Last August, Microsoft Japan implemented a 4-day work week for all its employees. The company closed its office on all Fridays in the month without reducing its employees’ pay or increasing their working hours.

The results were startling: Microsoft Japan reported a 40% increase in productivity, a reduction of all meetings to 30 minutes, and an overall employee satisfaction rate of 94%. Companies across the world that trialled a 4-day-work week experienced similar levels of success in lowering stress and boosting productivity among their employees.

As a loyal employee of RICE, I, too, wanted to boost my company’s productivity. So I brushed aside my colleagues’ concerns for me (“Don’t ask me to cover his stories ah”) and volunteered as a guinea pig in the quest for corporate productivity gains.

This August, RICE implemented a 4-day work week for one of its employees. The company kept its (virtual) office open while I took a day off each week, without a reduction in workload or an increase in my official working hours from Monday to Thursday.

The results were startling: I, the early proponent of working from home, hater of presenteeism, and enemy of hour-long Zoom meetings, hated it.

What happened?

3 August 2020, Monday

The first day of my 4-day work week experiment begins well enough. After RICE’s Monday editorial meeting concludes at 11 AM, I plunge into my tasks right away.

This fact is significant.

Our meetings are feisty affairs in which my colleagues work themselves up arguing over current affairs and politics: parliamentary proceedings, employment numbers, the climate crisis, immigration …

I get headaches when there are too many people talking. The issues that I care about include: dogs, DOTA, and deadlifts.

In other words, RICE’s editorial meetings are like an energy vampire to me.

Hence, after these meetings conclude, I typically take a 15-minute breather before returning to work. Or take an Ibuprofen for my migraine.

Not today. Aware that I would have one fewer day to complete a week’s worth of work, I immediately start editing drafts, replying to emails, and begging people to let me interview them. Throughout the day, I stop myself from trawling through social media, as I usually do when I hit a roadblock in my work or need to distract myself from the existential terror that visits me now and then.

(Admit it— you do it too. A poll of 1,989 full-time office workers in the United Kingdom found that “the average UK office worker is only productive for 2 hours and 53 minutes out of the working day”. 47% fill their workday by “checking social media”; 45% with “reading news websites”; 19% with … “searching for new jobs”.)

Consciously ignoring all these detours, I accomplish more within 3 hours than what I would have had on an average workday. The only difference is that, today, I kept in mind the glittering image of a Friday free to myself. That is motivation enough for me to focus on my tasks.

It turns out that deadlines do work—but only when they serve the individual, not the company.

6 August 2020, Thursday

TGIT~~~*** 😀

Or not.

Only 4 days into my experiment I am reminded of the cruel reality that, in an industry dependent on external clients and the kindness of strangers, my schedule must always be negotiable.

I have a deadline tomorrow—Friday, my day off—for a branded article. Sadly, my profiles are only available on Thursday. One day before my draft has to be submitted to the client.

What to do? Work lor.

Determined to finish my article in one day so I can keep Friday free, and fuelled by a poisonous mix of resentment and entitlement, I plop onto my chair at 7 PM and do not rise till 2:30 AM. Still, the article is not done.

So:

7 August 2020, Friday

I work till 2 PM to meet the deadline. Then I take the rest of the day off, recharging and living a full and active life by lying in bed till dinnertime.

Current level of employee satisfaction: 20%.

8 August 2020, Saturday

The client responds and requests some changes to the article. I edit and upload it to RICE’s website because the client wants it published today. T-o-d-a-y. TODAY.

Time check: 12 PM.

Day check: Saturday.

Sanity check: failed.

To be fair, none of the mad rush was imposed on me by my direct superiors. But it made me realise that a 4-day work week is feasible to teams who only answer to internal supervisors. A client outside the company is not going to care that you are working on a 4-day week: you are supposed to accommodate them, not the other way around.

Herein lies the first problem with the 4-day work week. Most people think of it as a purely internal affair, but which company can afford to operate as a silo in today’s economy?

An article on The Society for Human Resource Management espouses the 4-day work week especially for “employees in the knowledge-based economy.”

“Professionals such as software developers, architects, engineers and physicians,” the author argues, “rely on deep thinking to carry out their jobs, and experts say it’s difficult to maintain such concentration for eight hours a day.”

But it’s often these people—software developers, architects, engineers—who work most with external parties, and will have the most difficulty protecting their time.

Unless a larger cultural shift occurs in which companies in Singapore do not expect employees, and external vendors, even, to be at their beck and call, flexible working hours, let alone a 4-day work week, will remain a pretty speech brought up in Parliament and left to wither in a dormitory.

13 August 2020, Wednesday

A profile asks if I can conduct an interview this Friday. I tell them I am not free. Guilt strikes me; I feel as if I’m skiving off. Anastasia Steele is my name; work is my Christian Grey.

15 August 2020, Friday

I wake up at 11 AM to a bevy of Slack messages, Asana reminders, and emails. The “Work” folder on my phone is displaying a big, angry, red pimple of 1000 notifications.

Still reeling from the guilt I felt on Wednesday for postponing an interview, I go through my notifications one at a time.

They are all inconsequential; nothing that demanded my immediate attention.

Unlike the frenzy of work that I could not escape on my “off day” last week, I voluntarily chose to check in with work even though I had no pressing deadlines because—I’m ashamed to admit this—I felt lost having a normal Friday with no work to do.

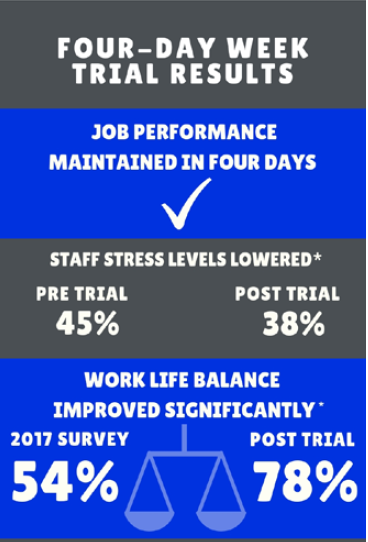

I’m not alone in feeling this way: in a 4-day work week trial conducted by Perpetual Guardian, a New Zealand company, several employees reported that they did not enjoy the experiment.

The discontentment was partly because of “an increased feeling of stress and pressure to complete work tasks within a shorter time frame, especially those facing a deadline”, akin to my experience in the first week.

Others, on the other hand, said they “would rather come to work and see people” because ‘they struggle[ed] to figure out what to do with the day off”.

To institute a 4-day work week, then, requires not just flexibility on a corporate level, but a complete reimagining of what “leisure” and “productivity” mean to the individual and society.

We need to think of rest as productive; of having fun as productive; of having a meal with our loved ones as productive. Or the benefits of having a 4-day work week will be lost to feelings of guilt and inadequacy.

Indeed, the 4-day work week experiment conducted by Microsoft Japan was so wildly successful, I suspect, because the company recognised the need to actively support its employees’ use of this novel free day.

To that end, Microsoft Japan subsidised “self-development related expenses, family travel expenses, social contribution activity expenses” and emphasised that its employees should see the free time for “self-development and learning … for personal life and family care, and for social participation and community contribution”.

Microsoft’s employees, therefore, were not obsessing over ruminations like “are human beings doomed to die lonely”, the way I did on my off day.

Too much freedom, as Sartre wrote, can be terrifying.

I’ll cut to the chase: my 4-day work week experiment failed after only two weeks.

For weeks three and four, my editor instructed me to take Wednesday off, instead of Friday, to see if it made a difference in my mood and productivity.

After that, he promptly scheduled a meeting on Wednesday. I showed up. He forgot that I was supposed to have a day off. I did not say anything. My Wednesday proceeded as per a normal workday.

Next Wednesday, I went to interview a profile, having given up all pretence and effort at sticking to a 4-day work week.

These two weeks, I did my usual Monday to Friday, 9 to 6. And I was happier for it—with a big caveat.

What worked? What didn’t?

I know it’s ironic that I’m making it sound like keeping to a 4-day week was a chore. But it was, because it mandates that a specific day is kept free. This puts pressure to cram tasks into the remaining four days of the week.

But work does not come in a constant flow. For me, some weeks are packed with interviews because everyone’s schedules open up at the same time; other weeks I twiddle my thumbs while waiting for organisations to reply to my fifth email to them.

So what I did these two weeks was take the 8 hours I was supposed to have off, and split them across the week when I had nothing to do. During these lull periods, instead of pretending I was doing (non-existent) work by giving helpful thumbs-up emojis to my colleagues on Slack, I granted myself permission to take long walks with my dog at 5 PM; to go to the gym at 2 PM; to own noobs with my pro Zeus at, uh, 10 AM.

This arrangement worked a lot better because I could return to work whenever something cropped up, without feeling the resentment of having to work on an entitled off day.

In short, the last two weeks of my 4-day work week experiment taught me that flexibility of working hours is a more valuable and efficient way of managing work-life balance and improving mental health than a 4-day work week.

The difference is where agency lies: for a 4-day work week, my time was still dictated by my company; for flexible working hours, I felt in control.

The first sacred cow to be slain is the ridiculous notion that employees have to be physically present at an office, monitored under the watchful eye of a supervisor, or work would not be done.

The time has arrived for the second bovine to be put under the butcher’s block: the idea of fixed hours when everyone has to congregate and work.

A 4-day work week is but a bandage haphazardly plastered over the wound of seeing human labour as uniform and homogenous. For real work-life balance to happen and mental health to improve, control—over their time and their ability to define meaning in their life—should be handed back to the most important personnel of all in a company: the people who do the work.