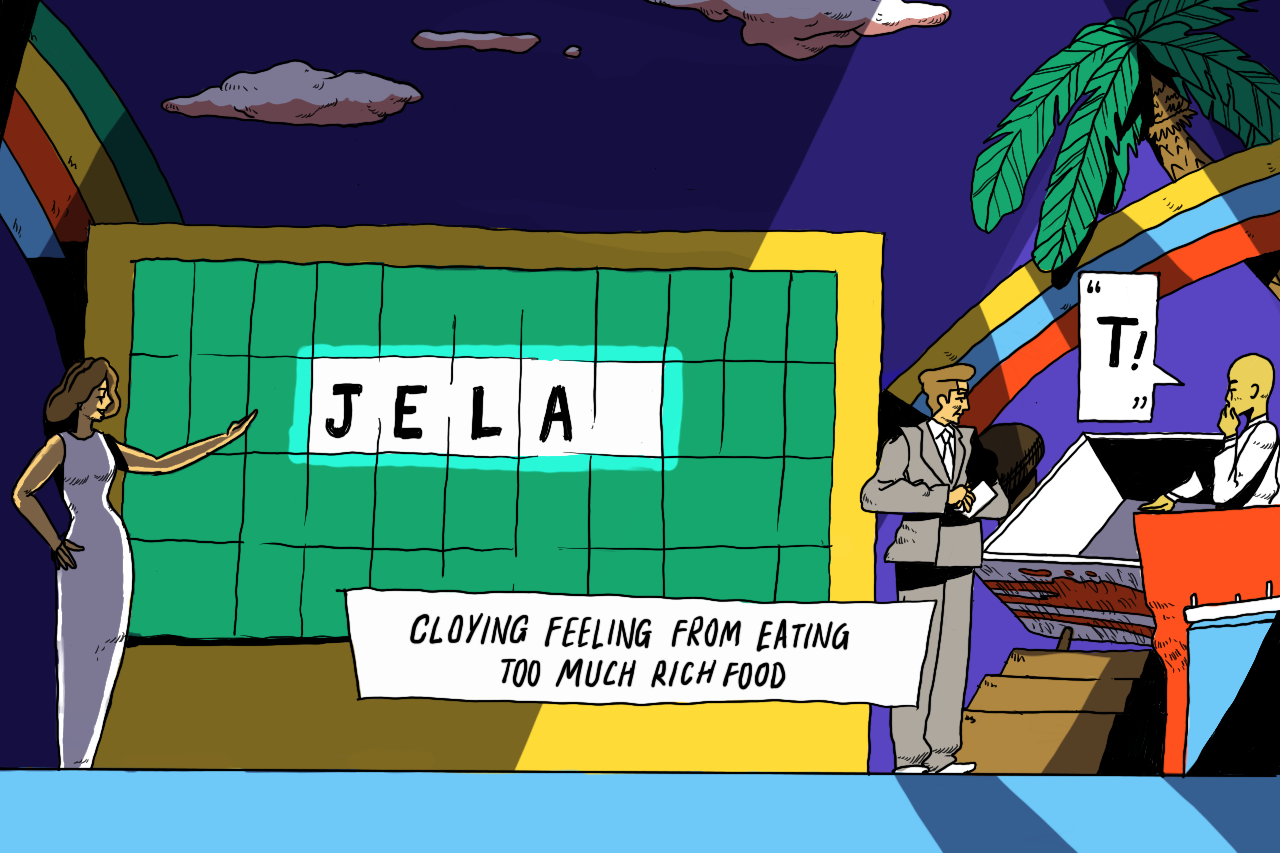

Illustration by Lam Yik Chun.

Over the last two decades of using text messaging, I’ve come to believe that the 10th circle of hell comprises people who use ‘jelak’ without knowing its proper spelling and who continue making the same mistake even after finding out how it’s spelt.

In the Singaporean vernacular, ‘jelak’ refers to feeling ‘sick of eating’ or nauseated, particularly with overwhelmingly rich foods. It’s also so ingrained that any misspelling of the word by a Singaporean is ignorant and inexcusable in 2019.

So please, it’s not ‘jelat’.

Don’t worry, these jelak/jelat offenders won’t be alone. In the same circle of hell, you’ll find people who spell ‘macam’ as ‘machiam’, macam it’s a Chinese word; ‘sekali’ as ‘scully’ a la The X-Files; and ‘mampus’ as ‘mampos’, a monstrosity that’s truly mampus.

Up until a few weeks ago, if you’d thought I was just another damn extra Chinese person feeling offended for a minority race when they never asked for my annoyance, I’d have accepted this perfectly reasonable character assessment.

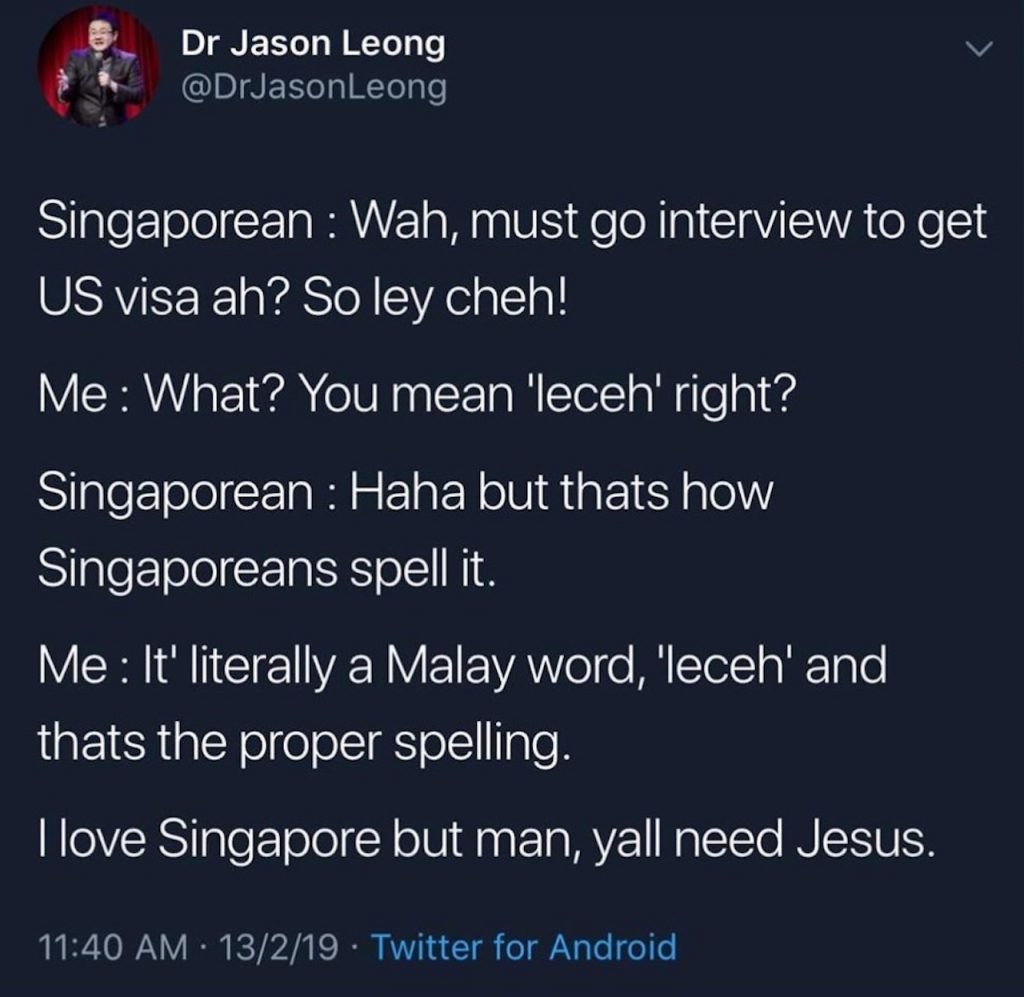

Then this tweet made me realise my frustration with jelak/jelat offenders was a bigger issue that many others could relate to:

Still, I had no clue whether the Malay community or Malay-speaking folk felt the same way I did, although this Reddit thread featuring a list of commonly misspelt Malay words made me believe they might.

I also suspect the race that had the most morons who would frequently misspell Malay words (i.e. mine), but I needed numbers to back up my gut instinct.

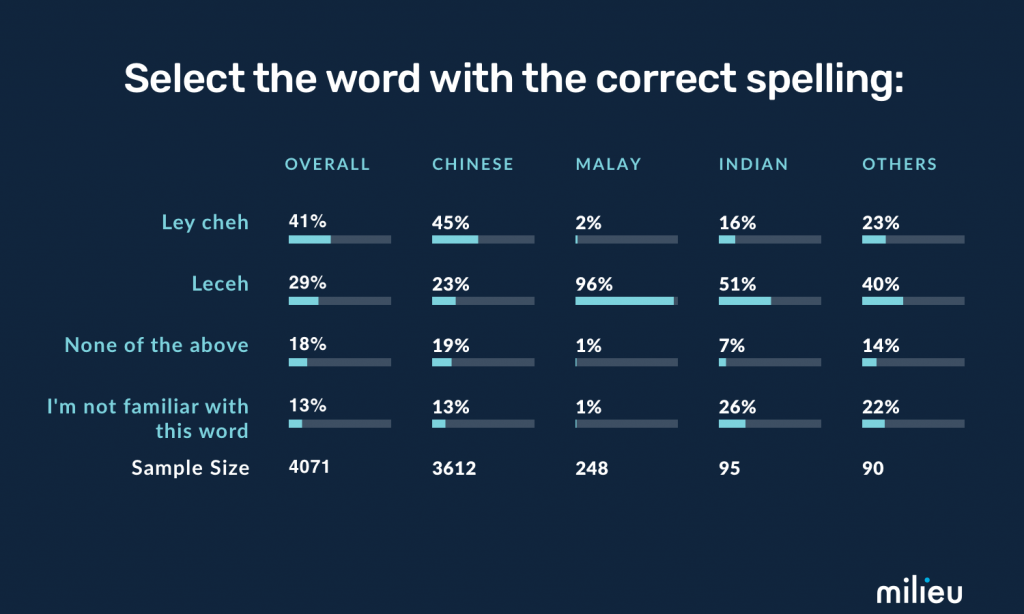

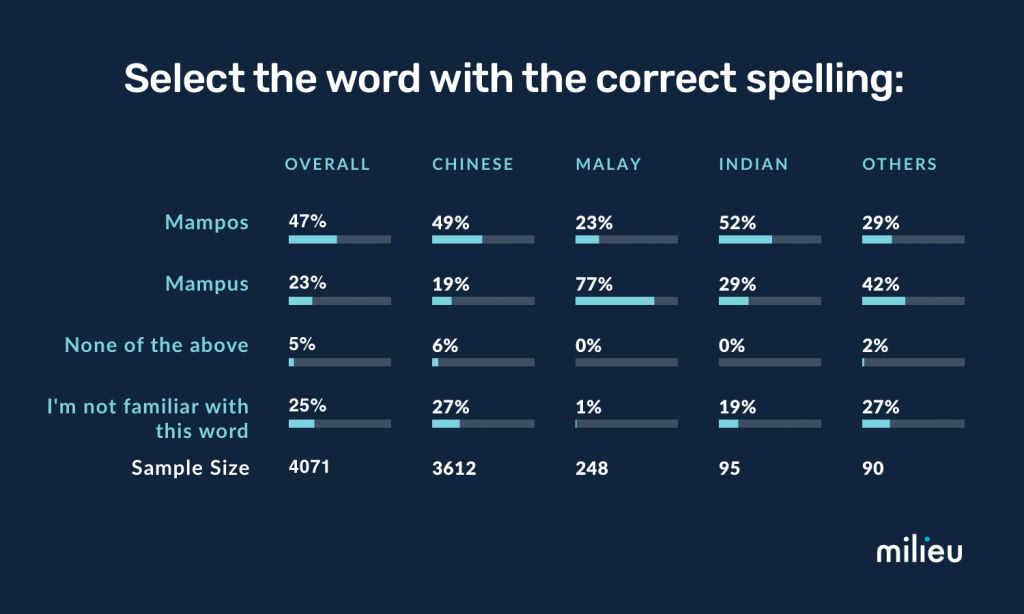

Working with Milieu Insight, we polled 4,071 Singaporeans on how well they could identify commonly misspelt Malay words.

Long story short, I was absolutely right. For every single Malay word polled, the highest amount of Chinese respondents selected the wrong spelling of the word. Which made me feel equal parts validated and appalled.

Bear in mind there were far more Chinese respondents than those from other races (3,612 as compared to 248 Malays, 95 Indians, 26 Eurasians, and 90 Others). To ensure our charts are easier to read, I was advised to remove the ‘Eurasian’ category after seeing the results were negligible.

I also focused on answers specifically from Chinese and Malay respondents for the following analysis because they yielded the most significant differences.

Here are some of the more interesting results:

‘Leceh’ is often used to describe someone or something that is excessively troublesome or tedious. It’s also commonly misspelt as ‘ley cheh’, such as in the aforementioned tweet I shared. In fact, I too had once butchered it that way.

So I wasn’t surprised most Chinese respondents (45 percent) need to repent like me: they thought ‘ley cheh’ was the correct spelling. Interestingly, it was a close fight between the percentage of Chinese respondents who knew ‘leceh’ was correct (23 percent) and those who thought neither spelling was correct (19 percent).

This might be because few people see ‘leceh’ written down. They are usually first exposed to the word via speech, such as when they hear someone complaining.

‘Terbalik’ means ‘inverted’ or ‘upside down’ in Malay. Many Chinese friends are shooketh when they first learn the correct spelling for ‘tombalek’, which is not a word.

There is even a woodworking centre in Singapore called Tombalek, which has gotten flak for using the embarrassing misspelling of the Malay word as its name. Originally started as a guitar-making home project under the same name in 2008, the owner chanced upon ‘tombalek’ and liked how unique the word appeared. When the project became a business in 2015, the name stuck.

Several people assume that Tombalek intentionally co-opts the Malay language by using a ‘catchy and cute’ misspelling to market their services. But they clarify that the name was a purely accidental discovery, and they’re not “silly Chinese people who thought it was fun to misspell the Malay language”.

Similar to leceh/ley cheh, the stark difference between these two spellings might be because most people have the tendency to spell unfamiliar words according to how they sound in the International Phonetic Alphabet. Over time, misspellings endure and get entrenched within our lingua franca due to a general ignorance of their correct spelling and the absence of any willingness to find out.

Unsurprisingly, most Chinese respondents thought ‘tombalek’ was accurate (46%), while 98% of Malay respondents knew ‘terbalik’ was the right option.

‘Macam’ means ‘similar to’ in Malay. With this word, I wanted to test whether people would realise that they were presented with two wrong spellings or if they would feel forced to pick one.

In total, only 10 percent of Chinese respondents selected the correct answer: ‘none of the above’. It’s also good to note that Chinese respondents represented the lowest percentage among the other races.

However, while Malay respondents represented a significantly higher percentage than every other race on the correct answer, they didn’t display heartening results either. Only 60 percent of them selected ‘none of the above’.

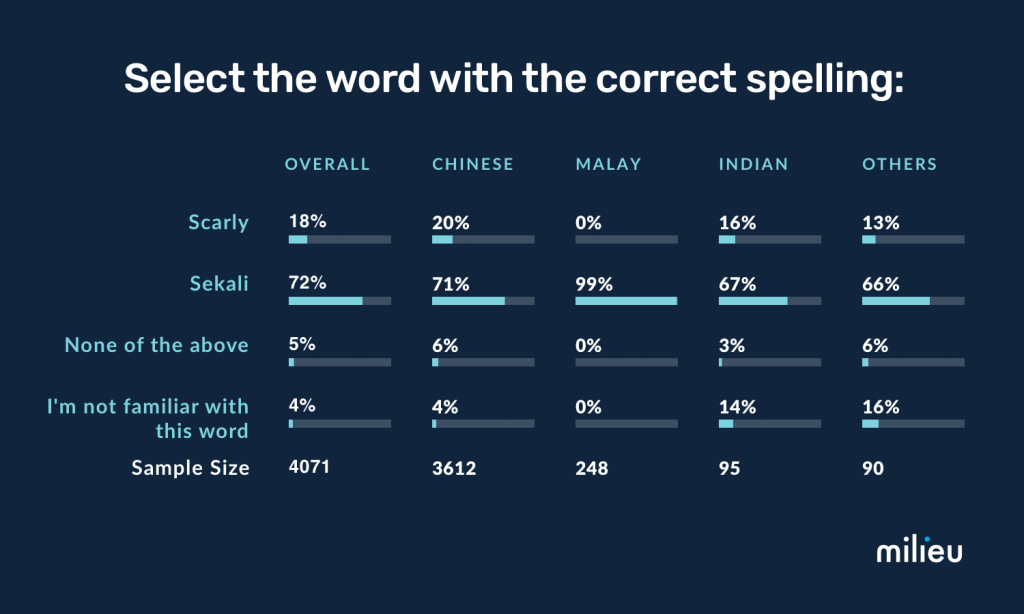

According to Oxford Dictionaries, ‘sekali’ means ‘once’ or ‘on one occasion only’. But in the Singlish context, it implies the same meaning as ‘lest’ or ‘what if’.

It was heartening to realise most Chinese respondents (71 percent) knew the correct spelling of the word. But I couldn’t help wondering if it was only because the misspelling I’d used in the options was ‘scarly’, which is rarely seen.

Perhaps this percentage wouldn’t be as high if the misspelling was ‘scully’—a more common version. Or perhaps I should simply have more faith in my fellow privileged brethren.

In Malay, ‘mampus’ literally means ‘dead’. In Singlish, however, it’s an expression that someone or something is a lost cause; mampus means ‘gone case’ or ‘si liao’. (The latter translates to ‘die already’.)

Surprisingly, even though most Malay respondents knew the correct spelling was ‘mampus’, this percentage was only 77%. This is relatively low compared to the rest of the commonly misspelt Malay words, except for ‘macam’, which had over 90% of Malay respondents selecting the correct answer.

If anything, it reflects the idea that language is a living object. Its rules often change according to how people use it, including adapting to the bastardised spelling of a word.

As expected, most Chinese respondents (53 percent) thought ‘jelat’ was the correct spelling, while only 17 percent of Chinese respondents knew that ‘jelak’ was accurate. In comparison, 94 percent of Malay respondents knew ‘jelak’ was the correct word.

But what I really wanted to know was who the hell were the 4 percent of Malay respondents who thought ‘jelat’ was correct, as well as the 2 percent who were unfamiliar with the word.

DISHONOUR ON YOUR COW.

But numbers alone don’t paint an accurate picture of the broader frustration of seeing words in your language consistently misspelt.

My friend Fatimah was the one who shared that original tweet. In her post, she also added a few more Malay words that she noticed were commonly misspelt: kachiao/kajiao (correct spelling: kacau), ah bang (correct spelling: abang), and kantang (correct spelling: kentang).

“I had some Malay-speaking friends who ironically misspelt those words since I shared the tweet. To me, that kinda reaffirms that intentional misspellings may be a commiseration of our shared experiences,” she says.

But finding solidarity doesn’t mean it’s acceptable to misspell another ethnic group’s language, especially if you don’t use it.

Fatimah explains. “It feels like an annoying younger cousin messing up something you like. You’d just shake your head and go, ‘Sigh, cute try lah.’ But then you both grow older and you expect them to grow up and stop making messes too.”

Likewise, Nadia (not her real name), who sometimes posts IG Stories of misspelt Malay words, says she’s totally cool with people who acknowledge and move on from their mistakes. It’s those who stubbornly refuse to use the correct spelling who get on her nerves.

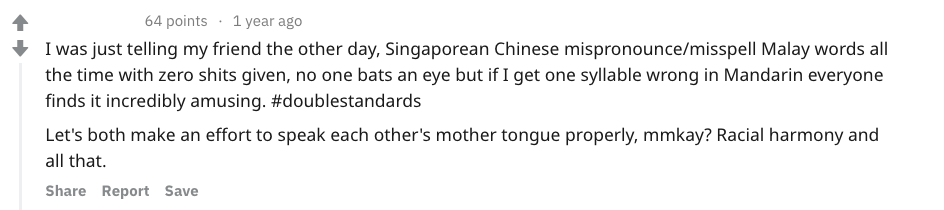

It didn’t help that people used to laugh at Nadia’s mispronounced Mandarin when she was growing up. Having other people constantly belittle her didn’t provide a comfortable environment to learn a new language without feeling bad about making mistakes.

“For example, I would mispronounce ‘liang ke’. Then someone would snort and go, ‘Hahahaha it’s not lee-ang KE, it’s liang GE’, and everyone else would also laugh. It’s like they couldn’t fathom that I couldn’t pronounce a simple Mandarin word,” she shares.

Thankfully she has since found “quite woke” Chinese friends who are open to her correcting their misspellings, just like she’s open to them correcting her misuse of Mandarin.

That said, cultivating the kind of culture that Nadia has been lucky enough to find among her friends isn’t an overnight task. One may realise it’s pointless getting upset because there’s no harm meant in the misspellings. After all, choosing words from different languages and adapting them over time is part of Singlish.

At least, that is what another friend, Sirhan, believes. He once posted an IG Story of an article on our site, where our writer spelt ‘jelak’ correctly. His half-joking caption was full of disbelief: “Omg this Chinese person just spelt ‘jelak’ correctly.”

He is also resigned to the “indifference” from others and “empathy” required of himself, which he treats as “part of the minority experience”.

“I mean, the fella already attempting to use my language in his speech, so must give chance lah. Not like he hate Malays or what. Chinese people misspell Malay words, Malay no need to be angry. Just spell correctly when you use it on them and hope they remember,” he says.

Occasionally, his Malay friends go along with the misspelt Malay word if Chinese people are in the group chat. So he feels proud when his Chinese friends do learn from their mistakes after he corrects them because “it shows they give a shit about something as ‘small’ as this”.

“Something I noticed among the folks I know is that those who tend to misspell in a very bad way tend to come from schools with generally very few or no Malays,” he adds.

“Damn poor thing, but it also shows how our society still isn’t as inclusive as we think.”

Ah, inclusivity. The trendy catch-all word has come to denote progressive ideologies we wish to possess. Yet it doesn’t encompass the tedious work, especially from the privileged majority, that it takes to materialise this idealism.

Unlike her Singaporean Chinese counterparts, Low Zoey, who’s Malaysian Chinese, has a relationship to Bahasa Melayu tied to her nationality and has studied the language formally for many years in Malaysia. So she has seemingly stronger views than many others I speak to.

“I don’t expect people to be flawless linguistic maestros. However, what I find lacking is empathy for smaller cultural and linguistic groups, a curiosity to learn more about them, and the emotional intelligence to listen and dignify their input and lived experiences,” she says.

“How do you think Malay speakers feel when they have to see or hear their language being repeatedly, and sometimes deliberately, butchered? And on top of that, they’re told that there’s nothing wrong with it.”

If it’s hard to empathise, just imagine constantly getting your name spelt wrongly, despite the other party knowing its correct spelling. It’s aggravating, insulting, and it’d make you feel small, to say the least.

By deliberately continuing to misspell or mispronounce these words, Zoey explains that people don’t just indirectly dismiss the Malay language and culture but also demonstrate that their own comfort and familiarity are more important than learning from other cultures.

She also refuses to pander to the common response—“This is Singlish”—for every instance she points out a misspelt Malay word.

Even though Singlish is a creole language, she objects that “certain dominant social groups sanction these misspellings as hallmarks of Singlish when there are other minority voices that are speaking up to correct this mangling of their native tongue”.

So this is what inclusivity looks like. For Chinese people, it’s not just about being aware of how our privilege as the majority race influences how we’ve been misspelling Malay words. It’s also about making a concerted effort to correct ourselves and others when chances arise.

To do that, we must forge comfortable relationships that allow everyone to admit to and learn from mistakes openly. This will also enable us to embrace a greater range of correctly spelt words from other minority languages in Singlish without fear of fucking up.

Otherwise, you may be well aware that ‘sekali’ is not ‘scully’ and ‘macam’ is not ‘machiam’. But until you know why you should spell these words correctly, you’d continue to revert to their misspellings out of familiarity, stubbornness, and plain idiocy.

That one really mampus.

Milieu Insight is an independent market research company that measures public opinion through a mobile survey app. The survey was conducted between 27 Feb 2019 and 8 March 2019 with a sample size of n=4071 respondents based in Singapore aged from 16 and above. The responses are weighted to represent the online population of Singapore.

You may definitely tell us off if our Chinese writer made any mistakes with this piece: community@ricemedia.co.