How the hell did I get here?

Oh, right.

“Starting from your status quo, you will experience worsening environmental conditions due to climate change. To survive, you will have to journey long distances and overcome obstacles in order to reach a safer place,” I recalled, thinking back to the event description for the Refugee Experiential Walk.

Nevermind how patronising and insensitive such an event could turn out to be. Nevermind that I was someone who’d rather spend the day lounging around the house in PJs than cavorting around the island pretending I was fleeing some war.

The little devil on my shoulder urged me to try it out. It’ll be fun, I thought to myself.

That was my first mistake.

As we were all still in the ‘status quo’ period, my ‘family’ did what all Singaporean families did: eat. Little did we know that was to be the last of our creature comforts for the rest of the day.

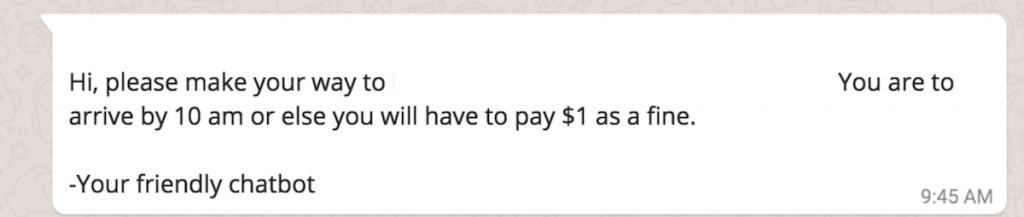

Halfway through the meal, we received this message in the group chat.

Nevertheless, we hightailed it to the address but still found ourselves 7 minutes late.

“$5 please.” Said Abhi when we reached our destination.

“$5? It was $1!” someone protested.

“Each.”

Oh. Oh well.

That’s alright I told myself, it was only $1 and besides I’m sure refugees had it much worse.

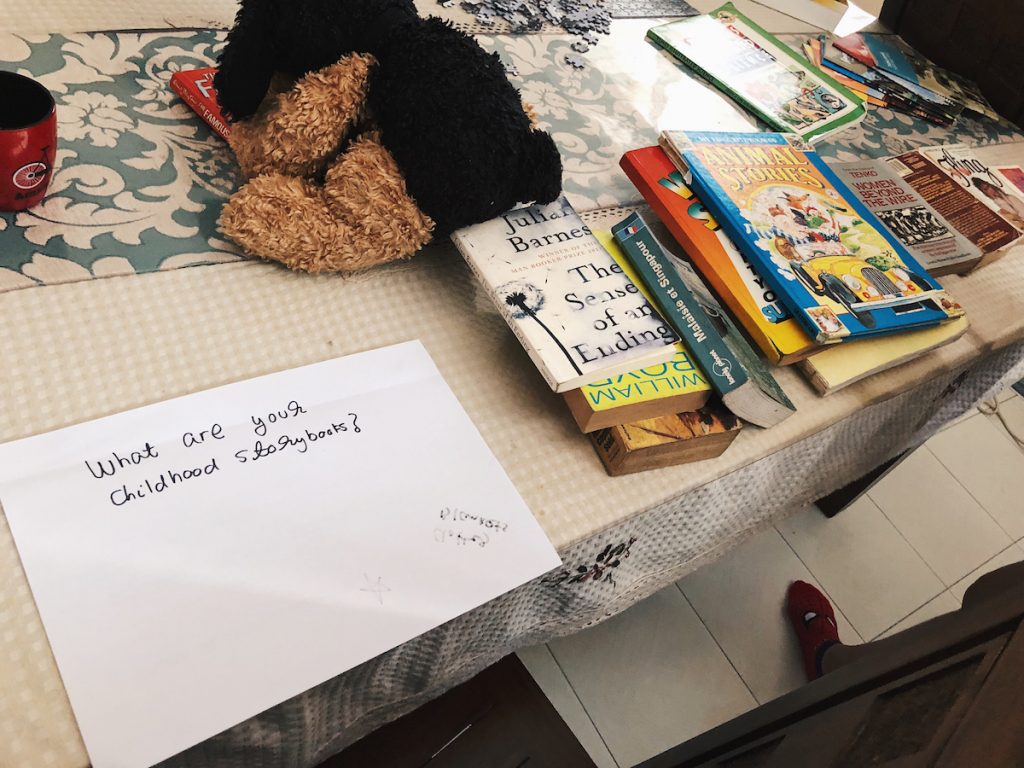

As it turns out, we had in fact come to Abhi’s home. We walked through his house, imagining that it was our own, and we were surrounded by the people we loved and the things we owned.

Only we weren’t. “It was weird,” remarked a participant. “It’s hard to connect with it when you’re in a strangers house, surrounded by more strangers.”

In Abhi’s living room, we were gifted with our very own passports and shown on his TV a snippet of Peter Parker vs. Flash from the 2002 Spiderman movie.

Midway through the clip, just when everyone was enjoying seeing Toby Mcguire kick some ass, the broadcast was interrupted by a emergency report detailing flash floods in the eastern part of Singapore along with a call for evacuation.

The room was silent for a while, the ghost of Spiderman’s unfinished movie hanging over us. And then slowly and begrudgingly, we got up and shuffled out of Abhi’s house, ignoring his previous instructions to evacuate and run down the stairs quickly.

Some people even waited for the lift.

Eyes closed, we proceeded to shout, scream, jostle and step on each others toes.

The activity, meant to mimic the difficulty of trying to locate our loved ones in a chaotic environment, resembled more the experience of shopping at Sephora on a weekend.

When that was done, we were instructed to empty our backpacks on the floor to evaluate what we’d brought—I only felt mildly horrified as I unpacked several sanitary pads from my bag and laid them on the ground for everyone to see.

Before the walk, Abhi had sent us instructions to pack for a week away from home. As I only happened to have read said instructions an hour before the event was to start, I only brought enough for the half-day event.

I wasn’t alone, there were a few who came with just fanny packs and some without a bag. Logically, as the event was advertised as a “walk”, I doubted anyone with a sound mind would want to walk around Singapore dragging a week’s worth of supplies with him/her.

Most of us had brought the standard items: biscuits, money, an umbrella and water (one genius even brought a can of coke), but we all lacked the important stuff: tools, medication, sanitation supplies and an instinct for survival.

We wouldn’t last a week.

As we journeyed there via bus, we were Whatsapped several poems written by actual refugees to read and reflect on.

While a great idea, it was not without its problems. For one, they were PDF files. Large ones that required data to download. Second, we were on a bus and the incessant yakking of an auntie berating her husband for not buying her lunch didn’t make for a very reflective mood.

I’m sure the poems were great though.

At Changi, we were given instructions to meet up with a ‘smuggler’, a role playing friend of Abhi’s who would be taking to us to the very safe land of, you guessed it, Pulau Ubin.

The catch was we couldn’t buy the tickets ourselves but through the ‘smuggler’. And even though a ticket to Ubin cost $3, we were quoted a price of $12 and after 10 more minutes of negotiations, $6.

Others were quoted $8.

Sure I understood that this was part of the whole ‘experience’ of being a refugee and being forced to pay exorbitant sums for safe passage. Perhaps the frustration was even intentional, meant to recreate in us the feelings of helplessness and anger felt by refugees who just wanted to get someplace safe but couldn’t.

Yet standing in the middle of a crowded hawker centre, it was all too easy to disassociate myself from the identity of refugee. $6 wasn’t much, but I still I struggled to justify paying it to someone I didn’t know to be taken somewhere I didn’t want to go.

It’s one thing to do it real-life, in a real refugee crisis, but another thing entirely to role play it.

“You don’t need to do this,” urged the small voice in my head. “You could just drop out, have a good lunch, go home, save yourself $6 in the process and the rest of your afternoon.”

Tempting, for sure. But out of consideration for my ‘family’ who I had come to rather like, and out of respect for the organisers and their efforts, I paid up.

Not everyone did, however. 2 family members decided to drop out at this stage claiming injuries.

We were lucky they said. Of the 20 people who had started the journey, only about half of us had made it this far. Lucky, indeed.

From Ubin, we were told to make out way to the Northernmost part of the island either on foot or by renting a bike.

Did it cross my mind that real refugees probably wouldn’t have bikes? Absolutely. But it was 1 PM by then, the sun was out in full force, we hadn’t eaten since 9 AM, and there were mosquitoes.

So to the bikes we went.

Once at the campsite, we were instructed by ‘more senior refugees’ (aka more friends of Abhi) to build a refugee shelter.

Now if this exercise was meant to convince me that I’m not built to go camping, it was a stunning success. If it was meant to showcase the poor living conditions and difficulties refugees go through when settling down in a new country, it failed spectacularly.

Although we were encouraged to use the raw materials around us like twigs and tree branches, we were also supplied with large plastic sheets, a 12 ft long banquet table cloth, wooden pegs, rope and raffia strings—materials I’m guessing most refugees won’t have on hand.

No prizes for guessing which items we went with.

This was our tent, and it took a grand total of 5 minutes to assemble.

In our enthusiasm to get started, we had also pitched our tent too close to the shore line—a good idea only if we ever wished to transform our tent into an indoor swimming pool during high tide.

Simply put, our shelters were completely useless and more of an embarrassment to the survival efforts of refugees than a homage to their struggles.

It was time to get moving again.

This time round, we were headed to the opposite end of the island, the Southernmost part at Jelutong campsite for our ‘immigration point’ and final destination.

All things considered, I was starting to get a better handle of what it felt like to be constantly on the move, to not have time to get comfortable nor settle down but to be continually displaced.

The only difference was that I could see the light at the end of the tunnel (4 PM, please come now). I knew that it would soon be over and I could put this experience entirely behind me. Refugees couldn’t, and that made a world of difference.

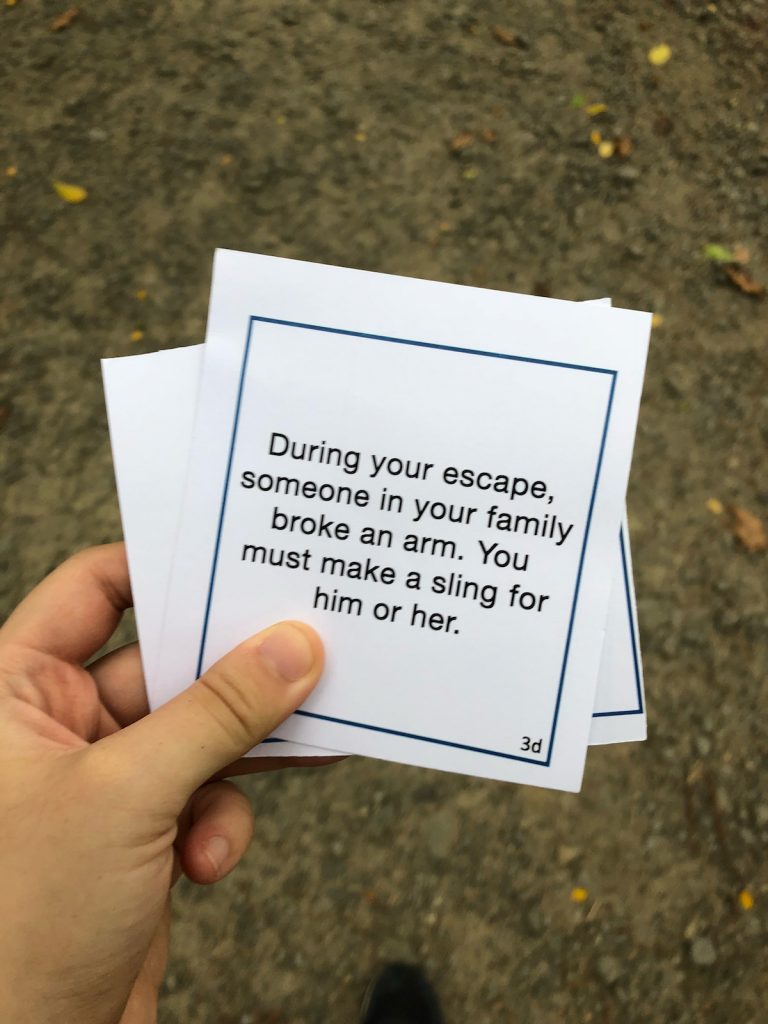

For the journey there, Abhi decided to make it extra hard on us by putting one of our family members’ arm in a sling and banning us from using our bikes (that we’d paid for).

It was a good rule, for all of the ten minutes that we followed it.

Once the sky darkened and the first bolt of lightning lit up the sky above us, we hopped on our bikes and rode the rest of the way.

What fools would we have to be to walk in the rain when we could ride?

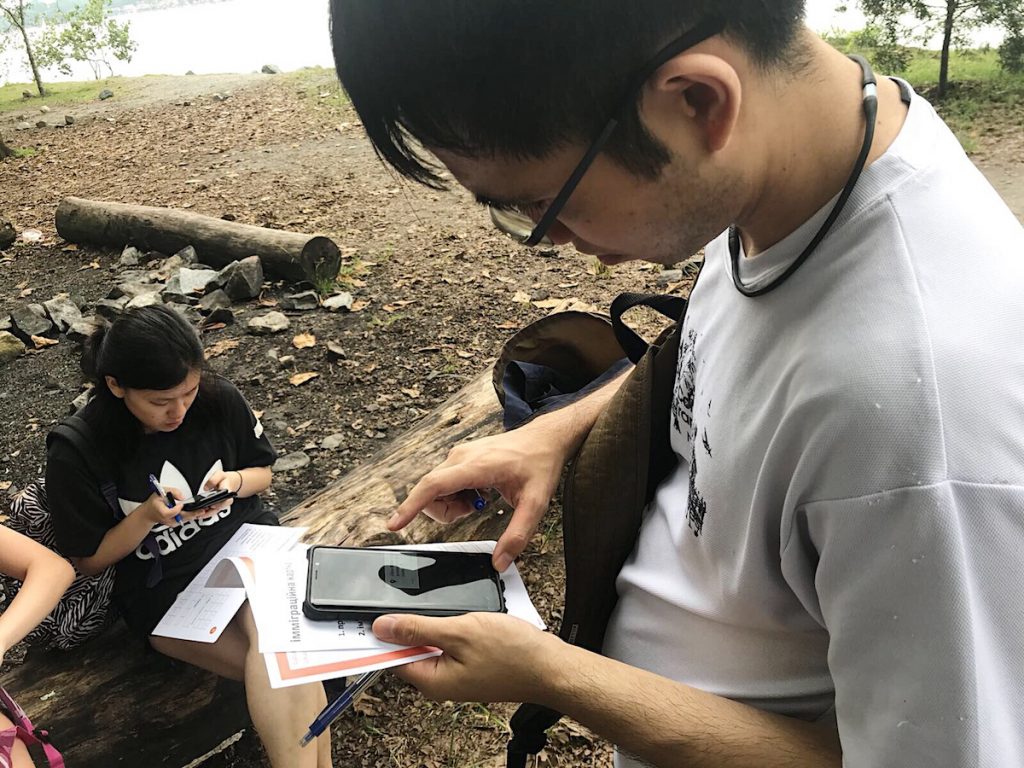

As expected, none of us happened to understand Russian. What we did understand though, was how to use Google, and how to copy off each other. Using a combination of Google Translate, a Russian keyboard, and “Eh what is number 4 ah?” we filled in our names, fake passport numbers, nationality, address and date of birth under the requisite boxes.

“You know, if we cheat and just anyhow write they also won’t know,” said one of my family members.

I nodded in agreement and we abandoned Google in favour of scribbling several random shapes together. It looked Russian, only it wasn’t.

But it didn’t matter, it was past 4 PM and everyone, including our faux immigration officers were itching to go home.

With barely a glance at our gibberish immigration forms, we passed, our fake passports were stamped and we were finally free.

It was a novel idea, especially in Singapore where refugees are unheard of, rejected before they can even contemplate making their way to our sand-imported shores.

Did it make me more sympathetic to the plight of refugees? Yes. Did it illuminate just how spoiled, and unprepared I was to face a world without Singapore? Absolutely.

But would I do anything with this knowledge? Probably not.

Truth be told, Abhi’s walk was more a test of my imagination and willingness to cooperate than my survival and endurance skills.

If I wanted to better appreciate the plight of refugees, educating myself via listening and reading up would prove a much better strategy than pretending to be one.

Much like stepping into the shoes for a day of someone who’s deaf, mute and physically disabled, you can just as easily step out and when you finally come to light at the end of the tunnel—and you will—you can shake off your false identity and go back to business as usual.

As one of the participants told me, “It seemed like a good idea at first.”