T:>Works is an independent performance company based in Singapore. It seeks to investigate the current urgencies of living in Singapore through different creative expressions in the public sphere. From 13-31 July, T:>Works presents ‘Festival of Women: N.O.W.’ a completely digital experience which makes the vulnerable and private public, to get to the heart of female intimacy.

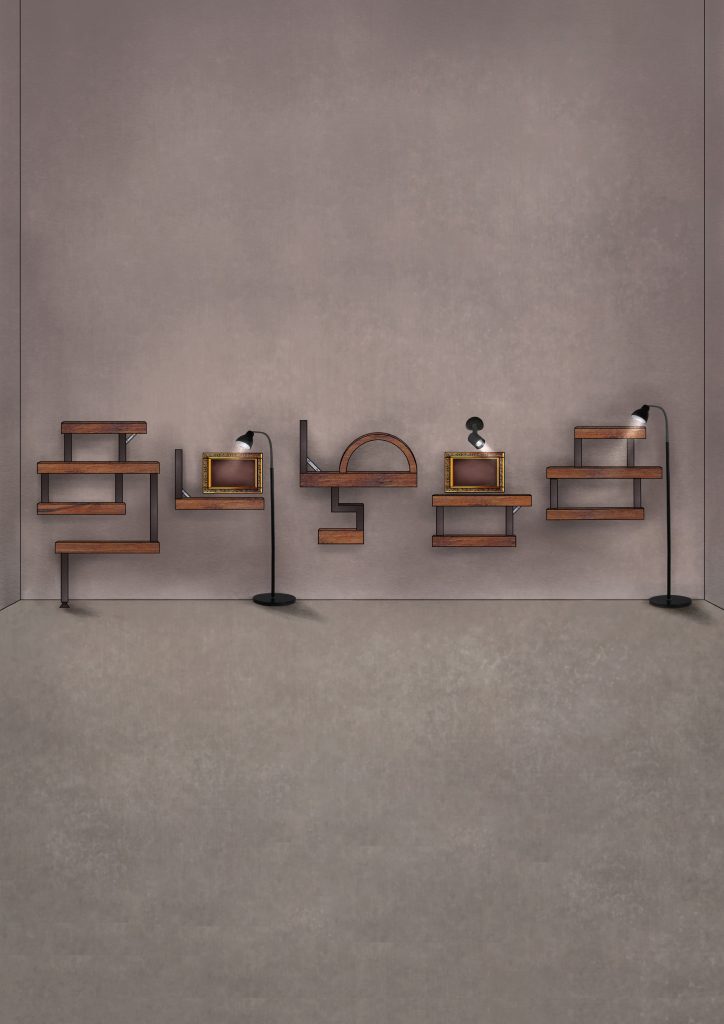

Below is our conversation with Vithya Subramaniam, creator of Thamizhachi: A digital museum of Tamil Women Under Construction and writer-performer of Rasanai: An Invitation to Appreciate. She presents these pieces as a member of Brown Voices, a collective of Singapore Indian playwrights. We wanted to know more about Thamizhachi, the digital gallery that she curated which can be viewed here.

What was the inspiration for Thamizhachi, and how did the collaboration come about?

In part, Thamizhachi: A digital museum of Tamil Women Under Construction is an expansion of my interest in the relationship between humans and objects and in the museum form. When the opportunity came to create a piece through which the Tamil woman could be made visible, centering the work on objects offered a way to demonstrate that her presence is profuse, it’s everywhere, it’s the everyday. The collaboration came when Brown Voices was invited to present a piece with the Festival of Women N.O.W. this year.

During COVID, traditional art experiences have been limited. What were the benefits of presenting Thamizhachi as a digital gallery, did the boundaries of this medium surprise or rejig the creative process?

On top of the practical benefits of being able to continue functioning in these times, the digital format also means we can continue to take visitors and their contributions for a really long time, far longer than we would be able to afford rent on a physical venue. Importantly, in a physical venue, the museum will present as a completed, authoritative collection. The digital format thus lends well to the ‘under construction-ness’ of the museum in both function and form.

Can you describe Thamizhachi’s mission in three words?

‘Thamizhachis are here’— and by that, I mean that this piece is about reminding us all that Tamil woman is and always has been here; it’s then about making her presence visible; it also reminds us of the need to center the subject in the process of making Thamizhachi, the digital museum.

The Singaporean identity is in flux at the moment. COVID and the recent outbursts of xenophobia, and racism have highlighted the dark side of nation-making. Online, we’re seeing a collective push back against organisations such as the People’s Association. Local officials are struggling to respond to criticism with nuance. The Thamizhachi gallery cites identity as ‘perpetually under construction’, how could this understanding of identity as an ongoing construction add to the national conversation on racial harmony?

The Singaporean identity, as all identities are, is in flux… not just at this moment, but always. The sooner we recognise that we are all constantly negotiating and making our place in an evolving idea of ‘Singapore’, the better off we will be. But Thamizhachi as a piece is not a solution to our issues with racial harmony, it never set out to be. If we truly value our racial communities, we must value their works equally. Unless they set out to do so, we mustn’t burden the work by or about minority communities with the mammoth task of nation-building. We must instead actually listen to these pieces for what they are and what they set out to do. In this case, Thamizhachi and the extended exploration, a one-night-only performance Rasanai: An Invitation to Appreciate are works of recognition and appreciation of the Singaporean Tamil woman. They are works of celebration. Sometimes, we just want to celebrate ourselves, that is all and that is enough.

How did your respective fields of expertise inform your approach?

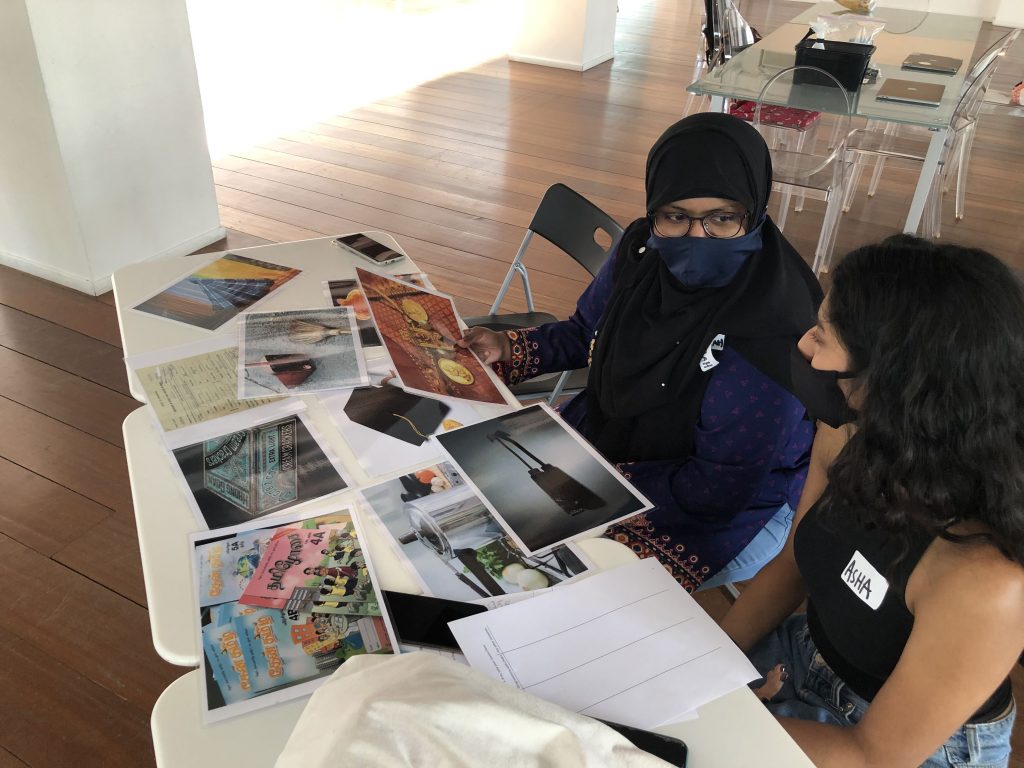

In anthropology, we try to stay conscious of the subject’s hand in the production of our study. So, it was important to me that the subject of the piece, the Singaporean Tamil woman, was herself involved in its making. That’s where the collaboration through workshops came in. Having studied the history of the Indian community in Singapore also meant that I came into this process already knowing that we have a wide pool of possibilities to pull from. Ultimately, my task was to present these possibilities to the participants and get a sense of their priorities in this piece of representation that we were making together.

Was there a personal catalyst (an experience of othering or a conversation with a friend/family member) that inspired the beginning ofThamizhachi?

That’s quite hard to pinpoint. It’s tempting to think of inspiration as linear cause and effect, but it’s always there. I have always been and will always be a ‘Singaporean Tamil woman’. Intentionally or not, the particular perspective afforded by this way of being will never not inform my work. But something might happen at the right moment to remind us of what we’ve known for a while. As we were considering what we might put up for the Festival of Women N.O.W., someone told us that when they think of Indian women in the arts, they don’t picture any of the Tamil women practitioners. Imagine someone telling you to your face that, essentially, they do not see you. That episode reminded us that this is the way many people think across industries and fields. Even when they know individuals personally when it comes to the collective group of ‘Tamil women’, this group is largely overlooked and worse, looked right through. The irony may be that precisely because the Tamil woman, the sari-clad Tamil woman, is the most visible token version of the ‘Indian’ figure, the real breathing, variable, multidimensional Tamil woman becomes rendered invisible.

Objects play an important role in this digital gallery, can you elaborate on the importance of the material world in the construction of personal identity?

We live in a world where we are constantly spoken for by objects—our NRICs, ID and access cards, even tissue packets that speak for our impending return. Material objects enact our ways of being all the time, naturally, they enact our identities and all the ways we construct ourselves. Instinctively, we recognise this when we keep some things and trash others.

Is there one particular object that captured your attention in a surprising way?

Initially, I was wary of reproducing the token image with objects like the sari, thali, and pottu. But through the workshops, I saw how these Tamil women themselves had complex, nuanced, long-lived relationships with these objects, actively, consciously engaging these objects in their own construction of self. So those surprised me, the objects that I initially dismissed as tokens.

What feeling or idea do you hope to leave viewers with as they view this exhibition?

I hope visitors recognise that self-definition is in their own hands, that anyone has the power and resources to change the way they and/or their community is represented.

Check out Vithya Subramaniam, Brown Voices, and the Festival of NOW 2021 presented by T:>Works.

If you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook and Telegram. If you have a lead for a story, feedback or just want to say hi, you can also email us at community@ricemedia.co