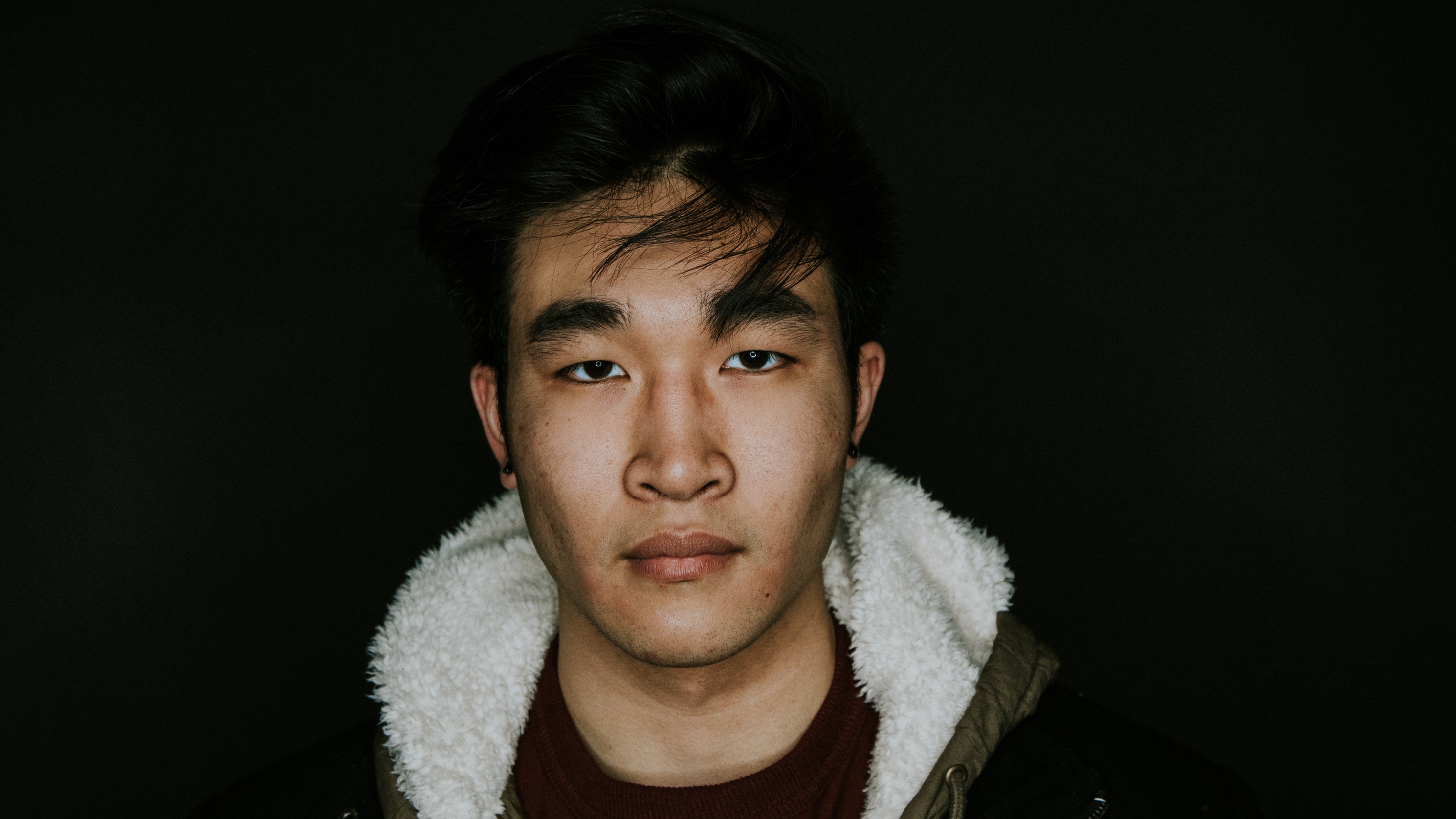

And so I invited Wei Jie, a friend from poly, with whom I had first discovered the joy of playing poker. It had been years since we met, and I was looking forward to catching up with an old friend.

I was chilling in my room with everyone else who had arrived when someone opened the door and exclaimed, “Eh bro! Desmond is here!”

“Who the hell is Desmond?” I retorted, bemused.

As it turned out, it was none other than Wei Jie, who was now introducing himself to his new friends as ‘Desmond’ instead of ‘Wei Jie’, the name he was given by his parents.

I have to admit, I was rather put off by Wei Jie’s personal rebranding. It felt as though he was ashamed of sounding like the atypical “Singaporean Chinese” male who went to a semi-decent Chinese-speaking secondary school and spent his formative years sipping on bubble tea at the neighbourhood basketball court.

Of course, this was not the first time I’d come across an incident like this. I’ve known people who drop their Chinese names entirely, going solely by their surnames, like my colleague who introduces himself as Toke instead of Hong Loong. An acquaintance I know goes by ‘Kai’ instead of ‘Kai Qiang’.

I started questioning the reasons why people choose to desert their given Chinese names, and to see if there are deeper reasons behind it aside from what one might assume to be shame.

And as it turns out, there are.

A friend who works in an MNC tells me why.

“I feel that having an unpronounceable name can be disadvantageous in a professional setting because others might not be able to remember your name, and this might affect the opportunities you have at work,” said Shun Ze, who introduces himself as Albert in the office.

Apparently, this phenomenon has been occurring for decades. Choon Guat, a retired housewife who worked in several establishments situated in town back in the 70s and 80s, had to use a Christian name, Lilian.

“I worked in Metro, so there were quite a lot of foreigners. My boss was also caucasian so it made things a lot easier to have a Christian name,” said Choon Guat.

“I also didn’t like how Choon Guat sounded, it was Hokkien and sounded like a boy’s name. Lilian sounded much nicer.”

And when Singaporean Chinese folks are honestly not that Chinese anymore, is it still fair to judge them for adopting English or English sounding names? Perhaps not.

We watch American sitcoms on Netflix and scoff when we see ads for original content on Toggle. Increasingly, we scour the web for food blogs like SethLui and Makansutra to find out where we can find the best brunches, just so we can avoid going to the hawker centre at the wet market for a chwee kueh breakfast.

When I still played FIFA ‘05 on the PlayStation, I spent as much time attempting to imitate the British accents of the commentators as I did blaming lag for a loss against an opponent. Needless to say, the Speak Mandarin campaign fronted by JJ Lin and Hossan Leong that same year fell on deaf ears.

This could be why we are constantly seeing efforts by the government or other organisations to “reclaim” our culture, which is alarming when you consider the relatively young age of our nation.

Even for someone like Shun Ze who feels proud to be Chinese, he readily admits that aside from conversing with his parents in Mandarin and celebrating festive events, being Chinese has no real bearing on who he is and what he does on a day-to-day basis.

“I consume large amounts of western media because I prefer it, and the education system has moulded us to be more western-centric to be more competitive in the English speaking world,” he tells me.

Perhaps, it was LKY’s orders to make learning English compulsory for every Singaporean child back in 1965 that was the beginning of this slippery slope. While the results have been rewarding, and we’ve undoubtedly jumped “from third world to first” in a matter of decades, I can’t help but feel that Singapore’s Chinese culture has been irrevocably eroded.

Unlike the Malay community, where race and religion are so entwined, the only thing holding Chinese people to each other and their culture has been their race. We don’t gather together every Friday afternoon for prayers, we don’t fast collectively and start eating together at the same second every day for a month. All we do to celebrate our Chinese-ness is to buy marked-up rice dumplings and mooncakes once a year and eat them in our homes. The only other time is the Lunar New Year, which is usually only spent with our immediate families.

Being Chinese is being the kiasu auntie who chopes tables at Lau Pa Sat. Being Chinese is being the uncle who chugs ABC stout at a coffeeshop on a warm afternoon. Being Chinese is being the Ah Beng who frequents siam dius with the sole intention of “chionging”.

Most of all, being Chinese is inconvenient. Being Chinese means waking up at 2am and driving on dirt paths in Choa Chu Kang to sweep the tombs of ancestors on Qing Ming. Being Chinese means standing next to a furnace and burning thousands of paper offerings, leaving you smelling like a chimney for the next few hours.

Thinking back, while she probably did so to ensure that we would have an easier time during her funeral, I cannot help but wonder if it is these little adjustments and compromises we make that pave the way for our Chinese-ness to dwindle.

Considering that none of this is really avoidable due to the melting pot culture that defines sunny, globalised Singapore, being Chinese is no longer central to our identities any more.

We might be Chinese, but we identify as Singaporean, which is to say that we also identify as doctors, bankers, writers, mechanics, business owners. It has become nothing more than a category we’re shelved into on our NRICs.