In the dead of night, Thomas Koh can be found on the second storey of Tiong Bahru Market, washing bags of heart and intestine. As he washes the ingredients, a concoction simmers by the side. A small amount of liver is reserved for a rather skittish cat that resides in the market.

Though this sounds like the start of a clichéd horror story involving witchcraft, the organs in question are pig offal—ingredients for a young hawker’s pig organ soup (猪杂汤) and glutinous rice intestine (糯米肠). And Thomas is the 3rd generation hawker of Koh Brother Pig’s Organ Soup (许兄弟猪什汤), a family-run hawker business that started in 1955 as a push cart.

Earlier, Thomas had told me about an uncited survey that looked at the rarity of his business. It detailed how there are only about 120 pig organ soup hawker stalls left in Singapore, of which only 10 are family-owned. I can’t exactly verify this, but the numbers seem about right. And to my knowledge, Koh Brother is the only hawker left selling glutinous rice intestines, which Thomas concurs.

But why are stalls like Koh Brother so scarce? Why are they the only ones left selling glutinous rice wrapped in intestine?

Offal is often thought of as ‘unwanted’ or ‘discarded’, given that intestines are associated with bowel movements. And much like other organs, like the liver, they boast a texture that doesn’t feel quite the same as meat, making it a bit of an acquired taste.

Likewise, when I spoke to a kway chap stall owner in Ang Mo Kio and another selling chicken feet (both declined to be named) about the perception of these rarer and more ‘divisive’ ingredients, both felt that the items they sell are dishes youngsters “don’t know how to eat”.

The chicken feet seller suggested that “pork chops with pepper” would sell better, probably referring to the frequent crowds a Western stall in the same hawker centre receives.

So it was perhaps a little surprising to find Koh Brother with its fair share of loyal customers on a random weekday afternoon. While not the hour-long queues you find at Michelin-starred hawkers, you wouldn’t say that business isn’t good either. Using this crowd as a reference, you might actually say that Chinese Singaporeans love offal.

Despite offal’s apparently declining popularity, all the stalls I spoke to still command a significant number of regulars. Koh Brother, in particular, still has people coming specifically to eat their glutinous rice intestines.

And so I couldn’t help wondering: why do people really like these divisive ingredients? Is there some kind of a secret to unlocking one’s love for offal?

Perhaps the best way to understand is to try the food for yourself.

Koh Brother’s soup is tangy from the Kiam Chye (salted vegetables) and peppery with a clean taste best described as homely and satisfying. It’s a soup that seems to cleanse your soul, with absolutely no odour.

With offal cooked to be slightly chewy, it might be mistaken for sotong if not for the shape. For a complete experience, eat the soup together with the glutinous rice intestines—to be dunked into the chili.

Mrs Koh proudly mentions that kids as young as 5 years old patronise their stall, often together with their families. Some are even more discerning than their elders in eating offal. Thomas later elaborates on this with a theory—echoing some of the hawkers—that people who ate the pig’s organ soup or offal in general while growing up would like the dish. And while it is harder to find people of the current younger generations who do so, this suggests that perception and taste are often based on memories or past experiences.

A common description of offal-based dishes on the web, even for those in other cultures, seems steeped in nostalgia or descriptions of ‘homeliness’. The words “home cooking” often bring to mind simpler times, and the image of a mother or grandmother patiently cooking a dish for long hours.

In fact, ‘long hours’ describes the business incredibly well.

Nearing midnight, there’s activity at only a few other hawker stalls at Tiong Bahru market. Most are in the midst of packing up, and Thomas is the only hawker still preparing for the next day’s menu, which must be ready to receive customers by 8.30 AM. This requires them to reach the stall at about 7 AM the next day. While the 5-person team operates on a six-day work week, even on their off day, there might be prep work.

This isn’t uncommon for stalls selling offal-related dishes. The kway chap stall in Ang Mo Kio starts its day at about 5 to 6 AM (for prep), and ends its day between 9 to 10 PM. The reason for the long hours is simple: offal requires an ungodly amount of time to wash and prepare.

I was initially surprised to find out that frozen offal is pretty much the standard that’s used these days, given that so much time is still spent cleaning. After all, most food is required to be cleaned prior to packaging and freezing. I was under the impression that working with frozen food would be much easier.

As it turns out, frozen offal is cleaned—but to completely remove the smell would require even more cleaning. Otherwise, it would literally taste like shit.

Once upon a time, when fresh offal was used, it was even more tedious, and a hawker’s day would end a couple of hours past midnight. Now, defrosting replaces the first stage of cleaning.

As a sceptic of the claim that frozen pork is fresher, I had questioned Thomas as well as the unnamed kway chap stall about this. Both said they actually found negligible differences. In fact, frozen might sometimes even be fresher, given the flash freezing process, which preserves meat freshness right after slaughter, killing bacteria in the process. The only way to get any meat that’s fresher is if the farms are located in Singapore.

(Fun fact: the use of frozen meat is a consequence of the Eat Frozen Pork campaign, a government initiative started in 1984 to encourage the use of frozen pork as a healthier, fresher, and cheaper alternative during the phasing out of our domestic pork industry.)

While the unnamed kway chap stall tells me that they might recommend customers different parts based on preferred texture, Koh Brother has a different philosophy. Here, each type of organ is prepared and cooked separately to achieve a similar, soft texture.

Prep for the organs happens twice: in the afternoon, and then again at night. In the case of pig’s heart, sinews are removed before it is cleaned. This happens during the day, and only later at night is it cooked.

Pig intestines, both large and small, come in a frozen, entangled mess. As the intestines are cooked differently, they need to be separated. Separated intestines are washed with salt and rinsed in a manner akin to hand washing laundry. Intestines that are suitable for glutinous rice are set aside for the dish at night.

David, who showed me how they clean the intestines, isn’t actually part of the family. To Thomas, David is a friend close enough to be a brother, even though he only started helping out about half a year ago.

Much of the work is done in the stall, which can’t be larger than 5m by 5m, with the majority of the space filled with simmering pots, a large vat of warm rice, buckets of ingredients, and a small counter for cooking upon a customer’s order. Everything is packed to maximise the usage of space.

A slight misstep, and you might burn yourself or knock into something.

In the claustrophobic space you’ll find that heat is another challenge. Mrs Koh jokes that the stall is a free sauna, and the fires in the small kitchen might have smoothed out Thomas’s legs.

A part of me thinks this isn’t entirely a joke. When I moved close to the simmering pots, my own legs felt a little something. Of course, I wasn’t in that position long enough to find out if this would turn out to be successful, involuntary leg care treatment—there wasn’t enough space even if I wanted to.

The next part of the prep happens after dinner service, at about 8 PM, when there are few customers. Without the interference of pesky customers buying food, I could finally sit down and properly speak to the family, each of whom is separately performing their own tasks.

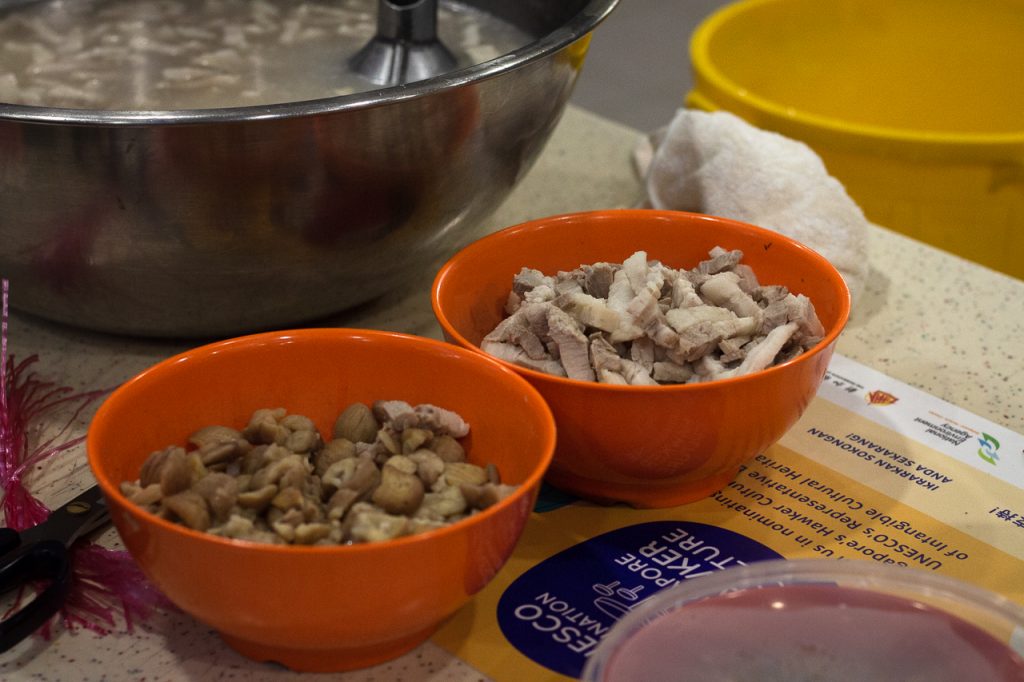

Glutinous rice intestines are mostly prepared by Mrs Koh, who stuffs a mixture of pork meat, glutinous rice, and chestnuts into the intestines by hand. The trick here is to stuff the intestines underwater so water pressure will pack the rice sausage tight.

The day after, these will be boiled and cooked, although not all intestines have suitable membranes for the rice mixture. Unsuitable ones result in ruptured intestines that leak, a surprisingly common occurrence. For this reason, stuffing the rice can only be done by hand; most machines are not sophisticated enough to discern between suitable and unsuitable ingredients.

Although they do have a cutting machine and are trying to find something that can potentially reduce their labour, most ingredients in the stall are still handled by hand. Other than the intestines, for example, Kiam Chye differs in size and taste according to season and other reasons that might affect the supply. Water chestnuts are another such ingredient, and need to be peeled by hand.

“If it weren’t for (the glutinous rice intestines), I’d be going home already,” Mrs Koh tells me in Mandarin.

Glutinous rice intestines is part unique selling point for Koh Brother, and part preservation of the stall’s long history.

I asked Thomas and Mrs Koh if they would follow other pig organ soup stalls to sell only white rice, but they aren’t open to the idea. On this point, Thomas seems slightly more insistent on keeping to tradition. To him, there is a sense of responsibility because of the rarity of their business.

Offal used to be much cheaper in the past, compared to meat, and in certain cultures, they were the food of peasants or slaves. But according to the Koh family, the perception of offal as undesirable wasn’t common in Singapore. Today, offal is no longer cheap.

An educated guess points at globalisation as a factor: even if offal is regarded as inedible in certain cultures, countries like China, Hong Kong and Vietnam, that are huge consumers of edible offal, will continue to drive demand. China, in particular, is expected to import even more pig offal in the coming years (here’s another blog post for perspective) as the largest pork consumer per capita in the world. Basic economics at work here. Demand means price will be kept up without an increase in supply.

To Koh Brother, high ingredient costs translate to lower margins for the business, and this isn’t even taking into account rent and other costs.

Consequently, the opportunity cost of not running the stall is high, leaving little occasion for holidays or breaks. This also means that there is little room for experimentation with the recipe, something Thomas hopes to do. In particular, he wants to recreate the flavour of pig’s blood (now banned in Singapore).

Back then, pig’s blood came with the soup in a tofu-like form, giving a sweet, additional umami to the soup. Even further back, pearl vegetables (珍珠花菜) also went into the soup, although their grassy pungency required them to be paired with pig’s blood.

As for the future of Koh Brother, I asked Thomas if he had ambitions to perhaps open a chain one day. Modestly, he talks about wanting to focus on the current recipe and stall. Even if he wants to open another stall, manpower and quality control would be another issue.

I linger for the rest of the night, observing as hawker centre patrons gradually leave and stalls close. By the time the rest of the Koh family has gone home, leaving Thomas to do the final cooking and simmering for the soup, only a dessert stall, a Cantonese tze char, and a beverage stall remain open.

The offal from noon is once again washed, and then cooked separately before everything is settled into a giant stock pot to simmer until the next day.

Salted preserved vegetables, or Kiam Chye, are washed twice before being added to the soup. Kiam Chye also happens to be the name Thomas has given to the skittish cat I mentioned earlier.

Finally, at the end of all the prep, a cat’s serving of pork liver is cooked, to be delivered to the last customer of the day on the rooftop.

Reflecting on the story behind Koh Brother, I can’t help but feel a tinge of regret. How many stories like theirs are still untold? What will happen to the dishes that don’t have someone like Thomas, who’s around to ensure their longevity?

Furthermore, food that adopts a no-waste philosophy often comes with some kind of discrimination, based solely on the undesirability of the ingredients used. Perhaps some people might never understand the appeal of offal, beef lungs, chicken gizzards, bone marrow, or liver.

But from my point of view, it is comforting to know that an animal which gave its life for our consumption is given the appropriate respect with its full utilisation. It is equally comforting to know that someone bothered to go through the labour to give otherwise unpalatable parts new life in a delicious form.

Obsolescence might be the future for some of these stalls, but the ones remaining are the hidden gems waiting to be discovered in our diverse culinary landscape.

Koh Brother was found through Burpple, which sponsored this article. FYI, Burpple is also a fantastic tool for locating hidden gems like Kway Chap, Nasi Padang With Beef Lungs, chicken offal, and Sup Tulang.