For three days this week, it took me seven hours to get out of bed. My body clock would wake me up at around 5 AM, but by the time I threw off the covers at noon—driven only by hunger and nothing else—I had effectively wasted half the day doing absolutely nothing.

That is, nothing useful, productive, or obligingly done for something else.

In those seven unproductive hours, what I did was loll in bed.

I adjusted my pillows thrice to get a more comfortable view of the Homeland episode playing on my laptop. I read 10 chapters of Educated by Tara Westover on my Kindle, so thoroughly enjoying her knack for storytelling that I lost track of time.

I learnt that the same New York Times writer who’d written about a glitter factory and Kim Kardashian’s soft boobs had recently taken a trip across America on the Amtrak. I watched the entire stream of IG Stories on my feed; one friend shared photos of her F45 class, while another shared photos of his children from the weekend.

I put on my Discover Weekly playlist on Spotify, and discovered two new songs I liked, which I added to my main playlist.

I saved three photos on Instagram as inspiration for my future home. I even took a two-hour nap to make up for waking up at 5 AM, punctuated only by intermittent, half-conscious social media scrolling.

And that was just half of Day One.

This is the part where I wish I could say this essay will extol the endless glorious benefits of doing nothing, furnishing you with tips on how to live your best life.

Yet here’s the uncomfortable truth I confronted after a day: the only reason I hadn’t taken this much-needed vacation before was that doing nothing has always been difficult for me.

Doing something is integral to who I am. From as early as I remember, doing something or planning to do something has been my base temperament; my default setting; my screensaver mode.

When I go on leave, I always plan to accomplish something, at least for a personal project if not for work. In my downtime, I often find myself subconsciously thinking about what I’m going to do after I’ve gotten enough rest.

These tasks may not be related to work, but they are almost always ‘useful’, ‘meaningful’, or serve a bigger purpose beyond being done for its inherent enjoyment. For instance, running to keep fit, reading to improve my writing, or taking a nap to conserve more energy to do more things.

So on my recent trip to do nothing, whenever the impulse to get work done or check my emails surfaced, I forced myself to detach by using Facebook or Instagram to distract myself. I convinced myself that work would always be there when I returned from vacation, and taking three days off wouldn’t make a difference in a 40-year career.

Once, I instinctively reached for my phone to check my Slack notifications at 9:30 AM (the time that work starts), before remembering I was on vacation. I hastily pulled up IG Stories, allowing its ‘frivolity’ to negate the niggling sense of shame I felt from being reminded how naturally I slip into work mode.

If you can relate to this inability to completely disconnect, consider this: it’s not totally your fault.

Doing nothing is the antithesis to hustle culture, which seems particularly rampant among millennials. This “performative workaholism”, according to the New York Times, involves demonstrating how much we love to work by being busy all the time. Our work is deemed more valuable if we’re being productive, though we often forget that productivity doesn’t equate to effectiveness.

This obsession with productivity has become so culturally ingrained that we advocate for doing nothing, just to be more productive. While many articles claim we need to empty our minds to recharge, such as by lying on the grass or going for a walk, this is so we’d regain the headspace to do the work that made it necessary to do nothing in the first place.

In fact, google “doing nothing” and the first link that comes up is an article titled, “How Doing Nothing Helps You Get More Done”.

To do nothing in order to eventually do something is—and I cannot stress this enough—the wrong reason to do nothing.

It took me years to understand this: you should do nothing just because you deserve to do nothing.

But it’s not just about doing nothing; it’s about intentionally carving out time and space to do nothing. While it’s tempting just to dedicate weekends to ‘switching off’, making plans to slack off instructs your mind that doing nothing is important enough to require making an effort for, and it’s not a byproduct or bonus of having ‘spare’ time.

To successfully do nothing requires consciously scheduling downtime, including pencilling it into one’s calendar or specifically dedicating a few days of annual leave to non-purposeful lazing around. By marking it down like any regular appointment, you legitimise the need to do nothing. It is no longer a seemingly frivolous want, but essential to your well-being.

After getting over the initial shock of suddenly having more unstructured time than I was used to, I had zero desire to leave my bed or make ‘full use’ of my time on leave. Even though I was in Bali, and the beach and shops were a mere five-minute walk from my apartment, I had applied for leave specifically to do nothing—a concept I realised was foreign to most people when I told them about my intentional lack of holiday plans.

When my friends found out I was headed to Bali alone, a couple asked me to check out some notable cafes and spas (which I did not, seeing as that meant I’d have to plan my day around visiting them). Others politely asked what I had planned.

To the latter, I replied, “…Nothing?”

Then, noticing the hilarious mix of curiosity, fascination, and confusion on most faces, I reluctantly elaborated, “Just catch up on reading, I guess. Tan. Sleep. Laze around.”

One friend even asked if I was truly planning to do nothing, as though there were a compelling reason to lie about being bone idle. He may be shocked to discover then that I ventured no further than a five-minute walking radius from my apartment throughout my trip, even though it was my first time in this part of the island.

And because I decided against purchasing data for this trip, I was virtually ‘off the grid’ when I wasn’t connected to wifi in my apartment.

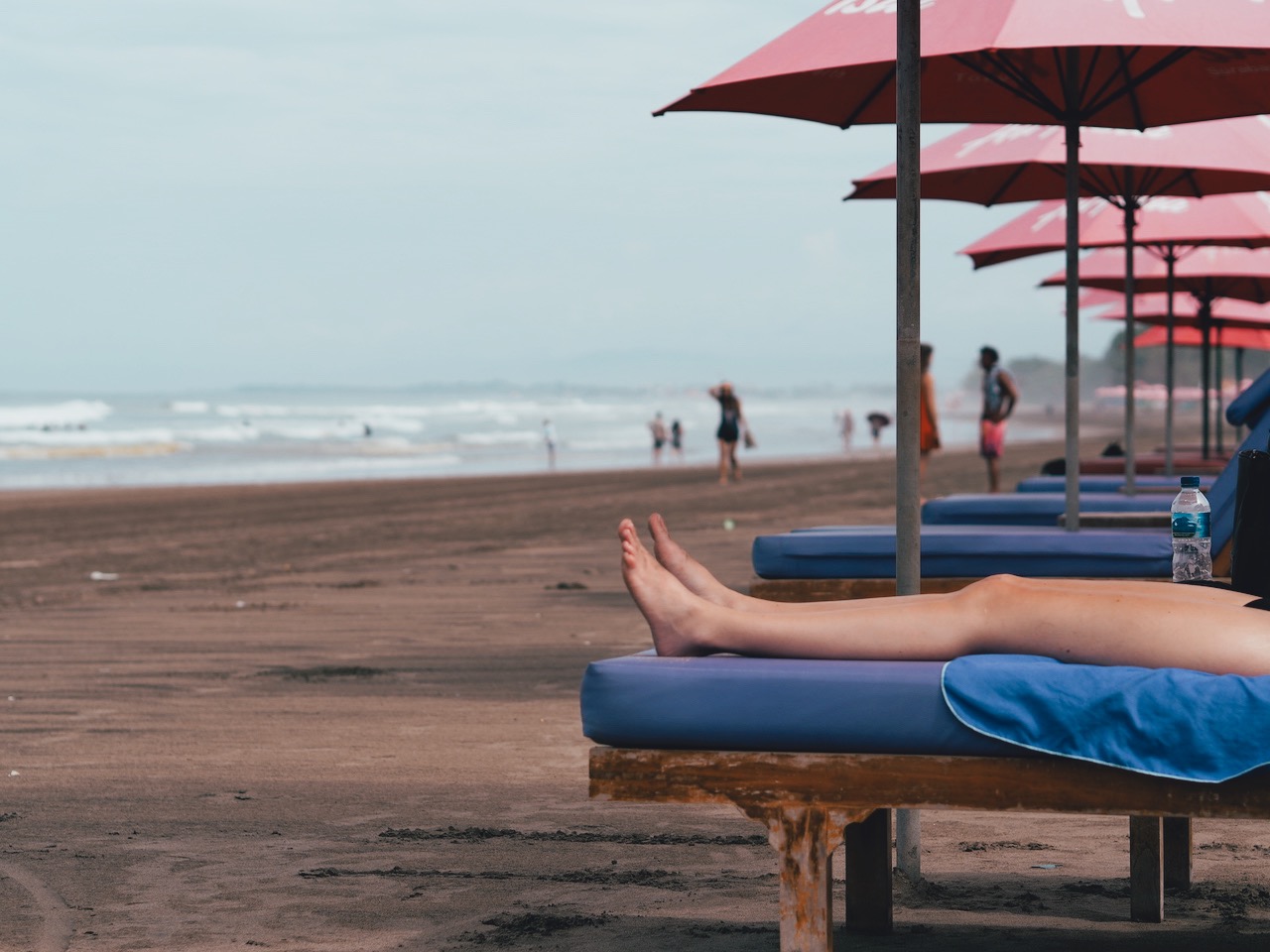

Every day, from the hours after lunch until the sun set, I lay sprawled on a deck chair on the beach, reading, tanning, and drifting in and out of sleep. To give my eyes a break, I watched the ocean rush toward then recede from the shoreline in a steady rhythm, and observed surfers equally hypnotised by the pull of the waves, allowing myself to be lulled into a dreamy languor.

In the evening, having caught the last rays of light dot the horizon, I would then plod back to my apartment, spending the five hours before bed doing exactly what I’d done in the seven hours before getting out of bed that morning.

I fidgeted restlessly to reach the cool spots under the sheets, got lost down a rabbit hole of Facebook comments, browsed the paralysing amount of shows on Netflix only to decide there were too many to make a decision, and replied to texts from friends. I did nothing at all after having spent the day doing nothing at all.

After I’d tasted the delicious and unbridled freedom of doing nothing, I wanted to do everything to prolong the ecstasy. I needed to detach myself indefinitely from reality, and return only when my battery was at 100%. Yet as I soaked up the liberation like a convict who’d just been released, I lamented the limits of my annual leave.

As it is with anything good, the luxury of purposeful laziness tastes so sweet precisely because the high doesn’t—and can’t—last. The first day felt like a month, but each day after felt like barely an hour.

Even so, doing something (or nothing) for the mere joy of doing it, no matter how long the high lasts, is a worthwhile pursuit in itself. It’s not like I didn’t know that my three days in paradise would end, but knowing that and still using all the time to do nothing reminded me: permanence isn’t a prerequisite for happiness.

In fact, knowing that sheer bliss doesn’t last is more reason to make a habit out of doing nothing. If you can’t afford to take a stretch of leave to do nothing, take an extra day off every month. In this way, it becomes so routine that you’d feel like something was missing if you didn’t do it. Turning the art of doing nothing into a regularity also means self-imposed lazy time will actually help you feel relaxed, as it’s supposed to, and not like a thread pulled too tautly that you finally snap.

Thankfully, doing nothing doesn’t mean you have to go overseas at all, even though it does help to be physically removed from a place that reminds you of work. In fact, one of my goals for this year includes applying for leave again to hole up at home, walk aimlessly around my neighbourhood, and take long afternoon naps without setting an alarm.

Before these three days of not doing anything, doing nothing used to make me feel anxious or guilty, as though I was stealing the luxury of freedom that I didn’t earn. While it’s worth noting that being able to do nothing implies a certain degree of privilege, since not everyone can afford to take time off life, these feelings of anxiety and guilt are often misplaced.

There is no romanticism in doing things. Sometimes, it’s just tiring.

In the end, time can be the greatest privilege. So if you have even a day’s leave, then my god, embrace your privilege and go waste it away in bed or something.

As far as vacations go, it was the most pointless, unproductive, and wasteful solo trip I’d done. And entirely necessary.