhi, “What we are doing is saving people from this world by guiding them to greater spiritual heights.”

Singaporeans Come to Falun Gong Seeking Answers

It became apparent to me that the founder Li Hongzhi plays a central role in the religion.

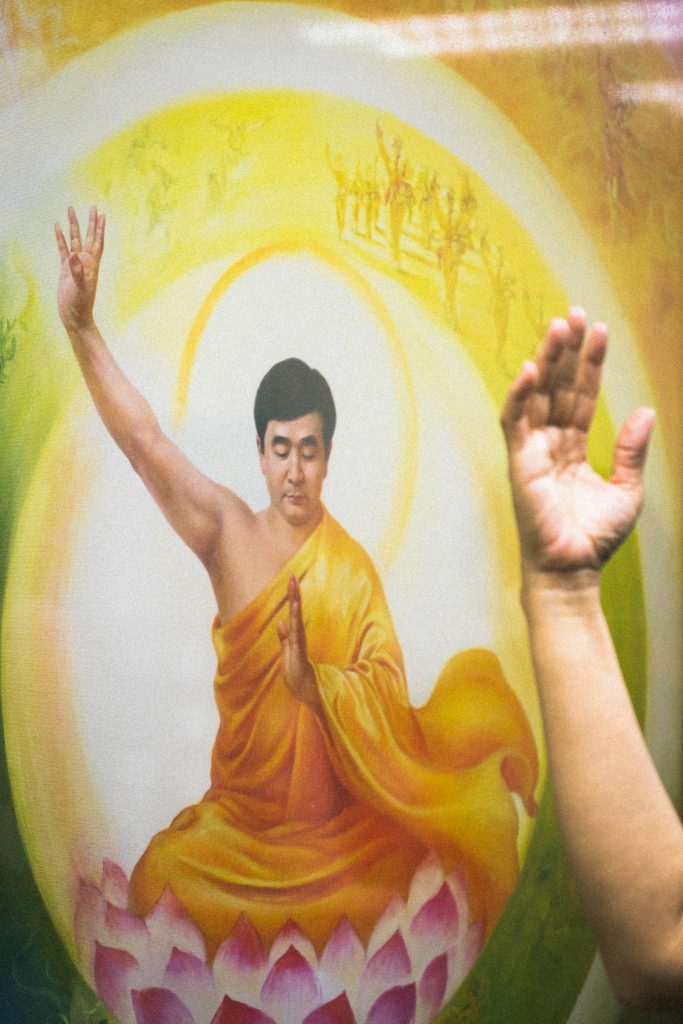

Stepping onto the floor, I observed the art that decorated the walls, where Li’s image is featured heavily. The most innocuous one is a portrait of Li in a suit and tie that’s flanked by two Falun symbols at the front of the room. But there are stranger examples of artistic license, including one where Li’s face is superimposed onto a Buddha, while another depicts the founder with a pair of white angel wings.

As we walked the floor, Mr. Koh shared with me that many who seek out the workshop usually face some sort of difficulty at work or at home: financial, health or family problems. They come to Falun Dafa seeking answers.

I asked Mr. Koh whether he himself was struggling with something when he first joined Falun Gong. He answered by recounting a personal story,

“I’d actually gone through many religions before Falun Gong. Growing up, I attended Christian school and read the Bible. I understand who Jesus Christ was. I really respect him. I’ve gone through Taoism too. I was running a temple for a little while,” he recounted. “But when I asked for answers to the profound questions, I couldn’t get an answer. They’d say it’s a heavenly secret. 天機不可洩漏 (Tian ji bu ke xie lou—heavenly secrets can’t be revealed). But when I read Zhuan Falun, our master explained everything to me. There was no such thing as heavenly secrets.”

Through twenty one years of practice, Mr. Koh began to realise very profound meanings. And now, he hopes to share that knowledge with fellow Singaporeans.

“Falun Dafa teaches righteous moral values and principles, something that is often seen lacking today. Maybe it’s our rat race society,” said Mr. Koh. “It’s too competitive here in Singapore. People have got no other choice!”

But there is no quick path to salvation.

“Some think that Falun Dafa can help solve their problems instantly, but it doesn’t work like that,” said Mr. Koh. “We have to explain to them that the change they seek has to come from within.”

Is Falun Gong a Cult?

Over prata and kopi at the coffee shop downstairs, I arrived at the question that was on most people’s minds: is Falun Gong a cult?

“How can we be a cult?” asked Mr. Koh. “We don’t collect money. We don’t build buildings. We don’t register our members. A cult wants to control its members, so the basic principles of that accusation are wrong. We are a qigong association. People are free to come and go as they please!”

This may be true at least, in Singapore, but there are other criteria for cults too. For example, Falun Dafa seems strongly centred around the teachings of its founder Li Hongzhi. While Li does not outright call himself a God, he has alluded to some measure of divinity as a cultivator of ‘energies’. In the Zhuan Falun text, he talks about ‘divine entities’ that he controls.

I asked Mr. Koh about the founder Li Hongzhi’s claims of levitation, psychic powers, and the healing of illnesses. Mr Koh responded by saying that he has never witnessed this personally. The master Li Hongzhi has reportedly stopped performing such miracles after he fled China, claiming that it had become a distraction to practitioners, causing them to stray from Falun Gong’s moral precepts.

Finally, I raised the question of modern medicine and science. How does Falun Gong reconcile its belief in qi, the Taoist Way, and ancient Chinese medicine with modern medical practices?

“Our master explains both the science and Chinese culture,” said Mr. Koh, pointing to the Zhuan Falun, which he gives me an English copy of. “If you want to know about dimensions, then he will explain to you what the dimensions are. The molecular and atomic space. He will explain it all scientifically.”

Over the next week, I take the time to read large portions of the Zhuan Falun, only to conclude that it is in no way scientific—at least not by traditional definitions based on the scientific method. What I did find were principles about qi, karma and pressure points based on a range of ideas borrowed from ancient Chinese culture, traditional Chinese medicine, Taoism and Buddhism.

In Zhuan Falun, all knowledge is synthesized through the experience and teachings of its founder, Li Hongzhi.

The fact that Falun Dafa’s founder is still alive and living in upstate New York, and whose words are a matter of public record online, has only heightened the level of scrutiny that Falun Gong receives from detractors and skeptics.

We’re All Trying to Make Sense of the World

Drawing definitive conclusions on religion is a sensitive exercise, as the very essence of faith runs counter to the idea of demanding evidence of the divine through the performance of miracles.

But if I were to give a personal opinion, it would be as follows:

Falun Dafa, at least in Singapore, is a mostly harmless community that practices qigong and engages in meditation. Its tenets preach an avoidance of extremes and negative emotions, with clear rules against coercion and violence. It has no discernable hierarchy; practitioners do not appear bound by obligations imposed on them from above. Those who volunteer and are active in promoting the cause seem motivated by genuine passion, and a desire to spread its teachings to fellow Singaporeans.

While Singaporeans are free to draw their own conclusions on some of the religion’s more outlandish claims, we also can’t dismiss the benefits that practitioners have experienced as a result of their practice.

Here’s Mr. Koh to speak from his personal experience:

“In my life, I underwent a complete change. Before Falun Gong, I was running my construction business. I was the boss. When I said yes, nobody could say no. That mentality had been instilled in my mind. That’s erased now. I realised I was wrong to think and act that way.

The same thing happened to all my weaknesses. I used to gamble and drink before as a businessman. I do not gamble and drink anymore. When you go into working society, you start to spend more money. And when you really need that money, it’s gone, and you have problems. Falun Gong has taught me how to control myself.

It has taught me how to be a good person while living in this world.”

This post was not sponsored by FLG. RICE would like to thank the Falun Buddha Society for allowing us to gain better insight into FLG and its community.

Looking for your life’s purpose? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.