Photography by Liang Jin Tey.

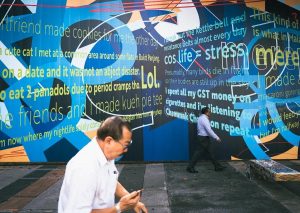

You recognise this too, I’m sure. It’s been more than a year since life has felt bleh, a state of being sian in a limbo of stagnation and emptiness. Your senses and your motivations aren’t as sharp anymore, dulled by the lack of separation between work and life. When you’re literally waking up in your office, it’s hard to switch off.

I, for one, loved the circuit breaker (please don’t @ me). Perhaps it’s the fact that commuting is a bitch, perhaps it’s the inner misanthrope, but I found those quiet months at home the most productive I’ve been in years. No meetings-that-could-have-been-emails, no lets-get-lunch-somewhere-together, no shit-I-missed-the-bus-so-it’s-going-to-be-a-half-hour-wait (I worked in a distant black hole in industrial Bukit Merah back then). There was time to start exercising, there was time for siestas, there was time to fit in a quick game or two in Modern Warfare.

Understandably, not everyone feels the same about this flexibility. When the lines between the home and the workplaces are blurred, in comes a grim sense that work doesn’t really end.

We’ve come to realise that we don’t need actual offices to do our jobs. But on the flip side, we’re unconsciously punching in more hours as Slack and Zoom form the background and foreground of our lives. Last year, the National University Health System’s (NUHS) Mind Science Centre found that 61 per cent of those working from home reported feeling stressed.

By the time we’re having nightmares about emails that don’t find you well and imposter syndrome-related breakdowns in our bedrooms, it’s already too late — we’re burnt out.

Now, colleagues smarter than I am have already articulated the issue of work burnout better than I can. One piece called for Singaporeans to acknowledge that positive change in work-life balance comes from within; that managing our own expectations (about workload limitations and job identity) and the expectations of others (colleagues, employers, clients) is key.

Another piece argued that burnout culture primarily stems from the organisational structures and practices adopted by workplaces and industries.

Both articles portray the normalisation of deviance: a phenomenon when people within an organisation become so insensitive to deviant practice that it no longer feels problematic. Coined by sociologist Diane Vaughan about NASA’s disregard of a dangerous design flaw that led to the Challenger space shuttle disaster in ’86, I’d say that the acceptance of long-held awful workplace customs (be it the individual or the organisation) results in a crash-and-burn sitch as well.

But is there a place in the conversation to talk about how our actual workplaces play a part in burnout culture too?

Hybrid Office, Hybrid Theory

Someday—which is not arriving anytime soon, by the state of things—the world will eventually return to a larger degree of normal and we can start escaping to Bali (and not just Bali Lane) once again when we’re worn out from work. In its wake, however, is the absolute knowledge that things won’t be the same, especially in the way we work in the office.

“I would confidently say: never,” laughed Narita Cheah when I asked her if the status quo for workplaces will ever return in the post-pandemic.

“No one actually questioned offices in the past—you didn’t have a right to. And you accepted it because you had no choice,” said the 45-year-old co-founder and director of regional workplace design collective Paperspace Asia.

“The pandemic has revealed to people that they do have a choice in terms of an alternative: remote work—whether it’s at home, a cafe, or a library space. They realised that they had a choice outside that assigned seat in the office.”

When Paperspace established themselves four years ago—well before any inkling of Covid-19—the founders had already identified a shift in the way offices of the future needed to be designed.

Depending on their clients’ needs, Paperspace consultants would then use spatial design that would be fully optimised to support the organisation’s goals and flexible enough to change behaviours and help achieve these outcomes. An IT consulting company, for example, would require things like movable office furniture and modular rooms, as opposed to a tropical-themed hotel that required aesthetic warmth and luxurious appeal.

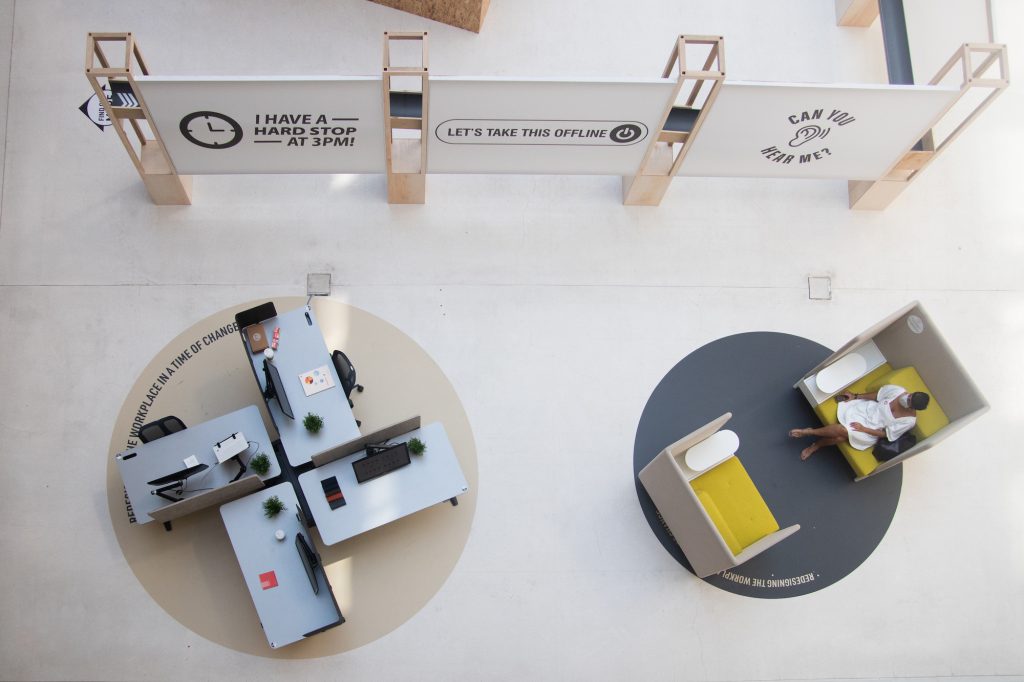

More recently, Paperspace launched its HybridWork Lab experience—an open space on the third floor of the National Design Centre for anyone to try out its brand of people-driven workplace strategies and flexible office design. A solid conference table sits outside the Paperwork co-working space for people to work by themselves or facilitate team discussions, accompanied by whiteboards (both digital and analog) for general presentations or quick brainstorms.

Narita believes that the office has been disrupted, yes, but the office is here to stay. Its fundamental purpose, however, will look radically different in a future where remote work is increasingly adopted. The hours needed to be spent physically in the office will change, but it’s for those hours that Paperspace wants to create an optimal environment. This is where the concept of hybrid working comes into play.

Narita ponders on its definition for a moment.

“I think hybrid working is about having the freedom to choose where you do your most effective work — individually and as a team.”

The model proposed offers workplace flexibility that fits according to the task needed to be done. Some people (like myself) thrive on working in solitude, delivering our best work away from office spaces. Others do well working intermittently, peppering their work hours with frequent short spans away from screens and keyboards. There are also the ones that need to feed off social energy, requiring face-time with colleagues to get things done quicker.

Not recognising the different quirks and work philosophy of individuals, i.e. shoehorning them into a strictly traditional office space and culture, contributes to burnout.

“If anything (in the aftermath of the pandemic), we tell organisations that employees have realised how important their health is—more than their jobs,” offered Narita.

“The companies that know this, and start to not just provide facilities and amenities around it, but talk about it, create safe spaces… in that sense, support their team to regularise expectations about work, would have their employees on for the long run”.

Paperwork at Work

The Herman Miller Sayl chair is ergonomic engineering on steroids. Its backrest is rubberised mesh—curved, bendy and perforated just right to give your back an airy, comforting hug, like a Sufjan Stevens song. The seat foam is thick enough but not too much to feel like you’re drowning in cushion. Through the mysterious machinations of adjusting levers and knobs, I found the sweet spot for the office chair’s seat depth (I’ve got long legs) and tilt (I like to lean back).

Normally, the science of ergonomic furniture wouldn’t have to occupy space in my head. But here I am in 2021, a year on since traditional office arrangements have crumbled, figuring out if I should spend nearly $1,600 on a Herman Miller Aeron. I mean, if the lines between office and home are getting blurrier each passing second since the pandemic, might as well get comfy.

Fortunately for my wallet, I didn’t have to spend a third of my monthly salary on an office chair. Paperwork, the creative co-working space under Paperspace, had more than enough of the Sayls to go around.

After a week-long stint spent at Paperwork, one Rice colleague agreed. “We tend to overlook the physical impact the chairs we work in have on our posture and overall health I guess,” she said.

But hybrid working is more than just fancy furniture, Paperspace affirmed. Even though having height-adjustable desks that can double as whiteboards to scribble on is pretty nifty.

The design philosophy of a nimble, purposeful workspace permeates Paperwork. Just past the entrance holds the pantry and lounge area, where high external traffic allows for convenient networking, collaboration and banter (the free coffee and snacks help). The fully-decked out meeting rooms are modular, and the walls can slide away to create larger spaces to host conferences, events and parties.

Those seeking quiet refuge can enter the little nooks, booths and pods to take quick calls or just get into the zone. A hammock for napping can be found in an outdoor balcony, though nobody really used it for a quick snooze or chill sesh during the time we were using the space. Does anyone really want to be caught sleeping on the job?

The key takeaway from the design language here is that every arrangement of furnishings and amenities has a purpose, with logic and fluidity to work at different spots.

If you want to focus and churn, hit a quiet semi-soundproof nook. If you need to hold a 10-minute discussion with colleagues, call them over to a standing desk nearby to spitball ideas. If you need a break, the warm, inviting lounge is right there.

Most importantly, you don’t even need to work in the office; you could always find somewhere else or even head back home and resume later on. High workload volume, monotony, unclear job expectations, work-life imbalance; all contribute to burnout. But being able to control and influence where and how you get the task done—that’s a big step towards giving it a wide berth.

Co-workers at Rice agreed that having the freedom to operating across a variety of spots in the hybrid office does have a refreshing effect, a way to tackle the mundane elements of work and falling into a monotonous routine. Hybrid working, then, speaks strongly to the people who prefer or even need to have the freedom to operate in a combination of remote and in-office setups.

Think those with dependent family members, mentioned a colleague. Such a model allows them to juggle various commitments in lieu of making the binary choice of going to work or forsaking their career.

I’ve spent close to a decade working in various places where I was expected to clock in on time, plop myself down at my desk and barely move anywhere else lest I miss the latest Viral Thing On Facebook to churn out some paltry bullroar that passes for news content these days. The relentless chase for views has always been the main source of fatigue—there’re only so many times you can write about otters until you get sick of the slick little runts.

Barring the clickbait churn, burnout might have been alleviated if presenteeism wasn’t such a prevalent practice here. I probably wouldn’t have started calling it in for every single one of my articles if I was offered the freedom to split my time between working in the office and working remotely. Or at the very least, have the fluidity to operate in conducive spaces.

During the week-long stint at Paperwork, a community manager was visibly concerned as she made a beeline for the exit, asking why I was staying behind past 7pm.

“Maybe it’s a habit from hustling in startups. You know, first in last out sorta thing.”

In truth, I didn’t really know the answer—I could certainly call it a day but I didn’t want to. Perhaps it really is a habit from the years of traditional office hours. What’s for certain is that the culture of overworking and overcompensating wouldn’t be such an ingrained attribute if hybrid working is the norm.

It was in spaces like Paperwork that the light shone a little brighter. Watching community managers chat with tenants over drinks at the lounge while my Rice colleagues hold serious sidebars over politics at the standing tables, it’s obvious that everything was designed to inculcate an acceptance to be flexible in work and in using workspaces.

Granted, the Rice team has progressively adopted this hybrid working model, but it was in Paperwork that we realised its full potential. It’s this potent union of freedom, seamless space, and the sense of community support that you can’t find in the offices of yore.

Really, there shouldn’t be any pride in staying rooted behind a desk for over 8 hours a day. Narita believes that the time is nigh to do away with this mindset among companies, especially when hybrid working will constitute what’s normal for the foreseeable future.

“Some employees have performed incredibly well in the remote environment and will want to continue working this way. On the other spectrum, there are those who can’t and need to be in the office because they’re most productive there,” she remarked.

“But probably 70 to 80 per cent of us sit right in the middle, where I do want to come back (to the office), but on my own terms.”

This, she quips, is the office of the future.

This story is published in partnership with Paperspace and Paperwork.

Stay updated with RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.

Send us your ideal workplace model (and don’t you dare say you’d rather not work at all) over at community@ricemedia.co.