This piece contains content which is NSFW. Reader discretion is advised.

James and I are having lunch at a cafe near his office. We look like your average young professionals out for a business meeting, which is technically true. Nothing about our meal is out of the ordinary except for our conversation, which, I remember too late, is decidedly not PG-rated.

I’m here to interview James about his experiences as a kinkster—in this instance, as someone who enjoys and participates in BDSM (bondage, domination, sadism, and masochism). He first got into kink when he met his wife, Ellen, on OKCupid; they had both answered ‘yes’ to ‘Are you sexually adventurous?’, though she was the one to introduce him to kink (he was into swinging).

Lest you’re worried for those precious children’s ears, fear not. While most our hour-long conversation was certainly adult in nature, almost none of it was actually explicit.

In fact, I was less interested in the details of his proclivities than in what I, as someone with zero interest in having my nipples clamped, could learn about sex from him.

What if BDSM, despite its association with pain and squick and ~deviant sexual interests~, could actually provide a healthy model for conducting intimate relationships?

Beyond pop-culture portrayals like these—which range from lightly to hopelessly inaccurate—few of us know anything much about BDSM.

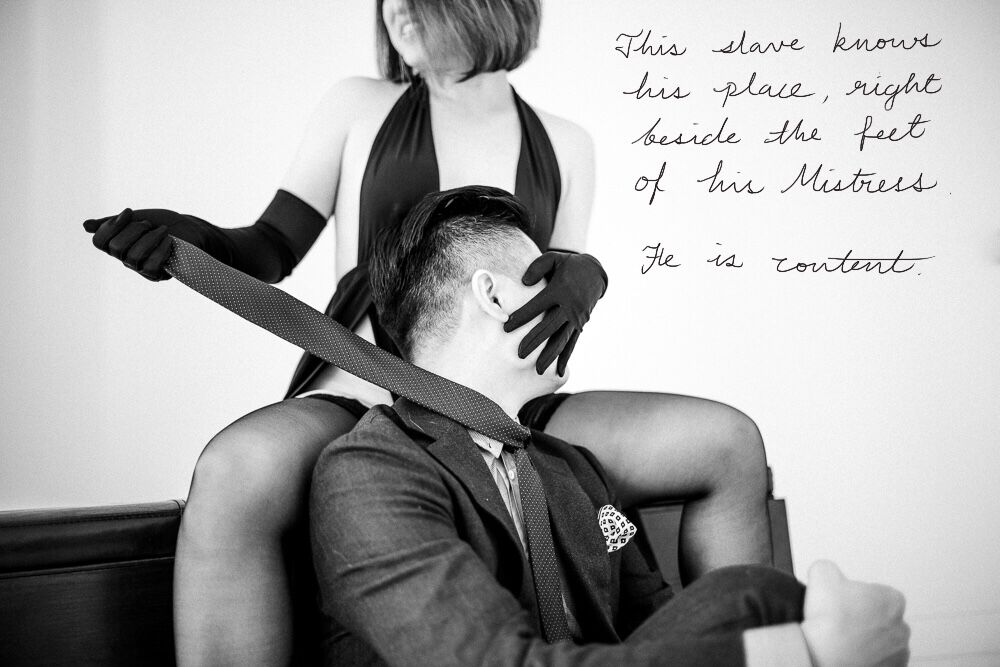

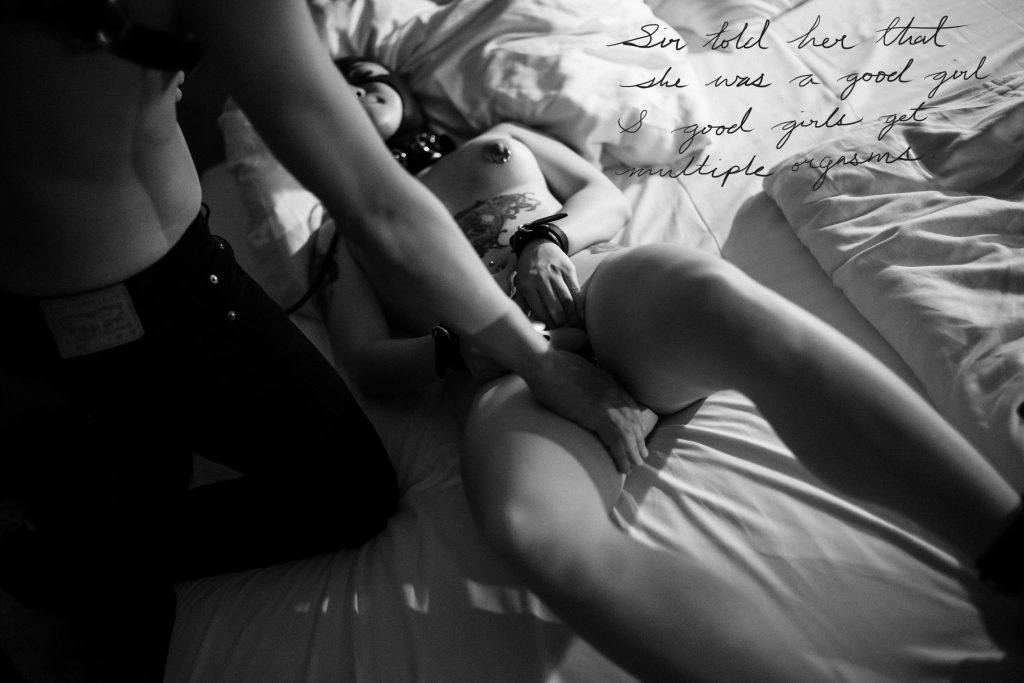

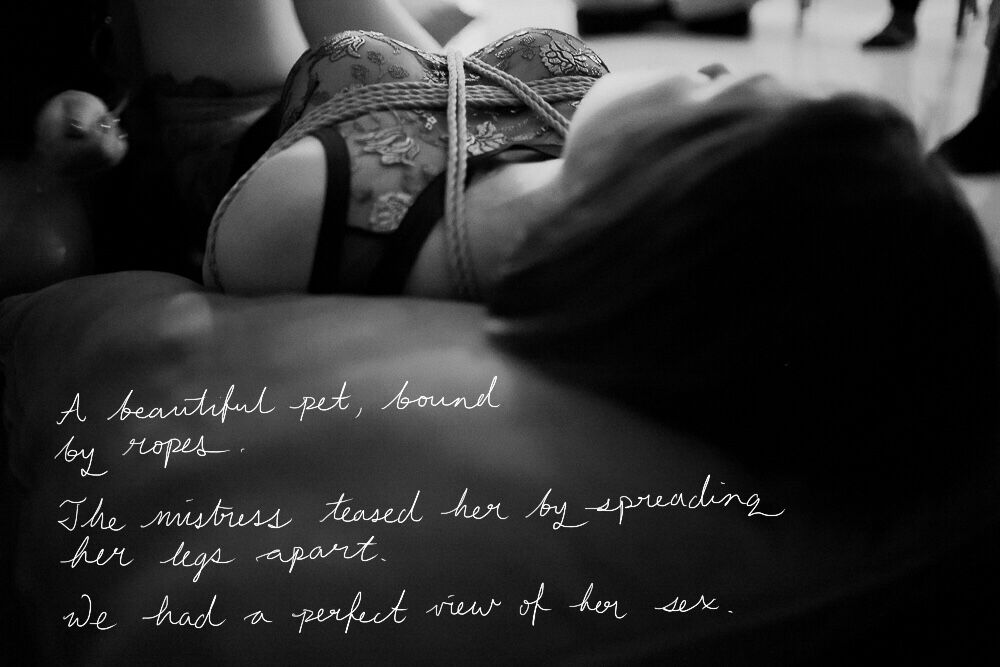

My own (completely theoretical) introduction to BDSM comes from Amber and Lola, two longtime kinksters, whom I meet about a week prior to lunch with James. The former is a full-time professional dominatrix and leading figure in the local kink community, while the latter is an artist who also does erotic photography.

Amber explains that the parent acronym actually represents three sub-categories: bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, and sadism and masochism. Many kinksters enjoy all three and will use a combination of some or all of them in sessions (known as ‘play’), but they can also be kept as separate as participants wish.

In none of them, she stresses, is pain actually necessary. “One of the biggest misconceptions about BDSM is that it’s about violence or that it has to be painful, but this isn’t true,” she tells me. “It can be moderated. Sometimes it’s as mild as being tied up and having a feather run down your body.”

Nor, for that matter, is sexual contact a given. Kink is inseparable from eroticism, but the sex itself is often secondary to the intense physical or psychological effects of play.

“For a lot of people, it’s really about playing with endorphins and adrenaline and knowing just the right amount of sensation you need to obtain that effect,” she adds. “It’s quite similar to people who enjoy going on roller coasters or playing extreme sports.”

Across all BDSM encounters, however, a few things are fundamental: pre-and-post-session discussion, consent, trust, and self-awareness.

Amber explains that it’s standard practice for kinksters to discuss their likes, dislikes, limits, and desired outcomes ahead of a session. While not exactly Christian Grey’s 50-page contract, this is no cursory chat. Most discussions are tremendously detailed, right down to the body part, level of sensation, and type of instrument used, to ensure parties are on the same page.

“For example, someone might specify, “I enjoy ‘thudding’ pain but not ‘stinging’ pain, so a paddle may be used but not a whip,” she tells me.

“A lot of local clients actually tell me not to use canes,” she adds with a laugh. “Too much childhood trauma there.”

Instruments aside, the level of self-awareness this requires is astounding. Few of us—even, or especially, people in vanilla (non-kink) relationships—are used to articulating our desires, let alone in this much detail. Many aren’t sure of exactly how far our tastes extend, or where our limits might lie.

As part of pre-play discussion and negotiation, many kinksters draw up a ‘blacklist’, or list of things that are off the table. The thing is, as Amber points out, most people aren’t aware of their limits till they’ve been crossed. The danger comes when somebody hasn’t realised that something is a red line for them, and fails to include it when drafting their blacklist.

To avoid such situations, she prefers using a whitelist, a list of pre-agreed activities which parties are certain they’re okay with, or at the very least open to exploring. Besides safewords, she also uses a variety of verbal and non-verbal cues to check in with partners, such as a ‘traffic light’ system which partners can use to indicate their level of comfort.

And, she stresses, participants are free to call an end to things at any time.

“As a domme, I have full responsibility for reading the mood of the room and my partner’s status,” she says. “But just because the power dynamics are heightened doesn’t mean control rests only with me. Both of us have to fully consent to something for it to go ahead.”

For this reason, BDSM, despite its association with pain, is actually one of the safest environments in which one can have sex.

Part of this has to do with practicalities—How should I ask? How often do I have to check in?— but, fundamentally, it boils down to our discomfort with talking about sex. To do so opens up a raft of insecurities. What if stopping to ask kills the mood? What if my partner doesn’t find it sexy?

Most vanilla couples will never get into bed with a whitelist ready. Indeed, part of the charm of meeting a new partner is figuring out what they enjoy in bed, a process which inevitably involves trying and failing; sometimes getting it quite wrong before we get it so deliciously right.

How do we balance the joy of discovery with respecting boundaries? How do we ensure sex is fully, enthusiastically consensual without policing it?

When I put this to Amber, Lola, and James, they all suggest that talking about sex, contrary to our fears, need not be unsexy. In fact, it can be quite the opposite.

James’ suggestion is to phrase intent as a statement, rather than a question. “For example, you could say, ‘I’m going to do this to you’, but leave it open for the other person to voice their opinion. It’s not phrased as a question so you still retain that element of dominance, but you remain open to feedback from your partner.”

Trust is key, insist all three. Agree to start out slow, and to stop at any time. Most people respond well to positive affirmation and less well to criticism, so feedback should always be given constructively. If you’re shy about talking face to face, text about it afterwards to start. Just don’t run away from discussing it.

“It could be as simple as saying, ‘I haven’t had anal sex before, but I think I might like to try it with you,” says Lola. “You might be shy at the beginning, but the more you do of it, the easier it gets. And when your partner gives you affirmation, it gives you the confidence to keep vocalising your thoughts.”

James tells me he had never talked about sex so frankly before meeting Ellen, but found it surprisingly easy to get into. Today, when he introduces new partners to BDSM (their marriage is an open one), even those who aren’t into the kink aspect find the open communication refreshing—and are surprised by what a pleasant experience it makes for.

“When you understand what people’s expectations are and you’re on the same page, it’s so much easier to do things,” he adds.

“Talking about sex wasn’t really something I did before I met Ellen, but after we got together, I found that consent could be sexy. That respecting the other person enough to get their consent can be a huge turn-on.”

Throughout my conversations with Amber, Lola, and James, the topic of sex education—or rather, the appalling state of it—keeps cropping up.

“Sex is such a huge part of life, but the way we talk about it here is very biological and functional,” James points out. The exasperation in his voice is evident. “We don’t talk about the cultural or social or emotional aspects of it, but these are all so important. Way more important than, like, maths.”

His words strike a chord. I don’t remember a single useful thing from the sex ed classes I attended in school (although, on reflection, they didn’t seem keen on teaching us anything about sex beyond ‘DON’T HAVE IT’).

Of course, this doesn’t stop most people from eventually fumbling their way into sex. Maybe you, like me, cobbled your own sex ed together via a mishmash of Anaïs Nin’s erotica, tumblr (back when they still allowed porn), and old-fashioned trial-and-error; even if it was awkward at times, nothing too terrible happened.

But inadequate sex ed also means that not everyone is this lucky. There are people for whom it does go terribly wrong.

It means that plenty of young people figure out their thoughts about sex as they’re having it for the first time, and a good proportion of them aren’t sure if this is really what they want but don’t feel able to say no. For others, it means learning about sex through porn, and coming away thinking that jackhammering is pleasurable and it’s normal for women to moan at the top of their lungs, even when deep-throating. It means that many of us spend years lying back through mutually unsatisfactory encounters, wondering why we don’t feel amazing, when nobody told us it was up to us to make it so.

Most of us, yours truly included, sometimes can’t even bring ourselves to say the words ‘have sex’. More often than not, we lean on limp euphemisms like ‘do stuff’.

All of this isn’t just bollocks, it’s sad, and all the more because it’s so unnecessary.

BDSM is often badly served by its portrayals in pop culture, but vanilla sex rarely fares better. How we approach sex, as a whole, is inseparable from a whole host of other issues, from gender and power to romance and religion, and nearly every aspect of the culture we’re immersed in—from the films we watch to the music we listen to and yes, the way we’re taught about it in school—entrenches the exact opposite of what is needed to have good sex.

“We come from a culture where we see someone taking charge as sexy, and unfortunately this means doing things without getting consent, or because we think it’s alpha, that kinda shit,” James points out.

“And regrettably, before I met Ellen, I probably did some of that myself. But it actually takes a lot of courage to ask. It shows you’re not afraid of rejection.”

Towards the end of our interview, he brings up a quote, commonly attributed to Oscar Wilde: “Everything in life is about sex except sex. Sex is about power.”

It’s nice and pithy, but I’d go one further and add: going by our discussion, it’s also about trust. And empathy. And self-awareness. And respect.

None of these have anything specifically to do with kink, or even sex. There’s nothing extreme about them at all. In fact, they sound suspiciously like what it means to be a decent human being.

But the truth is that earth-shattering, toe-curling sex rarely comes naturally.

“For good sex to happen, it’s all about communication and practice, but unfortunately a lot of people don’t think like that,” inists Lola. “A lot of women, in particular, expect men to be mind-readers. They think, I’m just going to lie here and have the most amazing time of my life. But it just doesn’t work that way!”

While speaking with Amber, Lola, and James, and even while writing this piece, I struggled with how the pre-meditated nature of BDSM—the extensive negotiations and postmortems, blacklists and whitelists, even the signals and safewords—could be applied in a non-kink context. Kink requires participants to…well, iron out their kinks before getting into bed (or gags or blindfolds or gas masks). Surely this is too much to expect most vanilla couples to pick up.

Which, I see now, is completely backwards. Good sex is about effort, period. There is no shame in saying that it needs to be practiced, or taught, or learned. The kink community just realised this first, and they’ve probably been enjoying fulfilling sex lives for much longer because of it.

I’m not saying we all need to draw up lists, or interrogate prospective partners about their tastes in bed, but we could make a start by taking ownership of our wants—and talking about them. By accepting that effort is not a concession of weakness, but a triumph of caring. And by learning to recognise ‘May I kiss you?’ as the most breathtakingly sexy question there is.

In other words, to have better sex, have more of it. And talk about it first.

What did you think of this piece? Talk dirty to us at community@ricemedia.co.