We’ve been labelled the “lost generation”.

A global pandemic. Record unemployment. Life plans shelved. Dreams disrupted. This is the way 2020 ends; not with a bang, but with a whimper.

With no end to the Covid-19 crisis in sight, one thing’s clear: it has become critical for us youths to step up and take charge of our own narratives—to have a voice, and to use this voice to shape our present and future.

Take the sheer power of the vote, as we’ve witnessed in a year dominated by watershed elections abroad and at home. In the recent United States presidential election, surging youth voter turnout propelled Joe Biden to a decisive victory. In Singapore’s July general election, young voters who desired to see diverse voices and more checks and balances in parliament lifted the opposition to its best-ever showing.

Voting is a right; a deliberate exercise in political participation. Yet surely it isn’t the only way for us to have our voices heard. How our generation chooses to make a political statement can vary in form, measure and tangibility. Some prefer the covert, starting by influencing social circles within reach. Others head to the streets in mass movements. Others take to the web.

But democracy is not a universal privilege—it’s a loaded concept that exists in spades and shades, all too often accompanied by caveats. For the disenfranchised trapped in environments besieged by violence, state censorship, or an erosion of basic human rights, it’s a daily battle spent fighting for causes held dear, through whatever channels available.

Therein lies the question: when the odds are against us, through what other unconventional and unique means can we youths of today manifest our voices? And with our voices, how much of a difference can we truly make—whether as individuals, or as a whole—in challenging the existing order, within a shifting global landscape fraught with uncertainty?

These women no longer recognise the present Hong Kong, which has been gradually silenced by Chinese Communist authorities determined to end the city’s semi-autonomous status. Unable to return home to physically partake in pro-democracy protests, how else can these four individuals, in their personal capacities, help their motherland reclaim its lost voice?

The first step is to revisit Hong Kong’s colonial history, a process that can paradoxically only be carried out in London rather than at home, as the city does not have a public archives law that grants its citizens access to important political documents.

By sifting through and decoding Hong Kong’s archives released by the United Kingdom, the volunteers interviewed in Home, and a Distant Archive unearth how the former British colony’s past, present and future intersect in ways that few of their countrymen have been privy to, in the hopes of understanding how, and why, Hong Kong came to be the way it is today.

“If you don’t know about your past, what we have done right or wrong, how can you reposition or reshape the future?” she asks.

It’s a cogent statement that underscores the importance of translating the learnings from the city’s bygone era for—and to—the future, in order to empower successive generations of citizens to rebuild Hong Kong’s fractured identity, to help their motherland find its voice back.

At its core, Home, and a Distant Archive is a meditation on the complexities of national identity and migration among the Hong Kong diaspora. Cheung elegantly juxtaposes anecdotes from her interviewees with her own personal narration, as a London-based Hong Konger struggling to articulate her conflicted emotions about a city that she is geographically alienated from.

“I seldom think about my sentiments towards this place,” she muses.

“Even if I like it, it is hard to say out loud.”

Decoding Hong Kong’s colonial history has ultimately been an avenue for these diaspora to confront, and reconcile, a fragmented and nebulous relationship with a homeland they feel guilty for forsaking, at a time of great political upheaval.

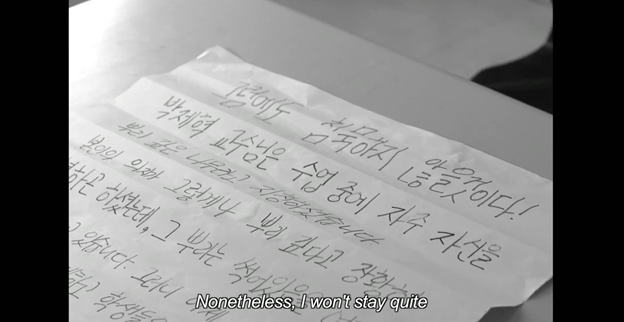

Handwritten posters—known as daejobo in South Korea—have become increasingly popular with the nation’s youths in recent years, with more using these mediums to make social and political statements about the state of contemporary Korean society. What makes daejobo all the more distinctive, is that they are typically signed off by the writers behind the original protest message.

It is this idea of personal accountability for one’s words that inhabits the central conflict in A Hand Written Poster.

Hye-ri is the president of her school’s university poster club, which aims to be a voice for the student body in protesting against unfairness. Of late, she’s been signing off and pasting posters on campus calling for the dismissal of her professor, who has been accused of embezzling school funds. After finding out that her professor has filed a lawsuit against her, Hye-ri begins to have second thoughts about attributing subsequent protest posters to her own name.

Speaking out against injustice is one thing, but A Hand Written Poster goes a step further to question audiences if we have the courage to wholeheartedly own our voices—to be accountable to the statements we promulgate—even if this responsibility comes at the price of institutional reprisal and punishment.

Shot in a 4:3 aspect ratio, the film’s close-up shots of Hye-ri articulate this internal tension, as she wrestles between directly expressing her voice to call out existing power structures that protect its perpetrators, and allowing herself to be silenced by fear of higher authority, thereby subjecting future generations of students to a continuing cycle of corruption.

While Hye-ri is presented with a choice to use her voice to speak up for a greater public cause, the protagonists in Siew-Hong Leong’s Blind Mouth (2017) are categorically denied using their voices for even the most basic interpersonal communication.

Physically and psychologically conditioned to living without their voices, the pair transcend the boundaries of verbal speech to reach out to each other via a unique conduit—by listening to tape recordings of the daughter’s propaganda-tinged history lessons, an act of shared rebellion between them. But when tragedy strikes, these instruments end up being more than just a functional communication device; instead, they could hold the key for the pair to escape a life under extreme authoritarian regime.

With Blind Mouth shot three years ago, there’s no missing Leong’s social commentary on Malaysia’s state censorship and crackdown on freedom of speech, actualised in the literal “silencing” of the characters in her film. Then, the country was still under the reign of former Prime Minister Najib Razak, who sought to prosecute activists and even ordinary citizens who expressed any form of political discontent.

But how much change can be brought about, even when systems change hands over time? Perhaps certain power structures are ingrained—despite making a free speech pledge earlier in the year, Malaysia’s new government led by Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin has since charged multiple local and international journalists for reportage deemed critical of the administration.

Every day, we weigh temporarily compromising creature comforts against the greater public good of keeping a global virus at bay; elsewhere, it’s a battle of more permanent proportions, between giving up on your community and homeland, or persisting in a unified national fight for one’s legitimate rights and freedom.

Our generation of youths may have accepted ceding a degree of control to the unknown, but we are not debilitated. It is time for us to take stock of the autonomy and agency we hold in our own remaining capacities, to speak out for the change we desire. The future remains ours to make, and take.