Sponsored content. The scourge invading social media feeds everywhere.

When I last wrote about the homogenous state of Singapore’s YouTube scene, my interviewees wouldn’t shut up about the disdain they had for influencers as vehicles for advertising. And you, our readers, are no different, never missing an opportunity to let us know how much you don’t appreciate our efforts to put food on the table.

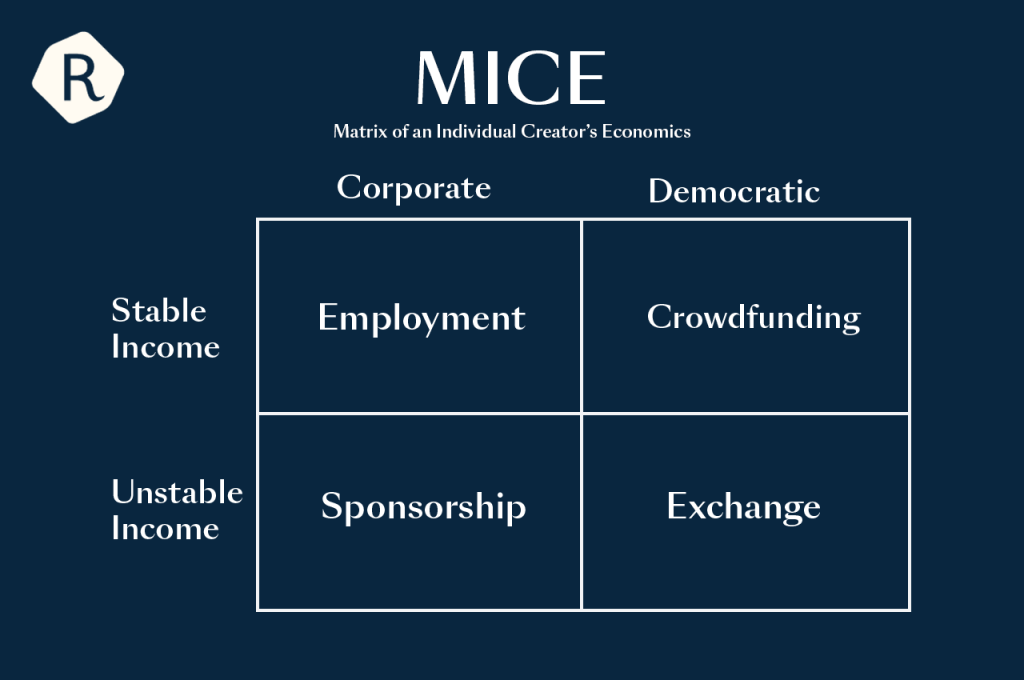

After hours of rigorous research, RICE has come up with a newly patented table to break down the avenues of income available to content creators—and their implications.

2. Sponsorship: Quid pro quo with corporate stakeholders—you advertise, they pay.

3. Exchange: You hustle with products behind a paywall, or a subscription model, or goods/services you exchange with customers for money.

4. Crowdfunding: Most of your content is free, and your audience pays to support you.

Content creators who subsist from the left column get more flak than the right because they have less control over their work—and can be seen as less genuine/authentic.

As an employee I’m allowed to traipse around Sentosa Cove like a buffoon and write about my favourite hobby, but the final published piece is ultimately subject to RICE’s editorial process. It’s for a good reason: editors help to refine pieces, and a good media company will serve their audiences’ needs first. The best works are borne of collaboration.

But corporate oversight generally still triumphs. For example, the New Yorker is famous for having a strict style editor, which my own editor loathes because it makes otherwise interesting profiles and features sound bland.

Plus with the recent firings and walkout of writers and editors at sports journalism website Deadspin, there’s little doubt that bosses get the final say when it comes to your paycheck.

Creating content for external brands is perceived as an even greater sin. Again, sponsored content can be well-executed if the brands and content creators align in their values. But what if they don’t? It’s easy to preach the moral high ground when your livelihood isn’t at stake, but content creators often have to resort to branded work in order to fund their passion projects.

So if the left column is full of miserable compromise, why aren’t content creators going to the flipside? What’s stopping audiences from paying their creators?

And in the Internet era, most of this content is digital, and free.

Like the printing press and radio before it, the Internet has revolutionised the media. Without the constraints of physical matter, creators and audience have virtually unhindered access to each other.

This is inarguably a great boon. Educational resources like Crash Course and Khan Academy have benefitted millions across the globe, allowing anyone with an Internet connection access to high quality education—not to mention the thousands of content initiatives that have enriched lives across the globe.

So since the 2000s, platforms like Livejournal, Fanfiction.net, Archive of our Own, Wattpad, Deviantart, Tumblr, Twitter, YouTube and even Vine TikTok served as proving grounds connecting creators to their audiences. In particular, online fandoms have helped cultivate passionate communities of adolescents eager to create content before any monetisation mechanism was in place.

But as amateurs honed their skills and people realised they could make a living out of their hobbies, the damage was done.

It’s easy to build an online following when you’re giving out free content, but when you set that precedent it’s difficult to transit to making money.

— Wei Choon from The Woke Salaryman.

In economics, there are two theories of value worth examining to highlight why the content creation industry is where it is—stick with me I promise it’ll be interesting.

Put simplistically, the labour theory of value states that when a person takes raw materials, uses their labour and expertise, and transforms it into a good or service, it is that labour and expertise which gives the product value.

Whereas, marginalism claims that value is bestowed only when a consumer buys a product, based on how much marginal utility they can gain from that product.

In some sense both of these are true in our see-saw of demand and supply. But let’s paint a picture:

Most people create digital content for free—look towards any social media platform—and thus, online content is consumed for free. You’re able to get unlimited amount of utility without having to pay a single cent.

On the other hand, the amount of labour—and resources—going into content creation is immense, not to mention the years of training needed to gain expertise. This piece alone has taken three months of intermittent research, sourcing for leads, interviews, transcriptions, and that’s before I start writing.

Even if I was paid $10/hr, this piece would easily rack up $300 in costs.

There’s a huge disconnect between audiences’ perceived value of content, and the amount of labour that goes into creating it. So, if audiences aren’t willing to pay creators because they don’t see the value of content, who does?

Advertisers.

In the past, you could just slap on native ads next to content, but plugins like AdBlock have made these methods much less effective.

But if the ad is baked into the content itself, you can’t skip or block them. And if the content is good, most audiences will begrudgingly accept the tradeoff.

Yet we wonder why sponsored content is so ubiquitous.

Rachel, you’ll just have to accept that you’ll be poor.

From the age of 8, Rachel Pang was constantly told that being an artist was not a viable career option in Singapore. But when she went to college in the US, she saw her peers putting themselves out there as artists, even those without professional training.

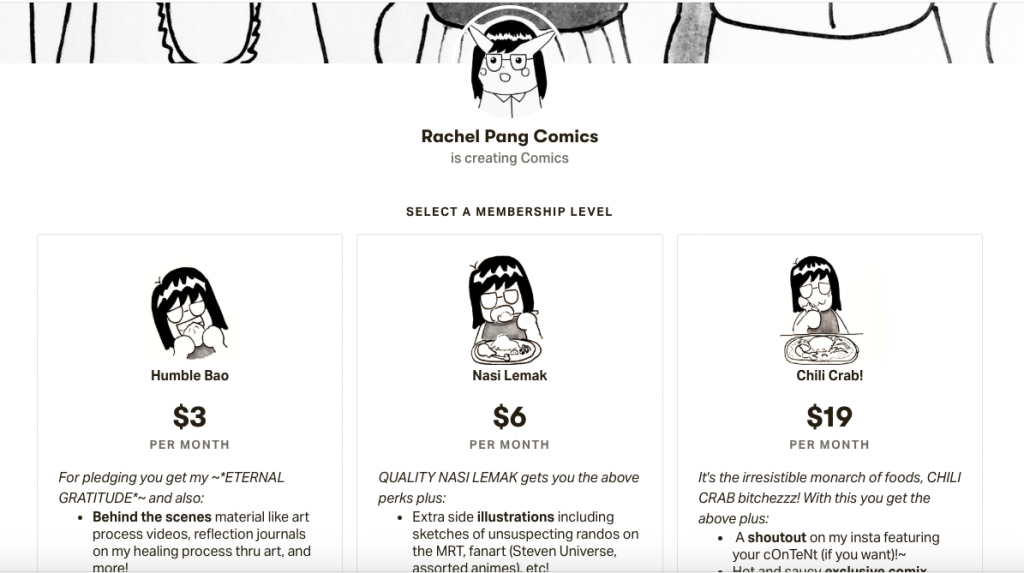

She decided to pick up the pencil herself in her third year, and created an Instagram account in October 2018. Since then, Rachel Pang Comics has grown to 8,000 followers.

Rachel juggles her art alongside her full-time job, and keeps up with her art by recognising its importance to her, and prioritising it. She recalls late Monday nights after work spent drawing, staying disciplined to get in the practice she needs to improve her craft.

While she’s glad her full time job allows her unrestricted artistic freedom to discuss topics like LGBTQ and mental health issues—which sponsors tend to stay away from—she hopes to eventually transition into becoming a professional artist.

But garnering financial support has been difficult. For one, there are the complaints regarding commission prices, and Rachel finds many people often asking her when she’s publishing a book—but offering nothing else to support her finances in the interim.

“It’s like, ‘I like you as a comic artist, but if there’s no physical product there’s nothing I can support you with’,” Rachel sighs.

Even as the print industry croaks its swan song, many are only willing to pay for something they can touch. Some publications still focus on print, like Mynah Mag. Their success in funding three issues speaks for itself.

Ruby Thiagarajan, Mynah’s editor-in-chief, writes that “it would be much harder to raise funds if we were just online. All money from the preorders goes back into the magazine and, vitally, towards ensuring that we can keep publishing.”

Despite digital content being more convenient and less pricey, if you want to make a living through the “exchange” quadrant of MICE, you have to go offline. But in order to gain a following in the first place, you have to consistently put out free content, competing with millions for audiences’ attention.

And looking at MICE, hustling to sell your goods and services is dependent on your performance, and the income generated is unstable. Such are the woes of entrepreneurship.

It’s a juggling act that would leave anyone burnt out faster than climate change.

For the uninitiated, Patreon is a crowdfunding platform for audiences to support artists through small, monthly payments. Remember, what differentiates our definitions of ‘crowdfunding’ from ‘exchange’ is that in the former, one’s online content remains free, even if there might be perks for supporters: your name in the credits, direct communication to creators, or the ability to influence future content.

It’s currently the best way for online content creators to subsist with a stable revenue while churning out free content, without working for corporations.

So you’d think once creators have paid their dues to cultivate a large audience, money would soon follow, right?

Enter Peggie Neo, a Singaporean YouTuber with over 900,000 subscribers, and tens of thousands of views on her almost daily mukbang videos, amounting to a total of over 150 million views. She has a secondary drawing channel with 25,000 subscribers, and … 5 patrons.

It’s not like she doesn’t plug it—the links are as clear as day in all of her videos. She could probably subsist off her videos’ sweet ad revenue, but the disparity between followers and those willing to pay her is staggering.

Even SG YouTube heavyweight Night Owl Cinematics’ Patreon barely earns enough to provide pocket money for a schoolkid. What hope do independent content creators with smaller audiences have?

For instance, Rachel only has 19 patrons—of which 12 are friends, 3 are partners of friends, and 2 are foreigners, leaving only 3 Singaporean strangers. Most Singapore Patreons are doing so poorly that you’d earn more waiting tables for a day than they would in an entire month.

Contrast this with the big names of Patreon around the world. The best performing Patreon—left-wing podcast Chapo Trap House—rakes in over $140,000 USD per month. YouTubers like Contrapoints and Lindsay Ellis earn enough to comfortably hire small teams, and even my favourite niche webserial author, Wildbow, has a respectable monthly income of $5,894.

Content is free around the world, so what gives, Singapore?

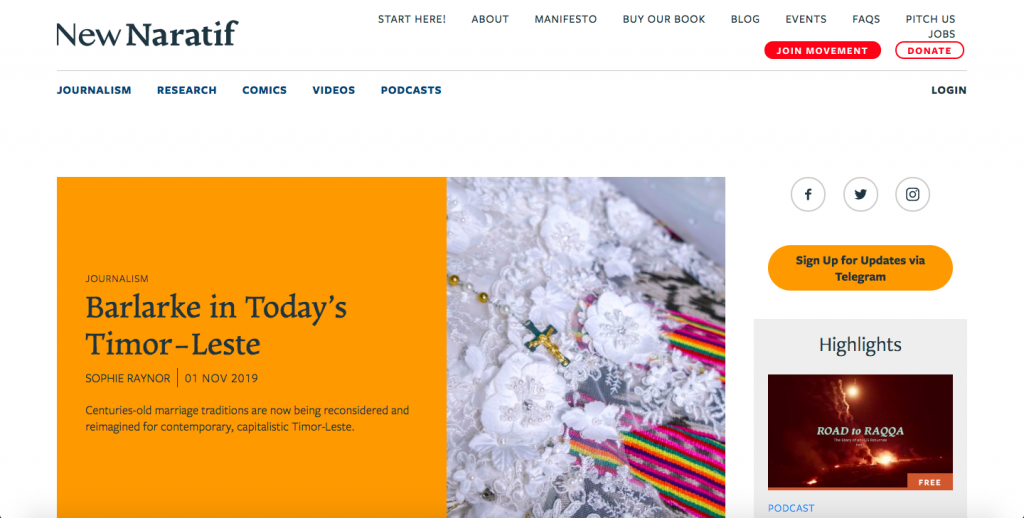

It’s still a far cry from their goal—they’re aiming for a minimum of 2,200 members, with 7,200 being ideal.

Kirsten Han, NN’s editor-in-chief tells me that Singaporeans grossly undervaluing content is due to them not understanding the sheer amount of work going into it. Besides the various stages of the journalistic process I highlighted above, New Naratif struggles to afford travel expenses for journalists, since their work covers SEA and some stories require groundwork spanning the region.

This is a sentiment Wei Choon from The Woke Salaryman—a comic about financial literacy—agrees with. He suggests creators should show behind-the-scenes content so that audiences can understand the amount of effort going into the craft.

But as Kirsten explains, it’s useless if everyone ’theoretically’ agrees such content is important and valuable, but no one puts their money where their mouth is. While content creators must keep their work accessible and responsive to their audiences, people have to meet them halfway.

Rachel posits that it depends on the demographics of one’s audience—her followers are mostly broke students aged 18-25, and she can’t expect them to have much disposable income to spend on art.

Wei Choon would disagree, stating that contributing one to five dollars monthly to a page youth enjoy and benefit from is not necessarily unaffordable—again, it comes back to if they find it valuable.

After all, youth are spending on services like Spotify and Netflix, proving they do find value in content. But is all the money being monopolised by giant tech companies and streaming platforms?

I love seeing new technologies and ideas disrupting old ways of doing things. If it’s a better service it’ll thrive.

— Wei Choon.

Such is the promise of capitalism’s free market, and the unforgiving, competitive environment seeking to forge the best products. Sure, consumers are getting a better deal, but is it at the expense of small independent creators?

Even Patreon was a response to these streaming platforms. Its founder, Jack Conte—a musician by trade—found his revenue plummeting since people were streaming and no longer downloading his songs from iTunes. Jack could only earn a mere 10% of what he used to through Spotify.

So how much is genuine innovation, and how much is having enough capital to conduct predatory pricing in order to drive out smaller competitors, earning a loss in the short run but ensuring a monopoly in the long run?

PJ Thum—New Naratif’s Managing Director—posits that we have fetishised the market as an omnipotent, impartial arbiter of value. While market efficiency has its place, there are services which cannot be provided for profit as they are essential to the physical, mental, and spiritual wellbeing of society: services such as security, healthcare, education, as well as the arts and media (which I’ve lumped into ‘content’).

While arts and media shouldn’t be nationalised like other sectors—since they often critique those in power—there should be financial mechanisms for its continued existence beyond the market.

If you’re doubting the importance of content, think about how much you consume. What would life be without digital entertainment, independent journalism, soul stirring art, or high quality memes?

Do we want our media landscape to only have heavily commercialised, focus-group tested content chock full of product placements?

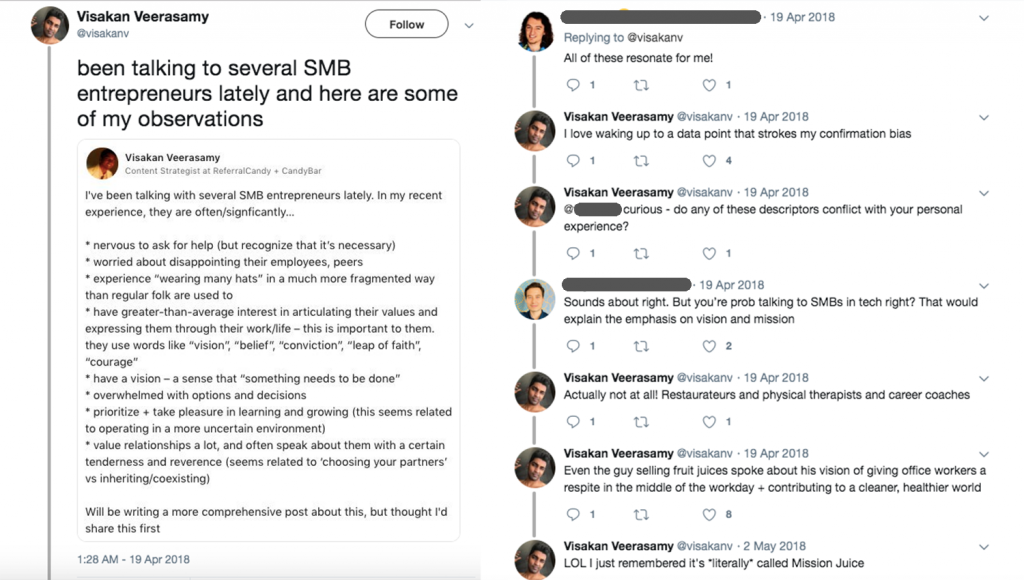

Even though his following of 14,000 on Twitter makes him micro-famous at best, he has 69 patrons who supply him a monthly income of over $1,000 USD. It’s not a livable wage, but it’s substantial enough to alleviate some financial burden.

His secret? Nurturing a passionate community who engages with him, his ideas, and his content. Click on any of Visakan’s Twitter threads and you’ll find him curiously and patiently engaged with friends and strangers alike in constructive conversations.

Community management is the one through-line I see among these hustling content creators. The Woke Salaryman is actively involved with their audience, often responding to comments and asking questions through Instagram stories. They shout-out to their patrons, with the first 100 receiving an exclusive gold enamel pin.

Reakami is grateful she even has her 74 patrons, and she often conducts Twitch streams with them. Because community management focuses on retaining one’s audience rather than growing them, it’s often glossed over. But it’s important to Rea because many cosplay fans follow cosplayers not just for their portrayals of their favourite characters, but for the community built around them.

Communities are at the beating heart of New Naratif, with PJ being adamant that their membership model is unlike Patreon. Members join and support them financially not for the content, but because they identify with NN’s values. The content is simply a means to an end.

Kirsten lays out research done by the Membership Puzzle Project to support this. It’s easier to convince people into putting money towards what you do if there’s a community of like-minded individuals with the same values which your content helps to facilitate and support.

So, value is gained not from the content, but from the community. But I’d like to go a step further and shift our paradigm on content away from the individual value gained.

Remember the theories of value I discussed earlier? As consumers, we’re more inclined towards marginalism—on the constant lookout for the best deal, for utilitarian content that can give us maximum value for minimum cost.

But what if we recognise the inherent value in the labour content creators put into their work, and advocate for their compensation? If you believe a creator makes content that’s worth sharing and worth sustaining—even if you can get it for free, even if the community is nascent—you should support them financially.

We’re no stranger to this concept. We often support loved ones in their endeavours: going to your friend’s or brother’s concert, or visiting your classmate’s new cafe. It’s not about benefiting you, it’s about helping them out.

In gaming communities, audiences can tip their favourite Twitch streamers—even just a few cents. There are calls for crowdfunding on Twitter, where people link their Venmos in times of crisis for others to contribute to.

Rachel tells me of a friend who isn’t a patron, but functions as one, having set up a recurring payment each month to Rachel. It’s all about the relationships, and helping people even if you don’t gain anything out of it.

After all, the line between creator and audience is thinner than ever. As Kirsten tells me, audiences can often be sources of information or expertise, and creators consume content as well which feeds back into their work. Creators aren’t simply authorities making pronouncements from up on high, but are part of and represent communities.

And communities look out for each other.

That’s not how things work now. A passionate few contribute a sizeable amount—many patrons of Singaporean creators can give upwards of $20 a month. But the hope is that as a society, we are able to value the content we consume, and put more towards it.

In essence, if audiences want more well-crafted, thoughtful, NON-SPONSORED content, they have to throw their favourite creators a bone. If we don’t want corporations to pay them—or at least alleviate their reliance on sponsored content—then we have to pick up the slack.

And creators, you don’t need a large audience. You just need one that cares.

Being paiseh like Rachel—who struggles to promote her Patreon—is normal, given the shame and stigma that comes with discussing money in our society. But to get that rice bowl, you have to suck it up and hustle. If you’ve done your due diligence, you’ll find Singaporeans willing to forgo their morning coffee for you.

The economics of our broken content creation model can be fixed, but it will require us to rethink what’s valuable to us.

If your answer is the kind, intelligent exchange of ideas and emotions between people, you best be willing to sacrifice for that.

You can support any of the Singaporean creators featured in this piece: Rachel Pang, The Woke Salaryman, Reakami, New Naratif, Peggie Neo, Visakan Veerasamy, Mynah Mag, and Night Owl Cinematics.

Or if there are any content creators you’d like to shout out to, tell us about them at community@ricemedia.co.